ARTICLE AD BOX

By Secunder Kermani

BBC News, Kabul

"If you are brave no-one can stop you," says one girl in the class

Hidden away in a residential neighbourhood is one of Afghanistan's new "secret" schools - a small but powerful act of defiance against the Taliban.

Around a dozen teenage girls are attending a maths class.

"We know about the threats and we worry about them," the sole teacher tells us, but she adds, girls' education is worth "any risk".

In all but a handful of provinces in the country, girls' secondary schools have been ordered to remain closed by the Taliban.

At the school we visit, they've done an impressive job trying to replicate a real classroom, with rows of neat blue and white desks.

"We do our best to do this secretly," says the female teacher, "but even if they arrest me, they beat me, it's worth it."

Girls arrived at secondary schools in March only to be told they would be shut once more

Back in March, it seemed as if girls' schools were about to reopen. But just an hour or so after pupils began arriving, the Taliban leadership announced a sudden change in policy.

For the students at the secret school, and many other teenage girls, the pain is still raw.

"It's been two months now, and still schools haven't reopened," one 19-year-old in the makeshift classroom told us. "It makes me so sad," she added, covering her face with the palms of her hands to hold back the tears.

But there's also a mood of defiance.

Another 15-year-old student wanted to send a message to other girls in Afghanistan: "Be brave, if you are brave no-one can stop you."

Primary schools for girls have reopened under the Taliban, and have in fact seen a rise in attendance following the improvement in security in rural parts of the country, but it's not clear when or if older girls will be allowed back into class.

The Taliban have said the correct "Islamic environment" needs to be created first, though given schools were already segregated by gender, no-one seems sure what that means.

Taliban officials have repeatedly insisted in public that girls schools will reopen, but also admit that female education is a "sensitive" issue for them. During their previous stint in power in the 1990s, all girls were prevented from going to school, ostensibly due to "security concerns".

Now, multiple sources told the BBC, a handful of hardline but highly influential individuals in the group appear to still be opposed to it.

In private, other Taliban members have expressed their disappointment at the decision not to open girls' schools. The Taliban's Ministry of Education seemed as surprised as anyone when the leadership overruled their plans in March, and some senior Taliban officials are understood to be educating their daughters in Qatar or Pakistan.

In recent weeks, a number of religious scholars with links to the Taliban have issued fatwas, or religious decrees supporting girls' right to learn.

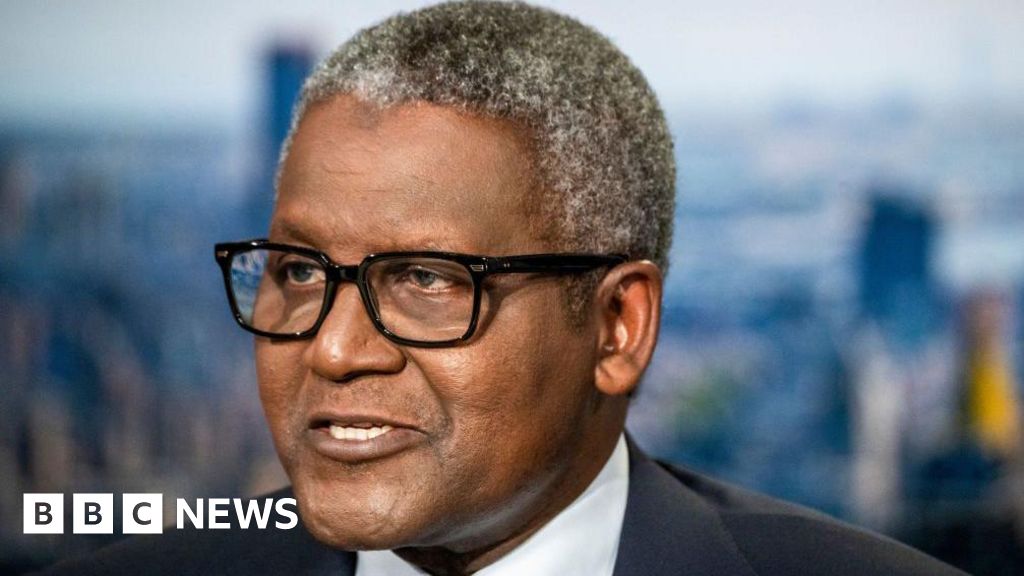

Sheikh Rahimullah Haqqani is an Afghan cleric, based largely across the border in Peshawar, Pakistan. He's well-respected by the Taliban and on a trip to Kabul last month met senior figures within their government.

Influential cleric Sheikh Rahimullah Haqqani was in Kabul last month to meet senior Taliban figures

He's careful not to criticise the continued closure of schools but, speaking at his madrassa in Peshawar, with his mobile phone in hand, scrolls through the text of his "fatwa", which shares decrees from earlier scholars and accounts from the life of the Prophet Muhammad.

"There is no justification in the sharia [law] to say female education is not allowed. No justification at all," he tells the BBC.

"All the religious books have stated female education is permissible and obligatory, because, for example, if a woman gets sick, in an Islamic environment like Afghanistan or Pakistan, and needs treatment, it's much better if she's treated by a female doctor."

Similar fatwas have been issued by clerics in Herat and Paktia provinces in Afghanistan. It's a symbol of how widespread support for girls' education now is in the country, even amongst conservative circles, but it's not clear how much of an impact the decrees will have.

The Taliban have formed a committee to examine the issue, but multiple sources with links to the Taliban told the BBC that while even senior Taliban ministers were on board with the reopening of girls schools in March, opposition to it centred around the group's leadership in the southern city of Kandahar, where the "Amir" or Supreme Leader, Mullah Haibatullah is based.

After initially adopting a more flexible attitude when taking power last August, the Taliban have recently been issuing more and more hardline edicts, including making the face veil compulsory for women and encouraging them to stay at home.

The Taliban ruled this month that women in Afghanistan must wear a face veil

Meanwhile, their tolerance for dissent, even in their own ranks, is dissipating.

One Taliban member with a large following on social media, had tweeted critically about the closure of girls' schools, as well as new rules ordering government employees to grow their beards. However, according to one source, he was called in for questioning by the Taliban intelligence department, later deleting his tweets and apologising for his earlier comments on beards.

There appears to be very little grassroots opposition to female education in Afghanistan, but some Taliban figures cite concerns about the Islamic State group using the issue as a recruitment tool, if girls' schools are opened up.

Western officials, however, have also made clear that progress on women's rights is key for the Taliban to be able to access some of the billions of dollars of foreign reserves that are frozen.

Women in Afghanistan face an uncertain future following the Taliban's takeover

Meanwhile, Afghan women's rights activists are trying to ensure a generation of girls aren't left behind.

At the secret school we visited, they hold lessons for one or two hours per day, focused on maths, biology, chemistry and physics.

The teacher in charge knows there are many other girls who would like to attend, but they're constrained by the lack of space and resources, as well as the need to remain below the radar.

She's not hopeful about the prospect of regular schools opening up any time soon, but is determined to do what she can.

"As an educated woman, it's my duty," she tells the BBC. "Education can save us from this darkness."

2 years ago

39

2 years ago

39

English (US)

English (US)