ARTICLE AD BOX

Singapore Prison Service

Singapore Prison Service

A guard monitors CCTV in the Drug Rehabilitation Centre (DRC) control room

Kim* is a young professional who started using cannabis when family life became messy. Things improved, but her drug habit stuck - and by then, her social circle was primarily made up of people who also used. With a reliable local supplier of weed, Kim’s friends asked her if she would get some for them.

“That’s what I did,” Kim says. “I never marked up the price in any way, because this was friendship... It’s like, I’m helping you to purchase something we both use anyway.”

Singapore, where Kim lives, has some of the harshest drugs laws in the world.

If you sell, give, deliver, administer, transport or distribute narcotics, that’s drug trafficking. And the law also presumes you’re a trafficker if you possess drugs in quantities that cross certain weight thresholds.

Kim’s life unravelled very fast when one of the friends she sourced cannabis for was caught by the state’s Central Narcotics Bureau.

Kim was named as the supplier of the marijuana, and picked up too. After the authorities trawled through her phone, another friend was arrested - and Kim was charged with drug trafficking.

“I was wracked with horror,” she says. “To have charges of trafficking levelled at me? That was just overwhelming. I felt complete and utter fear of what was going to pan out for me.”

Cannabis for recreational use has been decriminalised in many places around the world. In the US, 24 states have legalised it. While cannabis is illegal In the UK, punishments for its possession have plummeted in recent years.

In Singapore, if you’re found with 15g you’re assumed to be trafficking - and with 500g or more, the death penalty is mandatory.

It’s a controversial policy and there have been several recent cases. The most recent execution - of a 64-year-old on a heroin charge - took place on 16 October.

The Singaporean government won’t tell the BBC how many people are currently on death row.

Singapore’s death penalty becomes mandatory in drug cases involving

- 15g diamorphine (heroin)

- 30g cocaine

- 500g cannabis

- 250g methamphetamine

Kim’s not facing execution, but she could be looking at a lengthy prison term.

“The minimum sentence would be five years,” she says. “The worst-case could be up to 20 years.”

While Kim awaits judgement on trafficking charges, her friends have already been dealt with. But they weren’t prosecuted. Classed as drug consumers - not traffickers - they faced very different treatment.

They were sent to the state-run Drug Rehabilitation Centre for six months each.

When anyone’s caught using an illicit substance in Singapore, they’re assessed as low, medium or high risk. Only those deemed at low risk of reoffending are allowed to stay at home, where they are monitored in the community.

Everyone else - even a first-time offender - is sent for compulsory rehabilitation.

Singapore Prison Service

Singapore Prison Service

The BBC was given rare access inside Singapore's austere Drug Rehabilitation Centre

There’s no private, residential rehab in Singapore - no mooching around in fluffy bathrobes and then retreating to your own en-suite room.

The Drug Rehabilitation Centre (DRC) is a vast complex run by Singapore’s Prison Service, which makes sense because this is incarceration by any other name. There’s barbed wire, a control room, and CCTV everywhere. Guards patrol the walkways.

In December 2023, 3,981 Singaporeans were inmates - about 1 in 8 of them women.

Institution S1 houses around 500 identically-dressed male inmates, most first or second-time drug offenders.

A cell accommodates seven or eight men. There are two toilets, and a shower behind a waist-high wall. There are no beds. The men sleep on thin, rush mats on the concrete floor. And a detainee will spend at least six months here - even if they’re a casual, rather than addicted, drug user.

“While it is rehabilitation, it’s still a very deterrent regime,” says Supt Ravin Singh. “We don’t want to make your stay too comfortable.”

Singapore Prison Service

Singapore Prison Service

Inmates are given items including a T-shirt and socks, and a rush mat on which to sleep

The men spend up to six hours a day in a classroom on psychology-based courses.

“The aim is to motivate inmates to want to stay away from drugs, to renew their lives without them, and to address negative thinking regarding drugs,” says Lau Kuan Mei, Deputy Director for the Correctional Rehabilitation Service.

Singapore Prison Service

Singapore Prison Service

Inmates take part in sessions including on mindfulness, during which they are taught how to control runaway thoughts

“They teach us a lot about how to manage our triggers for using drugs,” says Jon*, who’s in his late 20s and close to the end of a six-month stay.

Jon has a history of using methamphetamine and is one of the inmates prison authorities have selected to talk to the BBC.

Meth (also known as crystal or ice) is a powerful, highly addictive stimulant, and the most commonly abused drug in Singapore and the region.

Earlier this year, on a weekday afternoon, Central Narcotics Bureau officers arrived at Jon's house where he lives with his parents. Before they took him away, he spoke to his shocked mother.

“She said, ‘learn your lesson, pay your dues, and come back clean,” Jon remembers.

And that’s what he’s aiming to do - but he knows it won’t be easy.

“It’s exciting leaving,” he says. “But I’m also nervous... In here you’re locked up and not faced with drugs.”

Jon’s worried he might be tempted to take meth again. His rehab programme has been obligatory, not voluntary as it might have been if he lived in North America or Europe. Even so, it might not impact his chances of staying drug-free.

"If you look at evidence-based policies in drug addiction... it doesn’t really matter whether the treatment offered is voluntary or non-voluntary,” says Dr Muni Winslow, an addiction psychiatrist who worked in Singapore’s government institutions.

He believes the treatment offered to drug users has improved.

“It’s much better now because the whole criminal justice system has a lot of psychologists and counsellors who are trained in addictions.”

Historically, drugs have been viewed as a criminal justice issue, rather than a health issue in Singapore.

While the state execution of traffickers still sets the tone for how the government and most Singaporeans view narcotics, it hasn’t prevented changes to how drug users are treated. For example, no-one who spends time in the rehab centre gets a criminal record.

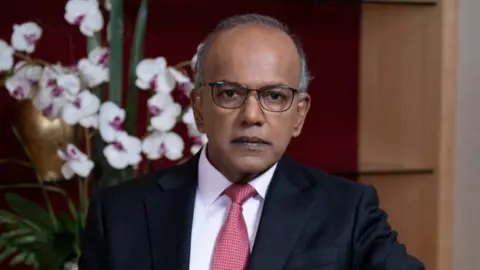

“We talked to psychologists and addiction specialists and our thinking evolved,” explains Minister for Home Affairs and Law, K Shanmugam. “If they’re not a threat to society, we don’t need to treat them as criminals.”

Home Affairs and Law Minister K Shanmugam suggests thinking on how to treat drug users has shifted in Singapore

Singapore commits huge resources to enabling people to stay clean once they leave the DRC. Most importantly, they’re helped to find work.

But although authorities say the system has changed, critics believe it's still humane.

The Transformative Justice Collective, a group which campaigns against the death penalty, describes the DRC as a form of mandatory detention where prisoners face "humiliation" and "loss of liberties".

The group says programmes in the centre are superficial and focused on "shame" - failing to tackle the root causes of drug dependence.

"We've seen a lot of lives disrupted and a lot of trauma inflicted from being arrested, from being thrown into prison, from having to share a cell," says Kirsten Han.

"It causes a lot of stress and instability. And these are not harms caused by drugs. These are harms caused by the war on drugs."

Singapore Prison Service

Singapore Prison Service

Urine testing cubicles are the first of their kind in the world

Surveillance remains a critical part of the country's mission to keep former inmates clean.

At a supervision centre, a neat-looking man in his 50s arrives. He’s been in and out of the Drug Rehabilitation Centre six times, struggling with heroin. But for the last 26 months he’s been drug-free, living at home, monitored by an electronic tag. Now his sentence is over.

When the tag’s snipped off, he’s delighted, and leaves quickly after exchanging a few words with Karen Lee, the director of the Community Corrections Command.

“He looks healthy,” she says. “And that’s what we hope for all our supervisees… While three out of 10 do come back as repeat drug abusers, we shouldn’t forget there are seven supervisees out there, successfully living their lives as reintegrated citizens of Singapore.”

While tagged, the ex-heroin user had another incentive to stay clean: regular urine analysis. Singapore’s state-of-the-art Urine Supervision Cubicles are the first of their kind in the world.

Once a supervisee enters a cubicle, the door locks behind him. After he pees into the urinal the technology tests for drugs including cannabis, cocaine, ecstasy and heroin. It takes about seven minutes.

“It’s not so boring - we’ve also prepared videos for him to watch, like Mr Bean!” says Karen Lee.

If the test is negative, a green light goes on, and the man’s free to go. A red light indicates a positive test result - and the supervisee will be re-arrested.

Singapore’s zero-tolerance policy doesn’t distinguish between casual drug users and those with an addiction. And although punishment is no longer front and centre of the system, Singapore retains draconian practices - including a legal requirement for doctors to report patients to the authorities if they disclose use of narcotics. This may well deter people from getting help with problematic drug dependency.

But the harshest treatment is reserved for those convicted of trafficking. Kim - who sourced cannabis for her friends - is trying to keep busy while she waits for the court’s decision about the charges against her.

“Once I heard there was very little possibility of me not serving a sentence, I took some time,” Kim says, “to mourn almost, for the period of my life I would lose. I think I've accepted prison on a deeper level. It just never gets easier as the day draws nearer.”

If Kim’s incarcerated - as she expects - she won’t be unusual. In December 2023, around half of the country’s convicted prison population - 2,299 people - were serving time for drug offences.

* All names have been changed.

Singapore: Drugs, rehab, execution

The laws against illegal narcotics are notoriously severe in Singapore. Penalties for trafficking include the death penalty, but the government argues its zero-tolerance policy is effective.

If you are caught using any illicit narcotic, including cannabis, you may find yourself in compulsory rehab. The BBC's Linda Pressly approached Singapore's authorities and was granted access to the state’s austere Drug Rehabilitation Centre.

She speaks to drug users who have to spend months at the facility before being released back into the community under surveillance.

3 weeks ago

9

3 weeks ago

9

English (US)

English (US)