ARTICLE AD BOX

Reuters

Reuters

Debra Tice said she had "no idea" where her son was following the fall of Bashar al-Assad's regime in Syria

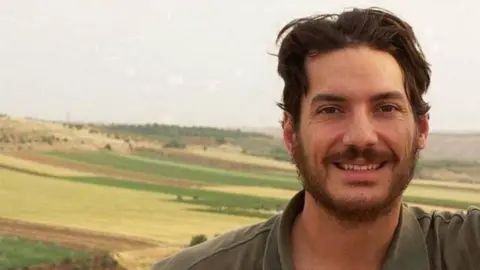

The mother of US journalist Austin Tice, abducted in Syria while on a reporting trip in 2012 and one of the longest-held American hostages, has returned to the country for the first time in a decade to renew the search for her son.

Debra Tice's visit comes in the wake of the fall of Bashar al-Assad's regime in a lighting rebel offensive last month. Her son, a freelance journalist who is now 43, was taken captive as he travelled through the Damascus suburb of Darayya covering the Syrian civil war.

"We had information, but the whole world changed," she said in an interview in the Syrian capital, Damascus, referring to Assad's removal from power.

"We have no idea where he is now. It feels a little bit like square one, trying to figure that out again."

Getty Images

Getty Images

Austin Tice was taken captive in the Damascus suburb of Darayya in 2012

Tice was last seen in a video posted online weeks after his capture, blindfolded and in apparent distress. No government or group has claimed being behind his disappearance, although over the years, US officials said they believed Tice was being held by the Assad government.

According to recent reports in US media, investigators believe that Tice, a former US Marine, briefly escaped weeks after being seized but was recaptured by forces who answered directly to Assad.

Last month, after rebels led by the Islamist group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) toppled Assad and seized power, President Joe Biden said the US believed Tice was alive, but that his whereabouts remained unknown. The rebels opened Syria's prisons, releasing thousands of people and giving experts access to documents that could shed a light on what happened to Tice and other disappeared people.

Reuters

Reuters

Debra Tice met Syria's de facto leader, Ahmed al-Sharaa, on Sunday

"I've never had a moment of doubt... I always knew that [Tice] is going to walk free. And, you know, we have a whole new way of thinking about how that's going to happen," she said. "I can hardly wait for my arms around [him]."

On Sunday, Debra Tice - who said she wore a "Free Austin Tice" badge even at home - met Ahmed al-Sharaa, the Syrian de facto leader, who has vowed to hold accountable those responsible for the most serious crimes during the Assad regime.

She said she hoped the families would continue to have access to the facilities where prisoners were held "to allow people to search and keep hope".

"I'm here to be with people that understand the longing, to be able to celebrate with people that are being reunited, and also hold the hearts of those of us that are still searching and waiting and wishing and hoping and praying."

She had visited Syria for the last time in 2015, when the country's authorities stopped issuing visas to her. Now, she said, "people are more relaxed" and "children have smiles on their faces".

"I want to be one of the moms, one of the families that finds my loved one and throbs my arms around him and takes them home," she said.

12 hours ago

2

12 hours ago

2

English (US) ·

English (US) ·