ARTICLE AD BOX

Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty Images

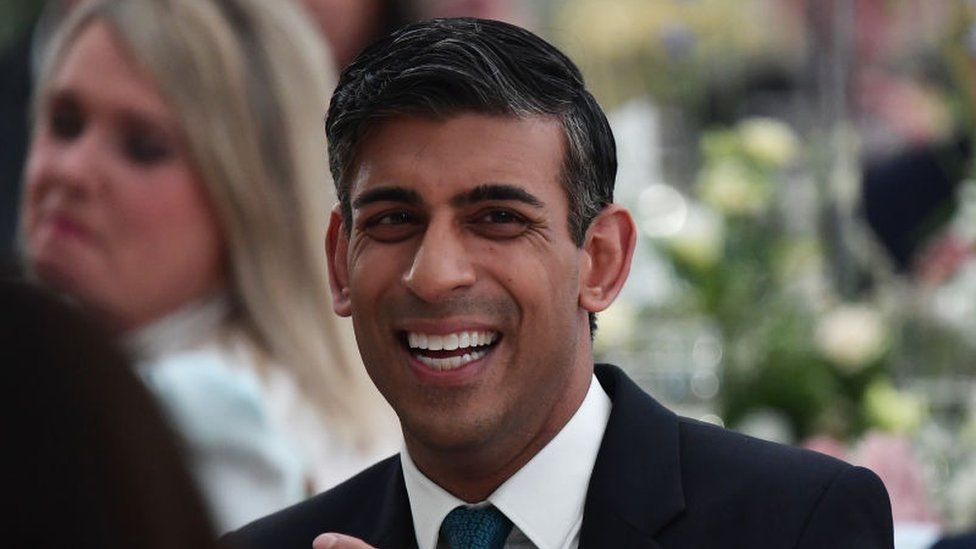

Rishi Sunak visited Northern Ireland last year, to mark the 25th anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement

By Chris Mason

Political editor, BBC News

Like the two sets of parents at a wedding, the British and Irish prime ministers are in Belfast today.

The analogy works, just about, I think, because London and Dublin are co-guarantors of the Good Friday Agreement, the deal signed nearly 26 years ago which provides the foundation for power-sharing devolved government in Northern Ireland.

And, like many a family argument, I detect a splash of irritation in Whitehall that the Irish government is, I hear whispered, muscling in on a moment they think belongs to the prime minister.

After two years of political stasis here, devolved government is up and running again.

Just over four years ago, when Stormont was again revived - after a three-year gap that time - the Prime Minister and the Taoiseach rolled up.

The UK is now two prime ministers on. Ireland has had another Taoiseach in between, but Mr Varadkar is now back.

Expect plenty of grip and grin photo opportunities for both leaders.

Downing Street is emphasising that the focus of Rishi Sunak's trip is what they call "community engagements."

"He will speak with a broad range of people from across Northern Ireland including those delivering public services, those supported by them, and their families," No10 told us.

The message appears to be that there has been a weekend of high rhetoric and highfalutin politics - with all the references to history associated with a first nationalist First Minister - but now the focus should be on improving people's day-to-day lives.

A £3.3bn carrot for Northern Ireland was dangled by the government at Westminster to attempt to lure the Democratic Unionist Party back to Stormont and so allow the institutions to be revived.

Northern Ireland Secretary Chris Heaton-Harris, long on negotiating and short on sleep recently, told me that money is now being delivered.

Incidentally, getting the deal over the line sounded punishing. I hear that on one day in the last week, he flew from Belfast to London, back to Belfast and then back to London, all in a day.

Given air miles like that, there is an expectation within government that things should start to get better, that public sector strikes end and the health service, widely seen as in crisis, improves.

Michelle O'Neill says parties at Stormont will be turning their attention to how Northern Ireland is funded

But the new first minister, Sinn Fein's Michelle O'Neill, told me that, despite the dollop of money from London, all the parties in the Stormont Executive agree that Northern Ireland needs a better funding model from Westminster. She means more money.

After a pandemic, soaring inflation, cost of living pressures and two years of political stasis, politicians here are having to manage expectations about how quickly things will change.

Governing, choices, trade-offs, scrutiny - it all begins here. But the vast majority of members of the legislative assembly, or MLAs, are delighted to be back.

"After two years, part of my brain was atrophying," one said.

As for the prime minister, he can point to this moment as an achievement of statecraft, domestic and international.

The deal with the European Union, a year ago, the Windsor Framework.

The deal with the Democratic Unionists now.

It affords Rishi Sunak a chance for a victory lap, albeit one unlikely to garner many votes, on a wider political circuit that, let's be honest, hasn't offered him many such recent opportunities.

Oh, and after Michelle O'Neill's remarks at the weekend about her belief there could be a referendum within 10 years on Northern Ireland becoming part of the Republic, Mr Sunak writes in the Belfast Telegraph that the agreement of the last week "safeguards the union."

He adds "far from being neutral on the Union, I passionately believe in it."

"The shape of Northern Ireland's future is now clear: devolved government, within the United Kingdom, for as long as the majority wish it," he writes.

The question now is how stable devolution will be this time.

Power sharing has a built-in fragility, with the capacity of political parties to bring it crashing down.

Its history is peppered with collapse.

And empowered with new tools to influence Northern Ireland's Brexit arrangements, there are new tools of potential friction too.

Much is new, much is the same, as Stormont returns.

1 year ago

127

1 year ago

127

English (US) ·

English (US) ·