ARTICLE AD BOX

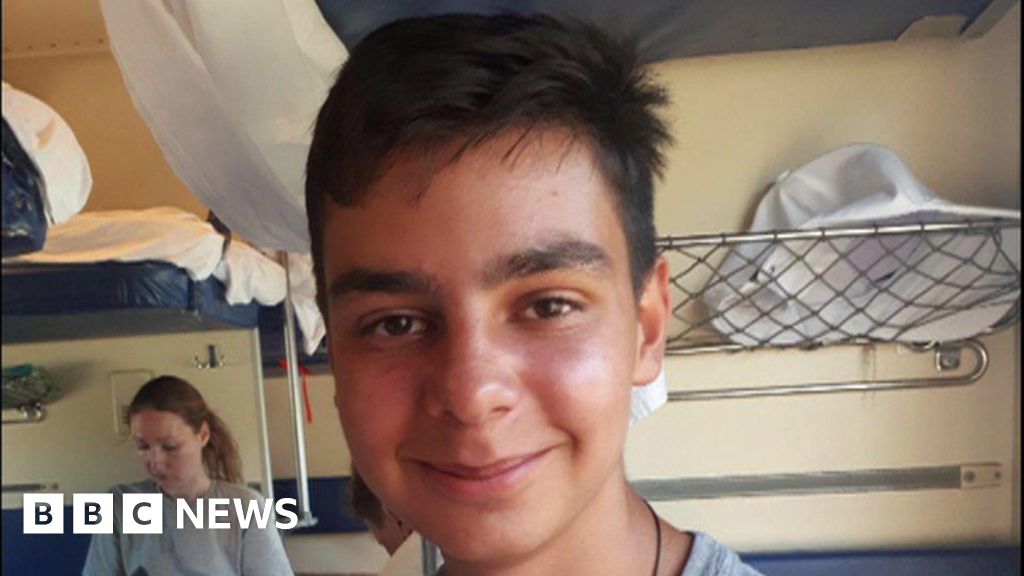

Mohamed Omar says he travelled the world as a flight attendant but lost his job when the Taliban returned to power

By Yalda Hakim

BBC News, Kabul

"I was under the bridge trying to get some drugs when I felt a hand grab me from behind. It was the Taliban. They had come to take us away."

Mohamed Omar recalls the moment Taliban soldiers showed up unexpectedly at the Pul-e-Sukhta bridge in western Kabul.

Long before the hardline Islamist group returned to power in August 2021, the area was a notorious hangout for drug addicts.

In recent months, the Taliban have been rounding up hundreds of men across the capital - from the bridge, from parks and from the hilltops. Most have been taken to a former US military base, which has been turned into a makeshift rehabilitation centre.

Afghanistan is the drug addiction capital of the world. An estimated 3.5 million people - in a country with a population of about 40 million - are addicted, according to the Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement.

Under the Pul-e-Sukhta bridge, hundreds of men can often be seen squatting - hunched among piles of rubbish, syringes, faeces and occasionally the corpses of those who had overdosed.

The drugs of choice are heroin or methamphetamine.

Image source, Getty Images

Image caption,Hundreds of mainly heroin users gather in squalid conditions beneath the Pul-e-Sukhta bridge in Kabul

The stench beneath the bridge is overwhelming, with dogs rummaging through piles of litter, looking for scraps of food. Overhead, traffic flows, street vendors hawk goods, and commuters rush to catch buses at the local depot.

"I would go there to meet my friends and take some drugs. I didn't fear death. Death is in God's hands anyway," says Omar.

The men who called this place home were mostly forgotten, despite the previous government's policy of rounding up addicts and placing them in centres. But when the Taliban retook control of the country, they launched a more aggressive campaign to remove them from the streets.

"They used pipes to whip and beat us," says Omar. "I broke my finger because I didn't want to leave the bridge and I resisted. They still forced us out."

Omar was shoved onto a bus, alongside dozens of others.

Footage later released by the Taliban government showed their soldiers clearing the area of addicts who had died from an overdose - their lifeless bodies being carried away wrapped in dark grey shawls. Others, still living, had to be taken out on stretchers because they were unconscious.

Hundreds of drug users live on streets surrounded by rubbish

The rehabilitation hospital where Omar was taken has 1,000 beds and currently 3,000 patients. Conditions are squalid. The men are kept in the centre for roughly 45 days where they undergo an intense programme before being released.

There is no certainty that these patients will not relapse.

While those removed from the streets are overwhelmingly men, some women and children have also been taken to dedicated rehabilitation centres.

Omar, like the rest of the addicts in the room at the centre in Kabul, is severely emaciated, his brown garment - provided by the authorities - loosely hanging off him, and his face gaunt.

Sitting on the edge of the bed, he describes the life he once had.

"One day I was in Dubai, the next Turkey and sometimes Iran. I travelled the world as a flight attendant with Kam Air and would often have VIP guests like the former presidents on the aircraft."

He lost his job when Kabul fell. Facing economic hardship and an uncertain future, he turned to drugs.

When the Taliban were in power in the 1990s, they all but stamped out poppy cultivation. But the drugs trade became a major source of income for them throughout their 20-year insurgency.

Now the Taliban say they have ordered an end to the poppy trade and are trying to enforce this policy. But according to the UN, cultivation increased by 32% in 2022 compared to 2021.

Meanwhile, Afghanistan's economy is on the brink of collapse, suffering from a loss of international support, security challenges, climate-related issues and global food inflation.

There are more patients than beds at the makeshift rehabilitation centre where Omar was taken

Since coming to the rehabilitation centre, Omar has become determined to get better.

"I want to get married, have a family and live a normal life," he says. "These doctors are so kind. They are trying their best to help us."

For the doctors at the centre, this is a rudimentary operation. The Taliban continue to deliver more people and the staff are struggling to find space for them.

"We need help. The international community left and cut off their assistance. But our problems have not gone away," one doctor tells me.

"There are many professionals among this group. Smart, educated people who once had good lives. But the difficulties in our society, the poverty and lack of jobs mean they were looking for an escape."

Despite the overcrowding and lack of resources, the doctors remain committed to doing everything they can to help these addicts.

"There is no certainty that these patients won't relapse once they leave. But we need to keep trying and most importantly, we need to give them hope for the future. Right now, there is none."

1 year ago

16

1 year ago

16

English (US)

English (US)