ARTICLE AD BOX

Image source, Family handout

Image source, Family handout

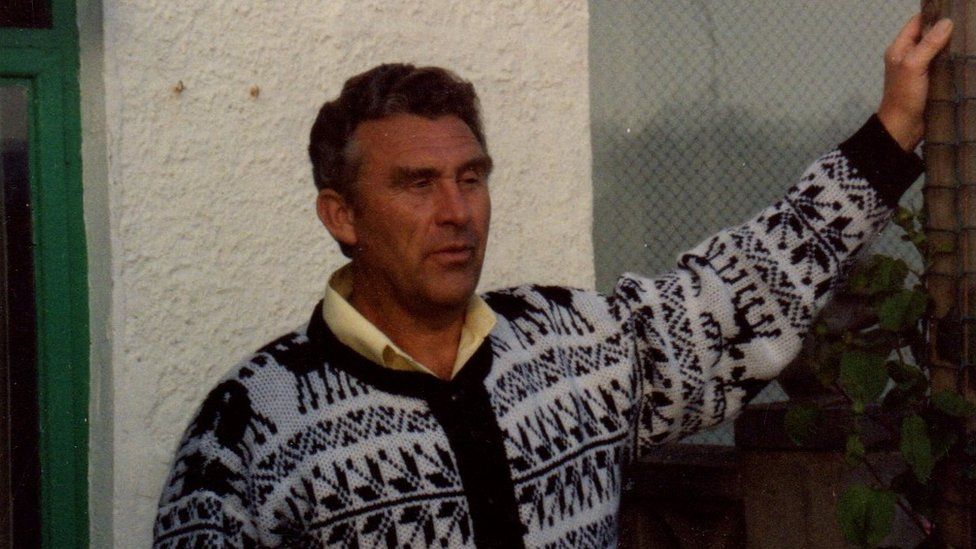

Robert Murray, pictured in 1992, died after paramedics were stood down due to a do not resuscitate order

By Michael Buchanan

Social affairs correspondent, BBC News

Experts are calling for "do not resuscitate" orders to be scrapped, saying they are being misused and putting people's lives at risk. One woman told BBC News that her elderly father may still be alive if the DNR in his medical file had been properly checked.

When Robert Murray began choking on a piece of fruit at breakfast, staff at his care home called 999. He'd stopped breathing and the ambulance service operator immediately sent paramedics to attend.

But seconds later, the care home told the dispatcher that the 80-year-old had a do not resuscitate form (DNR) in his medical records. The paramedics were stood down. Mr Murray died minutes later.

However, it was all a terrible mistake. It hadn't been made clear to the ambulance service that Mr Murray was choking - the DNR was only meant to apply should he have a cardiac arrest.

"As soon as you say DNR, it seems to change what they want to do," says Robert's daughter, Wendy, who heard the 999 call during an inquest into her father's death.

"If his heart was failing - he was having a heart attack - I could totally understand that. But when he died of a choking incident, which is not a natural way of dying, it didn't get picked up."

Image source, Family handout

Image caption,Mr Murray had a DNR order in place since 2016. He died in 2021

Wendy says her father was a kind and patient dad. He'd been diagnosed with early on-set Parkinson's when he was 55.

Despite this - and even after the death of his wife from kidney cancer in 2011 - Mr Murray continued to live at home until 2019, when he finally decided he needed to move to a home for round-the-clock care.

"He had a DNR in place since 2016," says Wendy. "He completely agreed with it. It was mainly for his heart, as he had a murmur, but he never wanted to come back [if something happened] from Parkinson's.

"He was on quite strong medication, he had shakes, it took him a lot to time to get himself moving."

Mr Murray's death, at a nursing home in Eastbourne in June 2021, is an example of what experts call "mission creep" in the use of DNR - also known as DNACPR (Do Not Attempt Cardiac Pulmonary Resuscitation) - decisions.

Researchers from Essex University say some care home residents are "being inappropriately denied transfer to hospital or access to certain medicines" due to the recommendations.

Wendy Murray believes her father would "probably still be alive" if the DNR had been properly checked

DNR and DNACPR decisions are intended to inform clinicians how someone should be treated if their heart or breathing stops.

The decisions are not legally binding. But they can be appropriate if a person is unlikely to withstand the procedure and can be mandated by a doctor - but crucially only after they've consulted with the patient, or their family.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, concerns were raised that such decisions were being taken on a blanket basis. Care homes for both elderly and disabled people were accused of making recommendations without considering the merits of individual patients.

A 2021 investigation by the care watchdog, the Care Quality Commission, found there may have been more than 500 breaches of individual human rights due to the misuse of DNR decisions.

The Essex University research suggests potential confusion around orders. In a small study of 262 care professionals, most of whom had responsibility for applying the 2005 Mental Capacity Act, researchers found:

- 17% said they'd seen instances of DNACPR decisions informing care and treatment decisions beyond their intended use

- 28% said they'd seen DNACPR forms added to medical notes due to blanket decisions, such as the age of a resident

- 55% reported witnessing decisions being made without consultation with the resident or their family

In a subsequent focus group carried out by the university, one participant said: "Some staff see DNR as 'do not care', or 'do not seek any medical treatment'."

The forms have come to be used "to inform other medical decisions, around eligibility for hospital care, people being refused IV medication," says Professor Wayne Martin, who led the research.

"That's what we call mission creep - its not what these forms were designed for. It's really a violation of both law and people's rights to care."

Researchers are calling for better training for both care professionals and those advocating for them. But Professor Martin says the starting point should be to "get rid of DNACPR forms", adding: "They look like they're an order, when they're not legally binding."

Researchers say new standardised documentation - based on consultation, a person's individual circumstances, and a clear understanding of the law - are needed.

Image source, Family handout

Image caption,Mr Murray and his wife on their wedding day in 1964

For Wendy Murray, it will all come too late. The pandemic meant that she never got to hug or touch her father for over a year before his death.

"He would probably still be alive if they'd actually brushed up on what they needed to do, double checking what is in the DNR, not the fact that, 'Oh, he's got a DNR in place, we won't bother.' It's not a nice way to lose your parent."

The home in which Mr Murray was staying, Avalon Nursing Home, in Eastbourne, said it had updated advice relating to DNACPR forms in all care plans, and that staff had attended refresher training on basic life support.

2 years ago

48

2 years ago

48

English (US) ·

English (US) ·