ARTICLE AD BOX

Aimee Welch

Aimee Welch

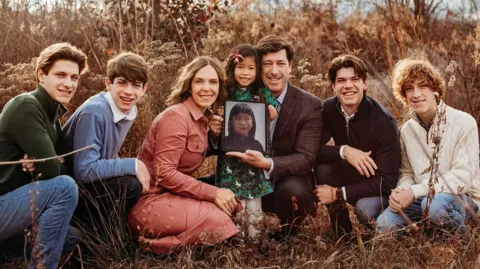

The Welch family with a photograph of Penelope, whom they have committed to adopt

Eight-year-old Grace Welch has been waiting since 2019 for her older sister to occupy the bed next to hers.

Her parents had told her that, Penelope, a 10-year-old born in China, would be joining the family, who live in Kentucky in the US.

Grace, also adopted from China, was born without her left forearm. Her mother, Aimee Welch, said Penelope too has a “serious but manageable” special need, although she did not wish to disclose it.

The Welch family, who have four biological sons, sought to adopt children with disabilities after the birth of a nephew without arms.

“He taught us all what a person with limb differences can achieve with the right love and support. His birth started us on the path towards adopting Grace,” Ms Welch said. “We believe in the dignity and worth of each person, just as they are, in all their diversity.”

But the pandemic delayed their plans.

Then in September, China announced that it was putting a stop to international adoptions, including cases where families were already matched with adoptee children.

The painful wait will particularly determine the fates of China’s most vulnerable children - those with special needs.

Up-to-date statistics are not readily available, but Beijing’s civil affairs ministry said that 95% of international adoptions between 2014 and 2018 involved children with disabilities.

Aimee Welch

Aimee Welch

Grace, 6, has been waiting since 2019 for her older sister to occupy the bed next to hers

These children “will have no future” without international adoption as they are unlikely to be adopted domestically, says Huang Yanzhong, a senior fellow at the US-based Council on Foreign Relations.

Ms Welch said Grace was especially saddened by the news that Penelope may never come home: “She told me, ‘We were meant to be a family of eight so that everyone could have a buddy.’”

Ms Welch called on China to “keep the promises made to the children already matched with adoptive parents”.

Beijing has not commented since the September announcement, when it thanked families for their “love in adopting children from China". It said the ban was in line with international agreements and showed China’s “overall development and progress”.

Disabled life in China

China began allowing international adoptions in 1992 as the country was opening up, and they peaked in the mid 2000s. More than 160,000 children have been adopted by families across the world in the last three decades.

A contentious one-child policy had forced families to give up children, especially girls and kids with special needs. Social stigma around disability had also led to more children with special needs ending up in orphanages.

Dani Nelson, who was adopted to the US in 2017, said she was given basic care at an orphanage in the southwestern city of Guiyang, but it was “not enough for me to live a normal life”.

The 21-year-old was born with spina bifida - a spinal defect - and hydrocephalus, which is a neurological disorder that causes water to gather around her brain.

In her first three years in the US, she had seven surgeries which she said helped her “lead a normal life”.

“I joined a swim team. I got a job… Adoption saved my life,” said Ms Nelson, who now works as a cashier at a coffee shop.

Like in many Asian societies, disabled people in China face discrimination and are sometimes even seen as a source of “bad luck”.

China has made some strides in improving accessibility to the disabled, but public infrastructure, especially in rural areas, are still weaker than countries in the West. It has only recently started developing education institutions and curricula for students with special needs.

Only the most seriously disabled receive financial support from the government.

The BBC had previously interviewed Chinese adults with special needs whose parents have had to stop working to care for them.

Aware of these challenges, waiting families are concerned about what will happen to the children they were meant to adopt, some of whom need urgent medical treatment.

Meghan and David Briggs were matched with a boy in Zhengzhou, Henan, in 2020. The 10-year-old has a “moderate special need that requires medical intervention”, Mrs Briggs said.

The couple live with their biological son, also 10, in Pennsylvania. Mr Briggs said the family made a “wilful choice” to adopt a child who is more vulnerable and less likely to get the specialised care and therapy in an institution in China than with a family in the US.

“Such care is a financial and emotional responsibility. We were prepared to offer this care because we view this child as our family,” said Mr Briggs, who himself was adopted from South Korea.

“He was promised a family by his own government,” Ms Briggs said. “The children are the ones who will suffer with this decision,” she said.

Meghan Briggs

Meghan Briggs

David and Meghan Briggs, seen here with their biological son, were matched with a boy in Zhengzhou in 2020

A sense of relief for some

Not everyone agrees.

Some, including adult adoptees, are relieved about that Beijing has ended foreign adoption.

“My experience as a transracial adoptee being raised in a predominantly white, Christian city is that you often get looked down upon. I was constantly reminded that I don’t belong,” said Lucy Sheen, who was adopted by a white family in the UK.

Ms Sheen, now in her 60s, added that her adoptive family had little knowledge of her Chinese culture and heritage. She was once told off for asking to learn Mandarin.

“Some adopters have a ‘white-saviour’ mentality or have the ideology that they are bringing us where they come from because ‘West is best’, I think that needs to change,” she added.

Nanchang Project, a non-profit group that helps connect adoptees to their roots in China, said it felt “a sense of relief that no more children will be separated from their birthplace, culture, and identity”.

“We hope this moment can shift focus toward the need for post-adoptive services to support Chinese adoptees and their families for the rest of their lives,” the group said in a statement last month.

Under the new policy, China will only send children overseas for adoption if the adoptive parents are blood relatives. The BBC understands that US authorities are in talks with Beijing on whether a further exception can be made for waiting families.

John and Anne Contant who were matched with five-year-old Corrine in 2019, said they “honour China’s decision to change course on their adoption policy”.

“If there have been more families wanting to adopt domestically, that’s wonderful… Our ask is for these 300 children who have been matched [to families in the US] to be allowed to come home,” he said.

The couple live in Chicago with six children. Three of them were adopted from China and live with albinism, as does Corinne.

The Contants spoke to Corinne via WeChat when their plans to travel to China were shelved because of the pandemic.

“Corinne met our children, saw her home and the room that had been prepared for her, and experienced the excitement our children felt in preparation for her arrival,” Mr Contant said.

“In one of our conversations, she pointedly asked, ‘When are you coming to get me?’”

1 month ago

12

1 month ago

12

English (US)

English (US)