ARTICLE AD BOX

Nikhil Inamdar, BBC News, Mumbai

Getty Images

Getty Images

Data from India's weather agency shows that last month was India's hottest February in 125 years

A shorter winter has literally left Nitin Goel out in the cold.

For 50 years, his family's clothing business in India's northwestern textile city of Ludhiana has made jackets, sweaters and sweatshirts. But with the early onset of summer this year, the company is staring at a washout season and having to shift gears.

"We've had to start making t-shirts instead of sweaters as the winter is getting shorter with each passing year. Our sales have halved in the last five years and are down a further 10% during this season," Goel told the BBC. "The only recent exception to this was Covid, when temperatures dropped significantly."

Across India as cool weather beats a hasty retreat, anxieties are building up at farms and factories, with cropping patterns and business plans getting upended.

Nitin Goel

Nitin Goel

Winter clothes manufacturers say retail clients have been hesitant to pick up even confirmed orders due to soaring temperatures

Data from the Indian Meteorological Department shows that last month was India's hottest February in 125 years. The weekly average minimum temperature was also above normal by 1-3C in many parts of the country.

Above-normal maximum temperatures and heatwaves are likely to persist over most parts of the country between March and May, the weather agency has warned.

For small business owners like Goel, such erratic weather has meant much more than just slowing sales. His whole business model, practised and perfected over decades, has had to change.

Goel's company supplies clothes to multi-brand outlets across India. And they are no longer paying him on delivery, he says, instead adopting a "sale or return" model where consignments not sold are returned to the company, entirely transferring the risk to the manufacturer.

He has also had to offer bigger discounts and incentives to his clients this year.

"Big retailers haven't picked up goods despite confirmed orders," says Goel, adding that some small businesses in his town have had to shut shop as a result.

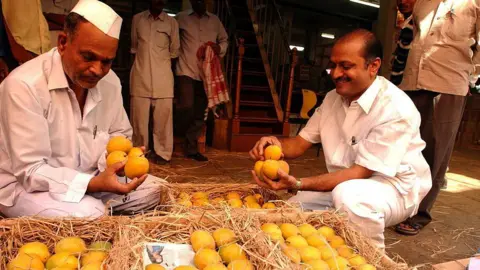

Getty Images

Getty Images

Heat has reduced yields at India's much-loved Alphonso mango orchards on the country's western coast

Nearly 1,200 miles away in Devgad town on India's western coast, the heat has wreaked havoc on India's much-loved Alphonso mango orchards.

"Production this year would be only around 30% of the normal yield," said Vidyadhar Joshi, a farmer who owns 1,500 trees.

The sweet, fleshy and richly aromatic Alphonso is a prized export from the region, but yields across the districts of Raigad, Sindhudurg and Ratnagiri, where the variety is predominantly grown, are lower, according to Joshi.

"We might make losses this year," Joshi adds, because he has had to spend more than usual on irrigation and fertilisers in a bid to salvage the crop.

According to him, many other farmers in the area were even sending labourers, who come from Nepal to work in the orchards, back home because there wasn't enough to do.

Scorching heat is also threatening winter staples such as wheat, chickpea and rapeseed.

While the country's agriculture minister has dismissed concerns about poor yields and predicted that India will have a bumper wheat harvest this year, independent experts are less hopeful.

Heatwaves in 2022 lowered yields by 15-25% and "similar trends could follow this year", says Abhishek Jain of the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (Ceew) think tank.

India - the world's second largest wheat producer - will have to rely on expensive imports in the event of such disruptions. And its protracted ban on exports, announced in 2022, may continue for even longer.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Three out of every four Indian districts are "extreme event hotspots" according to one estimate

Economists are also worried about the impact of rising temperatures on availability of water for agriculture.

Reservoir levels in northern India have already dropped to 28% of capacity, down from 37% last year, according to Ceew. This could affect fruit and vegetable yields and the dairy sector, which has already experienced a decline in milk production of up to 15% in some parts of the country.

"These things have the potential to push inflation up and reverse the 4% target that the central bank has been talking about," says Madan Sabnavis, Chief Economist with Bank of Baroda.

Food prices in India have recently begun to soften after remaining high for several months, leading to rate cuts after a prolonged pause.

GDP in Asia's third largest economy has also been supported by accelerating rural consumption recently after hitting a seven-quarter low last year. Any setback to this farm-led recovery could affect overall growth, at a time when urban households have been cutting back and private investment hasn't picked up.

Think tanks like Ceew say a range of urgent measures to mitigate the impact of recurrent heatwaves needs to be thought through, including better weather forecasting infrastructure, agriculture insurance and evolving cropping calendars with climate models to reduce risks and improve yields.

As a primarily agrarian country, India is particularly vulnerable to climate change.

Ceew estimates three out of every four Indian districts are "extreme event hotspots" and 40% exhibit what is called "a swapping trend" - which means traditionally flood-prone areas are witnessing more frequent and intense droughts and vice-versa.

The country is expected to lose about 5.8% of daily working hours due to heat stress by 2030, according to one estimate. Climate Transparency, the advocacy group, had pegged India's potential income loss across services, manufacturing, agriculture and construction sectors from labour capacity reduction due to extreme heat at $159bn in 2021- or 5.4% of its GDP.

Without urgent action, India risks a future where heatwaves threaten both lives and economic stability.

Follow BBC News India on Instagram, YouTube, X and Facebook.

5 hours ago

2

5 hours ago

2

English (US) ·

English (US) ·