ARTICLE AD BOX

By Secunder Kermani

BBC News, Kabul

The Taliban say many women around the country obey their dress code

At the Lycee Mariam market in Kabul, known for its long row of stalls selling women's clothing, news of the Taliban's latest decree had not yet filtered down by the afternoon.

Some of those browsing the shops wore the all-encompassing blue burka that the Taliban enforced during their first stint in power in the 1990s. Others, however, had scarves covering their hair, but their faces uncovered.

"Even when you go on pilgrimage to Saudi Arabia you don't have to cover your face," one pointed out.

"Humans are born free, no-one has the right to talk about women's clothes," said Fatima, a fashionably dressed university student with sunglasses perched on her head.

Afghanistan is a deeply conservative country, and many women do wear the burka, but in bigger cities it's also common to see women wearing the simple headscarf.

After taking power last August, the Taliban had held off issuing new laws on what women should wear - until Saturday.

At a press conference, the Ministry for the Prevention of Vice and Promotion of Virtue announced that all women would have cover their face in public, and laid out an escalating set of punishments for anyone refusing to comply.

The punishment starts with a woman's male guardian (normally father, brother or husband) being visited at home by Taliban officials. Then, if a woman's appearance was still not deemed acceptable, her male relative would be summoned to see ministry officials, and after that he could even potentially be jailed for three days or sent to court.

Akif Muhajir, spokesman for the ministry, told the BBC the order was based on the Quran and the life of the Prophet Muhammad.

Other Muslims dispute the interpretation, but Akif Muhajir described the face covering as a "compulsory" part of the religion. Only 1% of Afghan women, he insisted, were not already complying with the group's understanding of how they should dress. "This is not only the order of the Islamic Emirate," he added, "but the order of Allah."

Most Muslims around the world do not consider covering the face to be a mandatory part of the religion, and, after seizing control of the country, the Taliban initially appeared to be adopting a more flexible attitude to governance.

In recent weeks, however, they have been introducing more hardline measures, many of them governing women's everyday lives - for example, assigning separate days for them to visit public parks to men, and barring them from undertaking longer distance journeys without a male guardian.

Teenage girls have still not been allowed back to school in most of the country, and whilst women are working in some sectors such as healthcare and education, many others have been told not to return to their offices.

Western diplomats have indicated that resuming development funding for the country - currently struggling with a dire economic crisis - is contingent on the Taliban's treatment of women.

When announcing this latest decree at the press conference, however, one cleric said the Taliban could never be pressured by the West into compromising on their beliefs.

Women in Afghanistan face an uncertain future following the Taliban's takeover

For Afghan women's rights activists, who have spent years struggling to make fragile progress in the country, it seems as if two decades of achievements are being rolled back.

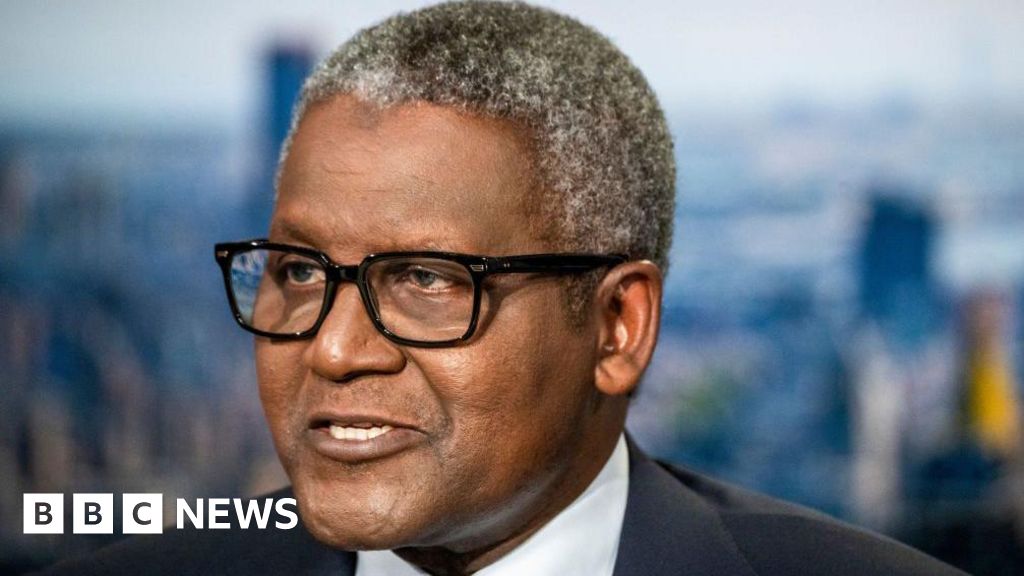

Mahbouba Seraj is one of Afghanistan's most prominent campaigners.

"We have a million other problems. Women are not a problem!" she told the BBC indignantly at her home in Kabul.

"Schools need to be opened, work needs to be given to families. There is famine all over this country. There are suicide bombings."

But, she added, despondently, "instead of looking after that, they are always after women".

Additional reporting by Malik Mudassir, Muhammad Shoaib and Mahfouz Zubaide

2 years ago

32

2 years ago

32

English (US)

English (US)