ARTICLE AD BOX

SPL

SPL

Scientists can tell how ancient human populations evovled by analysing their DNA

Far from triumphantly breezing out of Africa, modern humans went extinct many times before going on to populate the world, new studies have revealed.

The new DNA research has also shed new light on the role our Neanderthal cousins played in our success.

While these early European humans were long seen as a species which we successfully dominated after leaving Africa, new studies show that only humans who interbred with Neanderthals went on to thrive, while other bloodlines died out.

In fact, Neanderthal genes may have been crucial to our success by protecting us from new diseases we hadn't previously encountered.

The research for the first time pinpoints a short period 48,000 years ago when Homo sapiens interbred with Neanderthals after leaving Africa, after which they went on to expand into the wider world.

Homo sapiens had crossed over from the African continent before this, but the new research shows these populations before the interbreeding period did not survive.

Prof Johannes Krause of the Max Planck Institute of Evolutionary Biology, in Germany, told BBC News that the history of modern humans will now have to be rewritten.

"We see modern humans as a big story of success, coming out of Africa 60,000 years ago and expanding into all ecosystems to become the most successful mammal on the planet," he said. "But early on we were not, we went extinct multiple times."

DAVID GIFFORD / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

DAVID GIFFORD / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

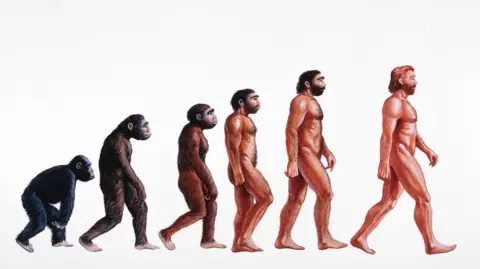

The story of our species' smooth march through evolution will have to be rewritten, says scientists

For a long time, deciphering how the only surviving species of humans evolved was based on looking at the shapes of fossilised remains of our ancestors living hundreds of thousands of years ago and observing how their anatomy subtly changed over time.

The ancient remains have been sparse and often damaged. But the ability to extract and read the genetic code from bones that are many thousands of years old has lifted a veil on our mysterious past.

The DNA in the fossils tell the story of the individuals, how they are related to each other and their migration patterns.

Even after our successful interbreeding with Neanderthals, our population of Europe wasn't without hitches.

Those first modern humans that had interbred with Neanderthals and lived alongside them died out completely in Europe 40,000 years ago - but not before their offspring had spread further out into the world.

It was the ancestors of these early international pioneers who eventually returned to Europe to populate it.

BBC News

BBC News

The research also gives a new perspective on why Neanderthals died out so soon after modern humans arrived from Africa. No one knows why this happened, but the new evidence steers us away from theories that our species hunted them out of existence, or that we were somehow physically or intellectually superior.

Instead, Prof Krause says that it supports the view that it was due to environmental factors.

"Both humans and Neanderthals go extinct in Europe at this time," he said. "If we as a successful species died out in the region then it is not a big surprise that Neanderthals, who had an even smaller population went extinct."

SPL

SPL

A Neanderthal skull. The species lived alongside us for thousands of years until they went extinct around 40,000 years ago

The climate was incredibly unstable at the time. It could switch from nearly as warm as it is today to being bitterly cold, sometimes within a person's lifetime, according to Prof Chris Stringer of the Natural History Museum in London, who is independent of the new research.

"The study shows that near the end of their time on the planet, Neanderthals were very low in numbers, less genetically diverse than the modern human counterparts they lived alongside, and it may not have taken much to tip them over the edge to extinction," he said.

A separate DNA study, published in the journal Science, shows that modern humans held on to some key genetic traits from Neanderthals that may have given them an evolutionary advantage.

One relates to their immune system. When humans emerged from Africa, they were extremely susceptible to new diseases they had never encountered. Interbreeding with Neanderthals gave their offspring protection.

"Perhaps getting Neanderthal DNA was part of the success because it gave us better adaptive capabilities outside of Africa," said Prof Stringer. "We had evolved in Africa, whereas the Neanderthals had evolved outside of Africa."

"By interbreeding with the Neanderthals we got a quick fix to our immune systems."

1 month ago

11

1 month ago

11

English (US) ·

English (US) ·