ARTICLE AD BOX

Adrienne Murray

Technology Reporter

Reporting fromLongyearbyen, Norway

Getty Images

Getty Images

Norway's Longyearbyen is the world's most northernmost town

High above the Arctic Circle, the archipelago of Svalbard lies halfway between mainland Norway and the North Pole.

Frozen, mountainous, and remote, it's home to hundreds of polar bears and a couple of sparse settlements.

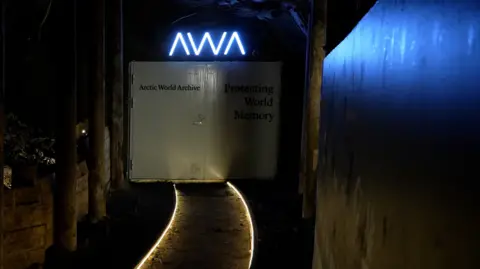

One of those is Longyearbyen, the world's northernmost town, and just outside the settlement, in a decommissioned coal mine, is The Arctic World Archive (AWA) - an underground vault for data.

Customers pay to have their data stored on film and kept in the vault, for potentially hundreds of years.

"This is a place to make sure that information survives technology obsolescence, time and ageing. That's our mission," says founder Rune Bjerkestrand, leading the way inside.

Switching on head-torches we descended a dark passageway and followed the old rail tracks 300 metres into the mountainside, until we reached the archive's metal door.

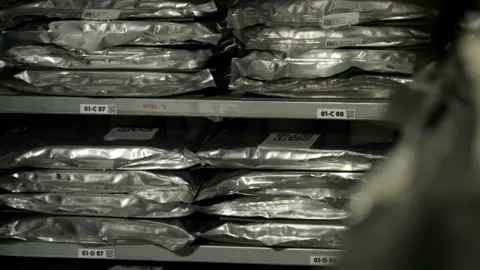

Inside the vault, stands a shipping container stacked with silver packets, each containing reels of film, on which the data is stored.

"It's a lot of memories, a lot of heritage," Mr Bjerkestrand says.

"It's anything from digitised art pieces, literature, music, motion picture, you name it."

Since the archive's launch eight years ago, more than 100 deposits have been made by institutions, companies and individuals, from 30-plus countries.

Among the many digitised artefacts are 3D scans and models of the Taj Mahal; tranches of ancient manuscripts from the Vatican Library; satellite observations of Earth from space; and Norway's treasured painting, the Scream, by Edvard Munck.

The Arctic World Archive is in an disused coal mine near Longyearbyen

The AWA is a commercial operation and relies on technology provided by Norwegian data preservation company, Piql, which Mr Bjerkestrand also heads.

It was inspired by the Global Seed Vault, a seed bank that's located only a few hundred metres away, a repository where crops can be recovered after natural or manmade disasters.

"Today, there are a lot of risks to information and data," said Mr Bjerkstand. "There is terrorism, war, cyber hackers."

According to him, Svalbard is the perfect place, for hosting a secure data storage facility.

"It's far away from everything! Far away from wars, crisis, terrorism, disasters. What could be safer!"

Underground it's dark, dry and chilly, with temperatures remaining sub-zero all year-round; conditions which Mr Bjerkestrand claims are ideal for keeping the film safe for centuries.

Should global warming cause the thick Arctic permafrost to thaw, the vault is still robust enough to preserve its contents he says.

At the back of the chamber, another large metal box contains GitHub's Code Vault.

The software developer has archived hundreds of reels of open source code here, which are the building blocks underpinning computer operating systems, software, websites and apps.

Programming languages, AI tools, and every active public repository on its platform, written by its 150 million users, are also stored here.

"It's incredibly important for humanity to secure the future of software, it's become so critical to our day to day lives," Githhub's chief operating officer, Kyle Daigle tells the BBC.

His firm has explored a variety of long-term storage solutions, he said, and there are challenges. "Some of our existing mechanisms can be stored for a very long time, but you need technology to read them."

The film is stored in metallic envelopes in the underground vault

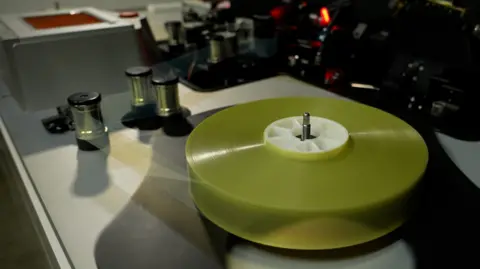

At Piql's headquarters in southern Norway, data files are encoded onto photosensitive film.

"Data is a sequence of bits and bytes," explains senior product developer, Alexey Mantsev, as film ran through a spool at his fingertips.

"We convert the sequence of the bits which come from our clients data into images. Every image [or frame] is about eight million pixels."

Once these images are exposed and developed, the processed film appears grey, but viewed more closely, it's similar to a mass of tiny QR codes.

The information can't be deleted or changed, and is easily retrievable explains Mr Mantsev.

"We can scan it back, and decode the data just the same way as reading data from a hard drive, but we will be reading data from the film."

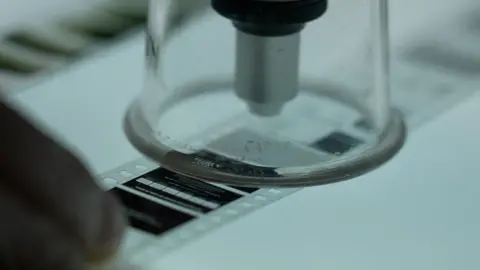

One key question arising with long-term storage methods, is whether people will understand what has been preserved and how to recover it, centuries into the future.

That's a scenario Piql has also thought about, and so a guide that can be magnified and read optically, is printed onto the film, as well.

Clients pay to have their data transferred to tape and stored in the Arctic

Every day more data is being used and generated than ever before, but experts have long warned of a potential "digital Dark Age", as technological advances render previous software and hardware obsolete.

That could mean the files and formats we use now, face a similar fate to the floppy disks and DVD drives of the past.

Many firms offer long-term data storage.

Cassettes of magnetic tape known as LTO (Linear Tape Open), are the most common form, but newer innovations promise to revolutionise how we preserve information.

For example, Microsoft's Project Silica has developed 2mm-thick panes of glass, onto which chunks of data is transferred by powerful lasers.

Meanwhile a team of scientists from the University of Southhampton have created a so-called 5D memory crystal, which has saved a record of the human genome.

That's also been placed in the Memory of Mankind repository, another vault safeguarding historic documents, hidden in a salt mine in Austria.

The film contains instructions on how to read the data

The Arctic World Archive receives deposits three times a year, and as the BBC visited, recordings of endangered languages and the manuscripts of the composer Chopin, were among the latest reels placed in the vault.

Photographer, Christian Clauwers, who's been documenting South Pacific Islands threatened by sea level rise, was also adding his work.

"I deposited footage and photography, visual witnesses of the Marshall Islands," he says.

"The highest point of the island is three meters, and they're facing huge impact of climate change."

"It was really humbling and surreal," says archivist Joanne Shortland, head of Heritage Collections at the Jaguar Daimler Heritage Trust, after depositing records, engineers' drawings and photographs of historic car models.

"I have all these formats that are becoming obsolete.

"You need to keep changing the file format and making sure that it's accessible in 20 or 30, years time. The digital world has so many problems."

More Technology of Business

10 hours ago

9

10 hours ago

9

English (US) ·

English (US) ·