ARTICLE AD BOX

Getty Images

Getty Images

For the first time, an Algerian author has won France’s top literary award, the Goncourt, with a searing account of his country’s 1990s civil war.

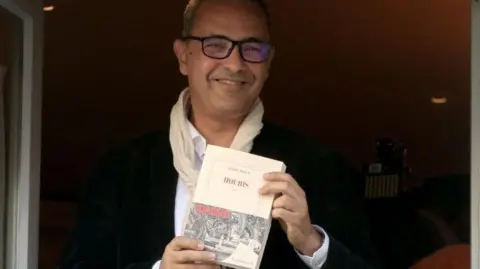

Kamel Daoud’s novel Houris tells of Algeria’s blood-soaked “dark decade”, in which up to 200,000 people are estimated to have been killed in massacres blamed on Islamists or the army.

The heroine Fajr (Dawn in Arabic) has survived having her throat cut by Islamist fighters - she has a smile-like scar on her neck and needs a speaking tube to communicate - and tells her story to the baby girl she carries inside her.

Written in French, the book “gives voice to the suffering of a dark period in Algeria, particularly the suffering of women,” the Goncourt committee said.

“It shows how literature… can trace another path for memory, next to the historical account.”

The irony is that few in Algeria are likely to read it. The book has no Algerian publisher; the French publisher Gallimard has been excluded from the Algiers Book Fair, and news of Daoud’s Goncourt success has - a day on - still not been reported in the Algerian media.

Worse, Daoud - who now lives in Paris - could even face criminal charges for speaking of the civil war.

A 2005 “reconciliation” law makes it a crime punishable by jail to “instrumentalise the wounds of the national tragedy”.

According to Daoud, the effect is to make the civil war - which traumatised the entire country - a non-subject.

“My 14 year-old daughter did not believe me when I told her about what had happened, because the war is not taught in schools,” Daoud told Le Monde newspaper.

“I cut out some of the worst scenes I wrote. Not because they were untrue, but because people would not believe me.”

Daoud, 54, had first-hand experience of the massacres because he was a journalist at the time working for the Quotidien d’Oran newspaper. In interviews he has described the ghastly routine of counting corpses, then seeing his count altered - up or down - by the authorities, depending on the message they wanted to be given.

“You develop a routine,” he said. “Come back, write your piece, then get drunk.”

Getty Images

Getty Images

Daoud's enemies in Algeria see him as a traitor but others regard him as a genius who should be celebrated

He worked as a columnist for many years, but gradually fell foul of the Algerian government because of his refusal to toe the line.

He is strongly critical of what he sees as the official “instrumentalisation” of the 1954-1962 war of independence against France; and of what he sees as the continuing subjugation of women in Algerian society.

“In a way the Islamists lost the civil war militarily, but they won politically,” he said.

“What I hope is that my book will make people think about the price of freedom, especially for women. And in Algeria, that it will encourage people to confront all of our history, not fetishise one part over the rest.”

Daoud has written two previous novels, one of which - the much-praised Meursault Investigation - was a rewriting of Albert Camus’s The Stranger and was shortlisted for the Goncourt in 2015.

In 2020 the author moved to Paris, “exiled by the force of things”, and took French nationality. “All Algerians are Franco-Algerians,” he has said. “Either out of hate or out of love.”

In Algeria he is a divisive figure. His enemies regard him as a traitor who sold his soul to France, while others recognise him as a literary genius of whom the country should be proud.

In his post-award press conference, Daoud himself said that it was only by coming to France that he was able to write Houris.

“France gave me the freedom to write. It is a land of refuge for writers,” he said. “To write you need three things. A table, a chair and a country. I have all three.”

3 weeks ago

7

3 weeks ago

7

English (US)

English (US)