ARTICLE AD BOX

Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty Images

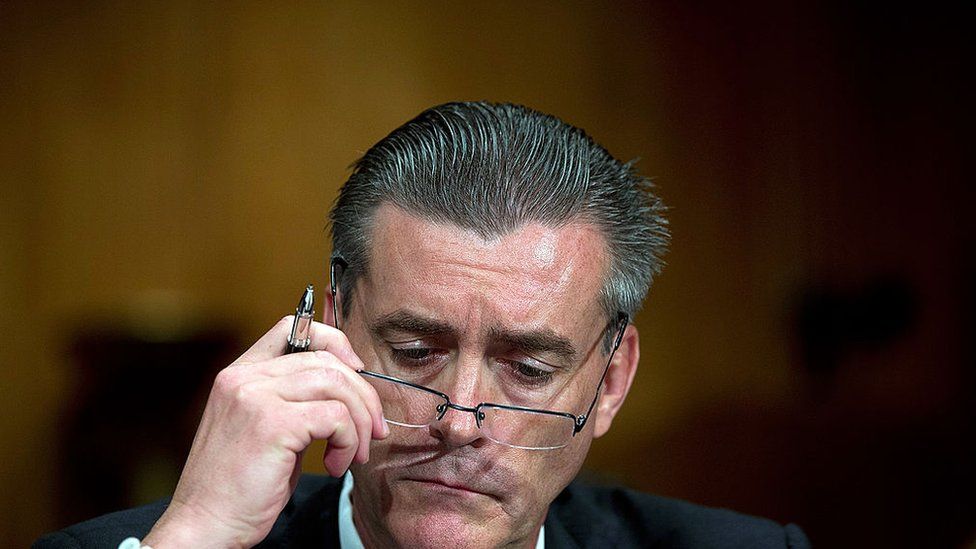

Former Ambassador Olson's conviction has rocked the typically rule-following world of diplomacy

By Holly Honderich

in Washington

In 2012, when Richard Olson reported to Islamabad to begin his posting as US ambassador to Pakistan, the veteran diplomat was faced with an icy welcome from his host country, angered by the United States' military raid a year earlier to kill Osama Bin Laden.

On the surface, Ambassador Olson handled the assignment with skill - the hard-earned product of his 30-plus year career in the foreign service.

When he retired four years later, in 2016, then-Secretary of State John Kerry gushed that Olson, "quite simply one of our most distinguished diplomats", had left a "lasting impact" on US diplomacy.

But behind the scenes, Olson's arrival in Islamabad marked the beginning of a scandal-filled few years, US court documents have shown - extramarital affairs, unreported gifts of diamond jewellery, and accusations of lies and illegal lobbying.

Olson did not respond to a request for comment, but in court filings his lawyer described the former diplomat's career and service to his country as "nothing but honourable".

Still, last year, Olson admitted to lying in ethics paperwork and violating so-called "revolving door" laws by lobbying for Qatar within one year of retiring from federal service. On Friday, was sentenced to three years of probation and ordered to pay $93,400.

Olson's dramatic fall from grace was both a shocking end to a lauded 34-year career and, experts say, a marked aberration in the typically buttoned-up world of US diplomacy. The state department did not return a request for comment on the case.

"If anything the foreign service gets a reputation for blandness. Boring is the quality, usually," said Thomas Alan Schwartz, a history and politics professor at Vanderbilt University. "This case is striking… it seems he took tremendous risk."

Indeed, court documents revealed that Olson's romantic life while in Pakistan may have opened him up to blackmail. The diplomat's arrival in Islamabad marked the start of his relationship with a British journalist working in Pakistan.

Olson and the journalist Muna Habib were in a relationship until 2014, when Ms Habib realised Mr Olson, who was married, was dating other women. His wife was at the time serving as the ambassador to Libya. Olson and Ms Habib later rekindled their relationship and married.

Ms Habib did not return a request for comment from the BBC.

"Ms Habib believed they were dating exclusively, while Amb Olson was not under that same impression," his lawyers wrote in court documents, first reported by the Washington Post.

Image source, Getty Images

Image caption,Olson, pictured here with former US Defence Secretary Robert Gates, held a number of high-profile posts, including US ambassador to the UAE

According to the newspaper, Olson told authorities he had confided in the CIA's Islamabad station chief about his relationship, but court records suggest that he did not report that information to US diplomatic security officials, which he should have done to be in compliance with state department counterintelligence rules.

The two resumed contact early in 2015. Ms Habib had been accepted to Columbia University's journalism programme, but couldn't afford the nearly $100,000 (£80,000) tuition. Olson offered to introduce Ms Habib to Pakistani-American businessman Imaad Zuberi, a high-flying lobbyist with links to US officials, court filings said.

Zuberi, who pleaded guilty in 2019 to falsifying records and tax evasion in connection with his fundraising for US politicians, agreed to pay Ms Habib $25,000 to help fund her Columbia tuition.

In court documents, Olson's lawyers - who did not return a request for comment - insisted the former ambassador had "merely made an introduction", and had committed no wrongdoing given he was not romantically involved with Ms Habib at the time.

Still, experts say Olson's affair was, in itself, reason for concern, especially given the weakened relationship between Pakistan and the US during that period.

"The possibilities there were endless given the situation with the United States and Pakistan, the possibilities for blackmail," Professor Schwartz said. "I could imagine very dire consequences."

The former ambassador also found himself in hot water for an issue concerning another woman - his mother-in-law.

According to court documents, while Olson was serving as the head of the US Consulate in Dubai, the emir sent a delivery to his office - four pieces of diamond jewellery worth $60,000.

Standards of the Foreign Gifts and Decoration Act in effect at the time would have required Olson report any gifts over $285 and either return them or reimburse the federal government for the market value.

Olson did neither, later telling investigators the diamonds were a gift for his mother-in-law, who had moved to Dubai to help take care of his children, and therefore not covered by the gift rules.

In a November 2016 letter, Olson wrote to the state department he could not force his mother-in-law to return the jewellery as the department had requested, "which I think she would regard as robbery".

The state department ultimately closed its investigation without taking action but in court filings, prosecutors called the emir's jewellery "an exorbitant and obviously inappropriate gift", claiming Olson lied to dodge accountability.

This allegation seems less serious than the affair, Professor Schwartz said, though it still suggests an "ethical blindness".

Olson was not charged for either of these two incidents - the affair and the diamonds. But both were cited by prosecutors as evidence of a pattern of bad behaviour and "unethical gifts" - evidence they used to seek a harsher sentence.

Image source, Getty Images

Image caption,Olson pleaded guilty to two misdemeanour charges

Olson ultimately escaped jail, but had faced up to six months in prison following his guilty plea to two misdemeanour charges.

In the first, Olson admitted to lying about receiving a first-class roundtrip airfare from lobbyist Imaad Zuberi while still employed by the federal government. The trip, from New Mexico to London, was for Olson to attend a job interview with an unidentified Bahraini businessperson who offered Olson a $300,000 annual contract at their company. The roughly $20,000 bill for flights and a luxury hotel was covered by Zuberi.

Olson also admitted to providing "aid and advice" to the Qatari government within one year of his November 2016 retirement - violating federal laws mandating that government employees take a one-year cooling off period before beginning such lobbying work.

"It's not unusual that foreign service officers retire and then might be involved in similar work… but this type of thing is far beyond that," Mr Schwartz said.

1 year ago

36

1 year ago

36

English (US)

English (US)