ARTICLE AD BOX

Image source, Museum of London

Image source, Museum of London

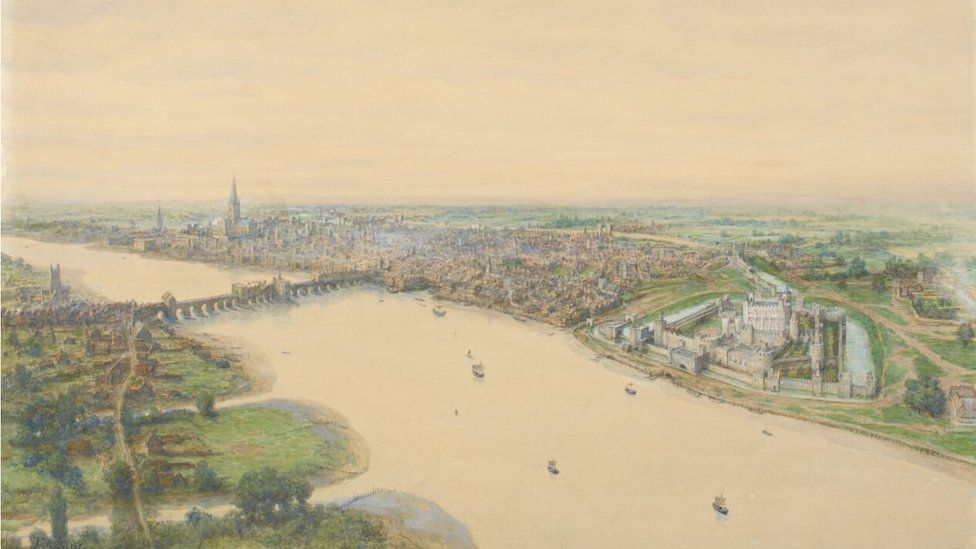

London in 1400 by Amédée Forestier, a French artist who specialised in historical landscapes

Black women of African descent were more likely to die of the medieval plague in London, academics at the Museum of London have found.

The study is the first archaeological exploration showing how racism influenced a person's risk of death during what was known as the Great Pestilence or Great Mortality.

The research is based on 145 individuals from three cemeteries.

The outbreak is believed to have claimed the lives of 35,000 Londoners.

Data on bone and dental changes of the 145 individuals from East Smithfield emergency plague cemetery, St Mary Graces and St Mary Spital formed the basis of the study.

It found there were significantly higher proportions of people of colour and those of Black African descent in plague burials compared to non-plague burials.

The likelihood of dying from the Great Pestilence was highest amongst those who already faced significant hardship, including exposure to famines that hit England during this time.

The research concluded that higher death rates amongst people of colour and those of black African descent was a result of the "devastating effects" of "premodern structural racism" in the medieval world.

What was the medieval plague?

Often referred to today as the Black Death, the outbreak of 1348-1350 was a deadly infectious disease that swept across Asia and Europe, killing millions of people.

Modern scientific research has identified this as a plague pandemic but in the mid-1300s people had no idea what the disease was or how to stop it.

It arrived in London in the autumn of 1348 and lasted until the spring of 1350.

More than half the population of London died. Emergency cemeteries had to be set up to bury them.

The disease was carried by rats who had infected fleas, and also transmitted by droplet infection, such as people coughing on each other.

Symptoms included fever, fatigue, vomiting and buboes (large swellings).

Image source, Getty Images

Image caption,A demolition labourer with a coffin of a baby, on a site discovered in a churchyard in the City of London where victims of the plague were buried in 1348

Social and religious divisions based on origin, skin colour and appearance were present in both medieval England and Europe.

Biological anthropologist from University of Colorado, Prof Sharon DeWitte, said: "Not only does this research add to our knowledge about the biosocial factors that affected risks of mortality during medieval plague epidemics, it also shows that there is a deep history of social marginalization shaping health and vulnerability to disease in human populations."

Associate professor of anthropology at Michigan State University, Dr Joseph Hefner, said: "This research takes the deep dive into previous thinking about population diversity in medieval England based on primary sources.

"Combining bioarchaeological method and theory with forensic anthropological methods permits a more nuanced analysis of this very important data."

Dr Rebecca Redfern, from the Museum of London, said: "We have no primary written sources from people of colour and those of black African descent during the Great Pestilence of the 14th Century, so archaeological research is essential to understanding more about their lives and experiences.

"As with the recent Covid-19 pandemic, social and economic environment played a significant role in people's health and this is most likely why we find more people of colour and those of black African descent in plague burials."

Listen to the best of BBC Radio London on Sounds and follow BBC London on Facebook, X and Instagram. Send your story ideas to hello.bbclondon@bbc.co.uk

Related Internet Links

The BBC is not responsible for the content of external sites.

1 year ago

47

1 year ago

47

English (US) ·

English (US) ·