ARTICLE AD BOX

10 minutes ago

By Mark Easton, Home Editor

Getty Images

Getty Images

Despite the risks, many migrants still attempt the dangerous journey across the Channel

If Labour wins the election, the Rwanda policy would become an obscure footnote in the history books.

Labour has no proposal to remove migrants arriving by unauthorised routes to a “safe third country” - so does Keir Starmer’s plan to deal with “illegal” migration stack up?

Let us imagine a small boat of asylum seeking migrants arrives on the Kent coast next month. Aboard are men, women and children from the countries which typically make up arrivals coming across the channel.

Half of the passengers have come from countries so unstable there is no chance they can be returned: Afghanistan, Iran, Eritrea, Syria, Iraq and Sudan. Almost all come from states with which the UK has no agreement to return those not granted asylum.

The Conservatives' answer to this problem has been the Illegal Migration Act (IMA), a law giving the home secretary powers to lock up almost all those aboard the boat and then swiftly remove them to East Africa. The Rwandan government would be handsomely paid to take responsibility for their futures.

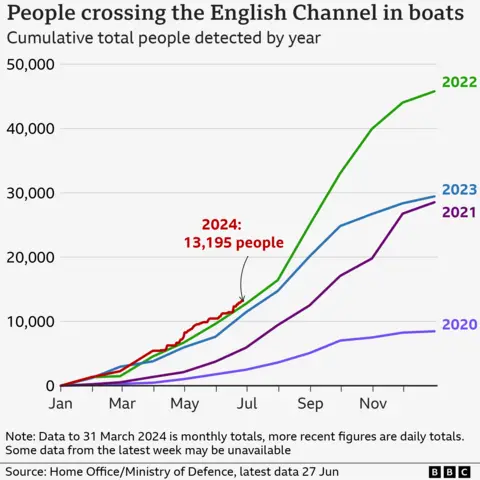

But 40,000 small boat passengers have crossed since the IMA became law last July - and not one person has been dealt with in that way.

Getty Images

Getty Images

A dinghy carrying around 65 migrants crosses the English Channel

Why? Because, at the moment, it simply cannot operate. There isn’t space to detain the tens of thousands who qualify for removal. And even if there was, with flights to Rwanda still grounded, there is nowhere the vast majority can be removed to.

Home Office ministers insist that, if re-elected, the Conservatives would be able to make the policy work, but right now the Rwanda plan is going nowhere.

Instead, we have tens of thousands of people in a legal and social limbo, surviving on around £7 a day, unable to get asylum, to work, or make plans for themselves and their families.

The Refugee Council suggests 36,000 asylum seekers are still living in unsuitable hotel rooms, at a daily cost of £5.3m. And pressure on the system is increasing.

“The next government must restore the right to asylum in the UK and rebuild a system based on British values of compassion, fairness and respect,” says Refugee Council chief executive Enver Solomon.

PA Media

PA Media

Migrants outside a hotel in Pimlico, London

“With tens of thousands shut out of the asylum system, stranded in permanent limbo, a system meltdown is rapidly unfolding.”

The Labour party has described the Rwanda plan as an unworkable gimmick and insists it will scrap the policy.

But what would replace it? What would happen to the occupants of our typical small boat under a Labour government? The party insists Britain should honour its treaty obligations to offer asylum to those genuinely fleeing war or persecution.

Given that most small boat arrivals come from countries with very high rates of asylum acceptance, about two-thirds of the passengers aboard our typical boat would win the right to rebuild their lives in the UK.

Critics argue this approach would encourage more migrants to cross the channel. Labour says it has a plan to defeat the smuggling gangs.

“Where people have no right to be here, they will be removed,” Keir Starmer said this week.

But removed how? And to where?

Reuters

Reuters

Keir Starmer attends a general election campaign event in Macclesfield

Labour says it would negotiate returns agreements with individual states and the European Union, creating a mechanism for those in Britain unlawfully to be removed.

But such deals are far from straightforward. As Rishi Sunak argued in the BBC leaders’ debate this week, you cannot negotiate with the Taliban. In any event, almost all Afghans are granted refugee status and international law would prevent returning the handful who are not.

Would a Labour government want to sign returns agreements with countries which have terrible human rights records? Or are in the grip of civil war? Since Brexit, even negotiating returns agreements with our European neighbours would be challenging.

The EU is about to introduce a system of burden sharing which can require member states to accept additional asylum seekers or make a financial contribution to those bearing the brunt of migration pressures.

One can imagine the political headaches for a British prime minister attempting to navigate the UK’s obligations within a scheme like that.

However, any sustainable solution to the global issue of international migration will require international negotiation.

“The biggest returns deal the UK can plausibly get is a returns deal with the EU,” says Madeleine Sumption of the Oxford Migration Observatory. “It’s possible that a deal with the EU could mean more asylum seekers being returned there than would ever plausibly be sent to Rwanda.”

Sir Keir has stressed his determination to improve the UK’s relationship with the EU. But any deal on migrant returns would come with politically uncomfortable compromise.

The Labour party has said that, if elected, it would set out a “new framework” for dealing with unauthorised migration.

But the details of that have yet to be revealed.

When working out how to treat the individuals aboard a dinghy arriving on the Kent coast, it is, of course, the details which matter. Keir Starmer and his team must know there is no quick and easy way to stop the boats.

4 months ago

18

4 months ago

18

English (US)

English (US)