ARTICLE AD BOX

By Gordon Corera

Security correspondent

Image source, Reuters

Image caption, Scientist AQ Khan cultivated his image as the "father" of Pakistan's nuclear bombOn December 11 2003, a group of CIA and MI6 officers were about to board an unmarked plane in Libya when they were handed a stack of half a dozen brown envelopes.

The team were at the end of a clandestine mission involving tense negotiations with Libyan officials. When they opened the envelopes on board the plane, they found they had been given the final piece of evidence they needed: inside were designs for a nuclear weapon.

Those designs - as well as many of the components for an off-the-shelf nuclear programme - had been supplied by AQ Khan, who has just died aged 85.

Khan was one of the most significant figures in global security in the last half-century, his story at the heart of the battle over the world's most dangerous technology, fought between those who have it and those who want it.

Former CIA Director George Tenet described Khan as "at least as dangerous as Osama bin Laden", quite a comparison when bin Laden had been behind the September 11th attacks.

The fact AQ Khan could be described as one of the most dangerous men in the world by Western spies but also lauded as a hero in his homeland tells you much about not just the complexity of the man himself but also how the world views nuclear weapons.

AQ Khan did not come to Europe as a nuclear spy, but he would become one. He was working in the Netherlands in the 1970s just as his country began a renewed drive to build a bomb in the wake of its defeat in a 1971 war, and fearful of India's nuclear advances.

Khan was working at a European company involved in building centrifuges to enrich uranium. Enriched uranium can be used for nuclear power or, if enriched enough, for a bomb. Khan was able to simply copy the most advanced centrifuge designs and then return home. He went on to build a clandestine network, largely of European businessmen, who would supply the crucial components.

Often described as the "father" of Pakistan's nuclear bomb, in reality he was one of a number of key figures. But he carefully cultivated his own mythology which made him a national hero, seen as having secured Pakistan's safety against the threat of India.

What made Khan so significant is what else he did. He turned his network outwards from import to export, becoming a globe-trotting figure and doing deals with a range of countries, many of which the West considered "rogue states".

Iran's centrifuge programme at Natanz, the source of intense global diplomacy in recent years, was built in significant part on designs and material first supplied by AQ Khan. At one meeting Khan's representatives basically offered a menu with a price-list attached from which the Iranians could order.

Khan also made more than a dozen visits to North Korea where nuclear technology was believed to have been exchanged for expertise on missile technology.

With these deals, one of the key mysteries has always been the extent to which Khan was acting alone or under the orders of his government. Particularly with the North Korean deal, all the signs are the leadership were not just aware but closely involved.

Sometimes it was suggested that Khan was simply after money. It was not so simple. As well as working closely with his country's leadership, he wanted to break the Western monopoly on nuclear weapons. Why should some countries be allowed to keep the weapons for their security and not others, he questioned, criticising what he saw as Western hypocrisy. "I am not a madman or a nut," he once said. "They dislike me and accuse me of all kinds of unsubstantiated and fabricated lies because I disturbed all their strategic plans."

Image source, AFP via Getty Images

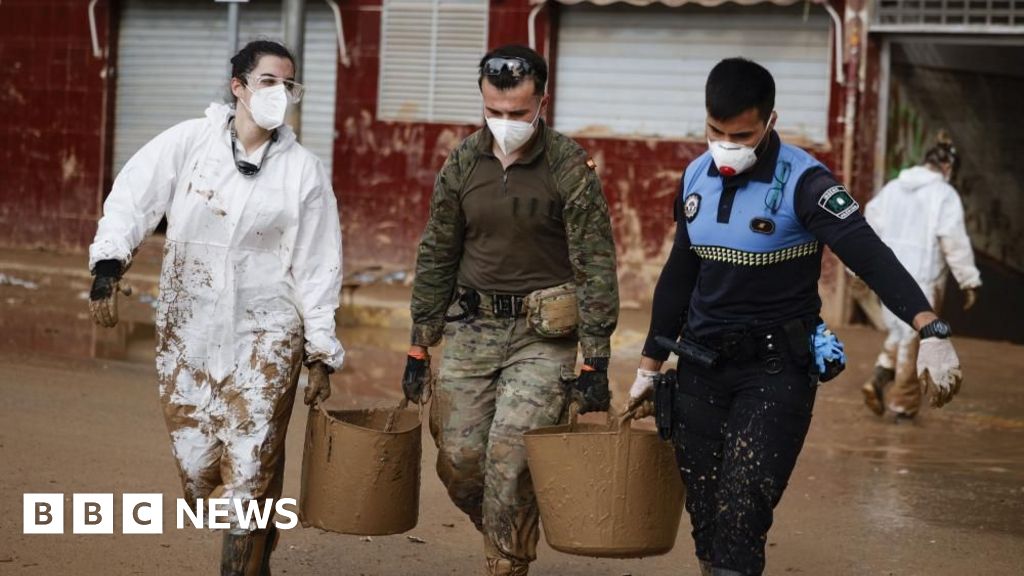

Image caption, Soldiers hold Khan's flag-draped coffin during his funeralOthers in his network, some of whom I met when writing a book about Khan, seemed more in it for the cash. The Libyan deal, brokered in the 1990s, offered rewards but also hastened their downfall.

Britain's MI6 and America's CIA had begun tracking Khan. They watched his travels, intercepted his phone calls and penetrated his network, offering vast amounts of money (at least a million dollars in some cases) to get members to become their agents and betray secrets. "We were inside his residence, inside his facilities, inside his rooms," a CIA official would say. After the September 11th 2001 attacks, fears that terrorists could get hold of weapons of mass destruction intensified, and so did the complexity of dealing with Pakistan and persuading it to act against Khan.

In March 2003, just as the US and UK were invading Iraq over weapons of mass destruction which turned out not to exist, Libyan leader Colonel Gaddafi decided he needed to get rid of his programme. That would lead to the secret visit from the CIA and MI6 team, and soon after a public announcement of a deal. That would provide the crucial leverage for Washington to push Pakistan to take action against Khan.

Khan was placed under house arrest and even forced to make a televised confession. He would live out his remaining years in a strange nether-world, neither free nor really confined. Still lauded as a hero by the Pakistani public for bringing them the bomb, but stopped from travelling or talking to the outside world. And so the full story of what he did - and why - may never be known.

3 years ago

87

3 years ago

87

English (US)

English (US)