ARTICLE AD BOX

By Katy Watson

Ilha de Marajó, Pará

This week, delegates arriving in Belém's international airport are being welcomed with a lively "Boi de mascara" folkloric dance routine. In fact, the whole city is celebrating being in the spotlight, playing host to the Amazon Summit.

It also feels like a bit of a warm-up for 2025 when the city hosts COP30. These two events are a big deal for this part of Brazil - a region that often feels forgotten. Belém's well-placed too, as the capital of Pará, the most deforested state in all of Brazil.

President Lula da Silva called this summit to bring together the eight South American countries who share a slice of the Amazon.

It's the first time in 45 years that there's been a meeting like this, ensuring a regional response to combat crime and deforestation as well as climate change.

"I think the world needs to look at this meeting in Belém as a milestone," Lula told the BBC last week.

"I've participated in several meetings and many times they talk, talk, talk, approve a document and nothing happens. This meeting is the first great opportunity for people to show the world what we want to do."

President Lula da Silva has promised to reverse rising deforestation seen under his predecessor Jair Bolsonaro. In July this year, deforestation fell 66% compared with 2022 and Lula's committed to zero deforestation by 2030.

"You have no idea how much pressure there was in our community from the Bolsonaro government," says Robson Gonçalves Machado, who lives on the banks of the River Acangatá. "Landowners circling in planes, soya farmers wanting to buy the land to deforest it."

Robson lives on the banks of one of hundreds of waterways that wind their way through Ilha do Marajó. It's the world's largest river island and sits on the northern coast of Brazil near Belém - the easternmost part of the Amazon.

The only way to get to Robson's community is by boat - 13 hours overnight from Belém. It may feel isolated, but he's definitely aware of the demand there is for their land from outsiders.

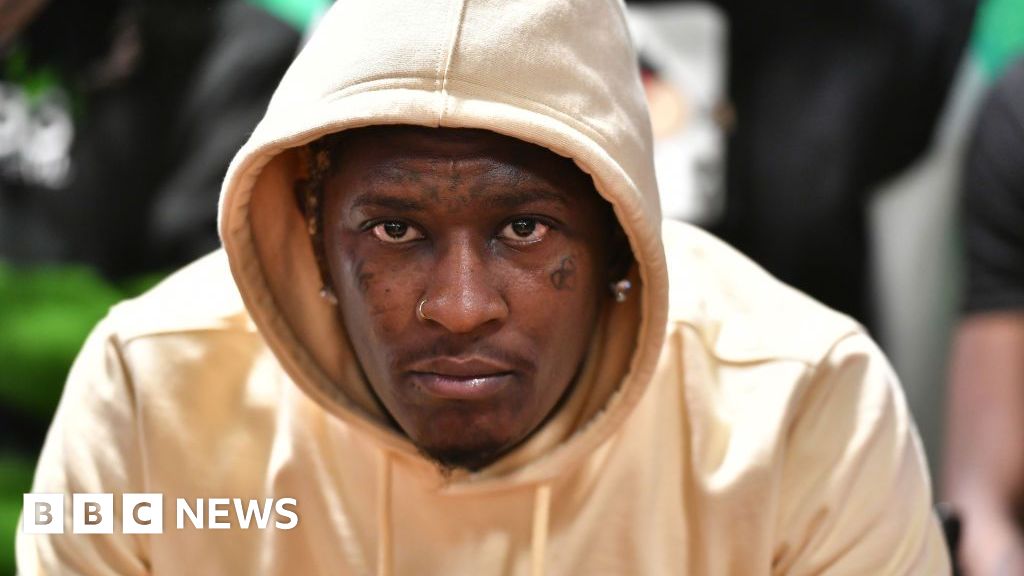

Robson Gonçalves Machado lives on the banks of the River Acangatá

While Pará is well-known as the epicentre of Brazil's deforestation, more recently it's also become an appealing prospect for another burgeoning forest industry - carbon credits.

The way it works is this: an organisation that pollutes can buy a credit which is worth one tonne of carbon dioxide - so for every tonne of CO2 emitted, the credit represents a tonne of CO2 that was captured.

Those credits are bought and sold and their prices are determined like any other market. With the World Bank estimating the carbon credit market in the forest is worth $210bn (£165bn) a year, there's huge potential.

While the summit is a diplomatic event, the run-up to the meeting included several days of discussions on issues including the carbon market.

Image source, EPA

Image caption,Indigenous people of different ethnic groups marched in Belém for land demarcation

Robson's community of Acangatá recently signed a statement of intent with one of the carbon credit companies working in the area. It's not kicked off in earnest, but they have to undertake courses that include sustainable forestry management, chicken rearing and biogas projects.

"At the beginning there were lots of doubts," says Robson. "In the municipality there was a huge land grab worth millions of reais of carbon that was sold and that didn't get passed down to the community."

Carbon credit companies operating in Ilha do Marajó have been accused of harassing people into contracts, pressuring people to be a part of their projects, without actually giving them much detail.

Pará's public prosecutor has since got involved to halt projects that have caused concern. The market still remains unregulated although Lula has promised to address this.

Teacher Bianca Teles and her family make their living from cassava flour in a community two hours boat ride from Robson. The $200 they earn a week isn't enough. When a carbon credit company offered to help build a school and health centre, even that wasn't enough to convince her.

"It's not that transparent," she said. "We can't see how it would give us a secure life. We're always on the back foot, fearing the consequences. Because of these stories we heard, we decided not to sign a contract."

Many of the problems arise because the state is so absent in the Amazon - public services are weak, people feel abandoned. And that's when companies often come in to fill that gap - for good and bad.

"When the state isn't there, it creates a no man's land where anything can happen," says prosecutor Eliane Moreira.

Janaína Dallan is CEO of Carbonext, which works on carbon capture projects

On the other side of Ilha do Marajó, Hernandez Pantoja proudly shows off his açai and cacao plantation. The machinery and training were provided for by Carbonext, a Brazilian carbon credit company that has received investment funding from Shell. The community will also get a share of the credits.

"Just last year we chucked out five illegal sawmills from our land," he says. The community knows that defending their territory from illegal logging is a challenge on their own. But partnering with a company with the funds behind it, and a plan to ensure sustainable forestry, is the only way forward. "We want support to look after our forest - we don't want to cut down trees anymore."

For Carbonext, empowering the communities to look after their land is important. So too is empowering the region as a whole.

"When the global north comes to the global south and says, 'I have the solution,' we're like, 'Really? Have you been to the Amazon?'" says CEO Janaína Dallan. "How can you solve that problem if you've never been there? You don't have your boots on the ground. So it's very easy to say, 'I have the solution.'"

People on the ground in the Amazon - and those at the summit this week - are determined to make South America's voice heard when it comes to climate change.

1 year ago

29

1 year ago

29

English (US)

English (US)