ARTICLE AD BOX

Image source, Getty

Image source, Getty

Simon King

Lead Weather Presenter

For eight days in April 2010 UK and European airspace was closed or partially closed causing chaos to travellers around the world.

The Eyjafjallajökull volcano in Iceland explosively erupted on14 April sending a huge ash cloud into the atmosphere and the weather pattern directed it towards Europe.

Creating the worst disruption to air travel since World War Two, it put a spotlight on how unprepared the aviation industry was for the consequences of a volcanic eruption.

Fifteen years on procedures have changed but could we see turmoil like that again?

Heathrow airport closed for a day in late March after a fire at a nearby substation cut power and resulted in 1,300 cancelled flights, with thousands of passengers affected.

It feels hard to imagine now what it was like having eight days of airspace closure across the UK and Europe in 2010 with 300 airports closed, 100,000 flights cancelled, 10 million passengers unable to travel and a reported £1.1 billion loss for the airline industry.

Image source, Getty

Image source, Getty

Flights were grounded for eight days in mid-April 2010 with a major impact on passengers in the UK and around the world

'Black Swan Event'

The day after the Eyjafjallajökull eruption which spewed ash high into the atmosphere - around 20 to 50,000ft (4-10 miles) where commercial airlines operate - that ash started to drift southward into UK airspace.

International aviation rules at the time were that aircraft could not fly into any levels of volcanic ash and the airspace was quickly closed down.

This had never caused a problem before because most volcanic eruptions up to that point were localised and airlines were able to fly around ash cloud without issue.

According to Jonathan Nicholson from the UK Civil Aviation Authority (CAA): "It was what a lot of people called a 'Black Swan Event' - unforeseen, typically with extreme consequences - but it was a Black Swan that was ultimately predictable because Icelandic volcanoes happened and will continue to happen."

Passengers were stranded around the world, scrambling to find any method of transport to get home.

"An eye opener globally"

The Met Office operates one of nine global Volcanic Ash Advisory Centres (VAAC) and is responsible for issuing advisories for volcanic eruptions originating from the north eastern corner of the North Atlantic, including Iceland.

Once Eyjafjallajökull erupted the centre ran computer models with forecast data and for Dr Matthew Hort, Head of Atmospheric Dispersion at the Met Office, it was the most intense period of his working life before and since.

He said: "It was an eye opener globally. The unique thing about the Icelandic eruption was that it happened in an area where we had winds from the north that brought the ash down across UK airspace and trans-Atlantic routes."

Image source, Met Office

Image source, Met Office

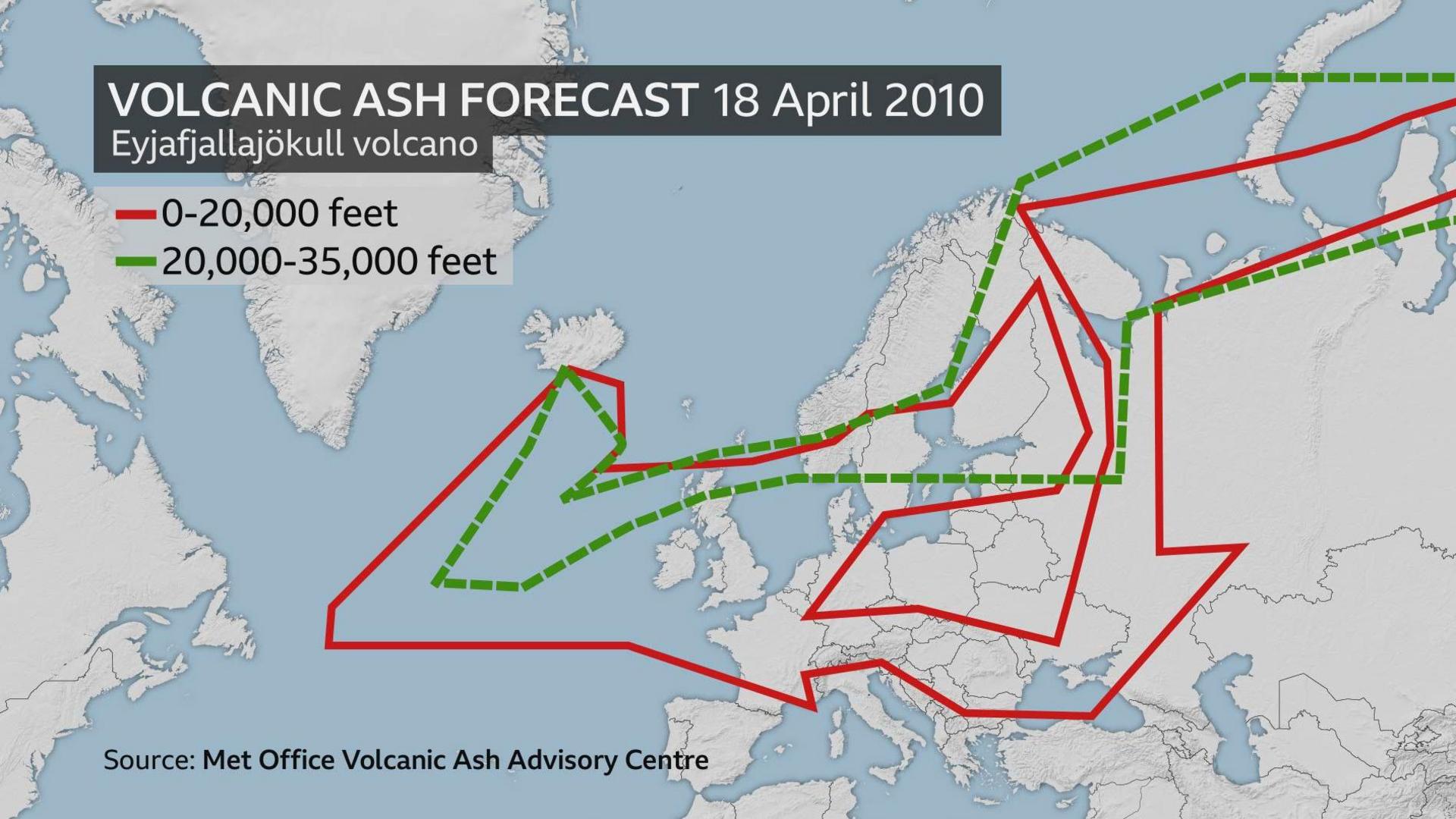

Four days after the main eruption the Met Office dispersion forecasts showed ash across the UK, the Atlantic, most of Europe and western Russia.

As the days of disruption went on with no sign of ash contamination clearing, everyone was under pressure to find a way to re-open airspace in a safe and controlled way.

Airlines and engine manufacturers had to conduct research to ascertain if there was a safe level of ash concentration which wouldn't damage jet engines.

Rolls-Royce was at the forefront of pioneering testing and for the first time was able to establish a level of volcanic ash that didn't seriously affect the jet engine over a given timeframe.

Mr Nicholson explained: "In conjunction with Met Office forecasts it enabled us to open airspace where there were low levels of ash."

On 20 April after an international teleconference headed by the CAA, it was agreed that 2 milligrams of ash per cubic metre of air was an acceptable safe ash concentration.

Airspace re-opened that night with flights operating as normal.

Eyjafjallajökull continued to erupt well into June with occasional spikes of higher ash concentration coming into the UK but under the new rules authorities were able to keep most of the airspace open with only localised airport closures.

Image source, Getty

Image source, Getty

Airlines had a 'zero volcanic ash' policy for jet engines in 2010

Have things changed?

In the months and years after research and working groups continued to assess procedures and rules.

"The work that happened very quickly at the time around the event got us to 90% of where we are now…but that has been consolidated and put into specific safety measures," Mr Nicholson said.

Today there are three levels of volcanic ash contamination - low, medium and high, with guidance on how long a pilot can fly in those concentrations before causing significant damage.

"If something similar happened today, it will be up to the airlines to use their own permissions from the engine manufacturers and their own safety cases to decide where and when, based on forecasts, will allow them to go," Mr Nicholson added.

"And that will be different for each airline as some may accept higher or lower levels of ash as acceptable."

There has also been a massive development programme in the monitoring and forecasting of volcanic ash.

As a direct result of the ash cloud the Met Office deployed permanent LIDAR instruments that point a laser into the sky capable of measuring ash concentrations.

New satellites have also been launched globally which enable scientists to monitor ash concentrations every 15 minutes.

In addition there have been advances in computer modelling to improve the physics and processes involved in how different shapes and sizes of volcanic ash behave in the atmosphere.

Image source, Getty

Image source, Getty

Volcano has been erupting intermittendly near Grindavik, Icleand with large lava flows but no ash cloud

Could it happen again?

What is clear today is that as a direct result of 2010, with all the improvements made, the UK and Europe is in a much better place to control and manage volcanic ash.

In recent months there have been small eruptions in Iceland leading to the evacuation of Grindavik and the closure of the famous Blue Lagoon spa.

However, there has been little concern to aviation as these recent eruptions are mostly small fissure eruptions with large and slow lava flows - rather than the explosive ash eruption from Eyjafjallajökull.

Experts believe that if the 2010 volcanic ash event happened today there would be "nowhere near the same level, if any, disruption" according to both Dr Hort and Mr Nicholson, largely because we now know that the level of ash seen in UK airspace in 2010 was relatively low and safe to fly in.

But Dr Hort warns: "You can always have a bigger eruption."

If a volcano erupted with really high levels of ash affecting UK or European airspace, then "absolutely we will see disruption because it's a safety issue", added Mr Nicholson.

1 day ago

1

1 day ago

1

English (US) ·

English (US) ·