ARTICLE AD BOX

By Fergal Keane

BBC News

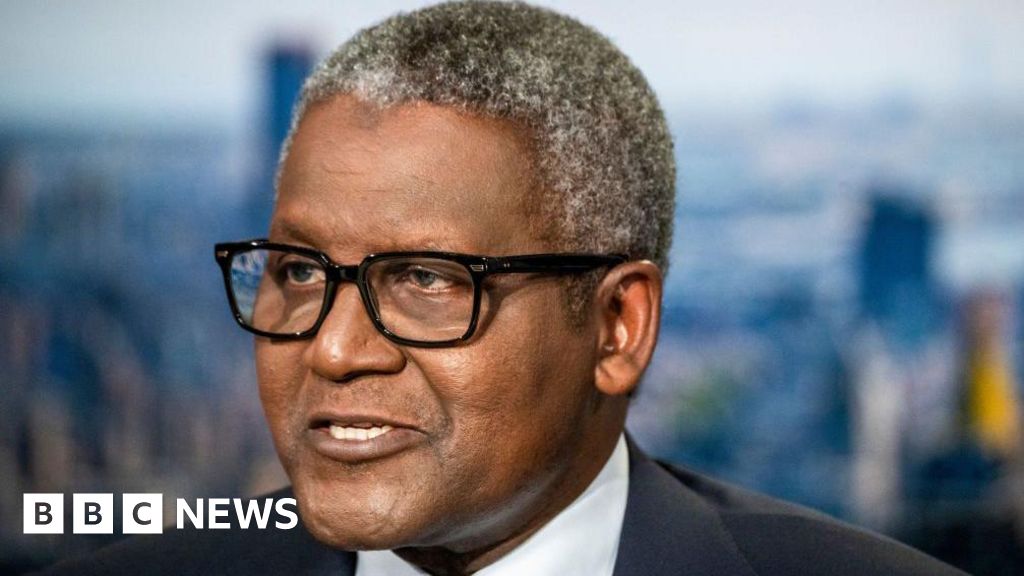

Fergal has used a combination of therapy and medication to treat his PTSD

The horrific scenes of war emerging from Ukraine have raised fresh concerns about the trauma experienced by those who witness extreme violence. PTSD - Post Traumatic Stress Disorder - affects millions worldwide. The BBC's Fergal Keane, who was diagnosed in 2008, explores its effects and the potential for healing.

All day and much of the night I went back and forth in my mind. Do I stay, or go? It was around mid-February and I was certain that war was coming to Ukraine. From my hotel room in Kyiv I looked out on a skyline that might soon be lit by the fire of explosions.

The part of me that wanted to tell one of the biggest stories of my lifetime longed to stay. But it is also the part that is drawn to danger and has brought anguish into my personal life in the form of PTSD.

What I knew for certain, was that staying on under what I suspected then might be a constant bombardment, along with street fighting, would place my mental health in grave danger.

Did I really want to end up in hospital again, my nerves jumping at any loud noise, unable to sleep, exhausted by the depression that invariably comes with my PTSD, and the sense of guilt at the stress felt by my loved ones watching me report from an active frontline? I had also publicly committed to give up war reporting several years before.

I booked a flight and went home the following morning.

Yet soon afterwards, I was in Lviv in the far west of Ukraine reporting on the massive flow of refugees heading to western Europe. A few friends messaged asking why I was there after promising publicly to avoid war reporting. My rationale was that I was not under fire in Lviv. It was too far west for the Russians to come.

It was a way of covering the story without being in danger. Which is true. But being in Lviv was also part of my internal struggle. I could not entirely leave the war zones behind.

In 30 years, Fergal has reported on numerous wars and civil conflicts

It was during the making of my BBC documentary on PTSD that I began to seriously consider the addictive nature of war reporting in my own case. Yes, I was a journalist with a deep curiosity about the world and particularly how human beings behave in extreme situations.

History and how it plays out in modern conflicts is also a passion of mine, and I have always felt that the work of witness is central to upholding human rights.

In 30 years, I've reported on numerous wars and civil conflicts - from Belfast during the Troubles to genocide in Rwanda, to Iraq, Afghanistan and Ukraine.

But there was a less healthy aspect to my choice of work. War repeated the nervous stress, and the powerful compulsion to prove I could survive, that I had experienced as a child growing up in a home fractured by the effects of my dad's alcoholism. In war zones I could prove I was no longer a scared child. I had a voice.

Since being given my official diagnosis back in 2008, I have used a combination of therapy - the "talking cure" - and anti-depressant medication. My therapy was CBT - Cognitive Behavioural Therapy - which examines negative thoughts associated with trauma and tries to replace them with positive ones.

The mix of talking and medication have helped to ease the symptoms and show me a healthier way to live. It has also been more than 20 years since I had a drink - for years before I tried to medicate the pain inside with alcohol.

- Nightmares, flashbacks, ruminating on the traumatic experience

- Avoidance of images, thoughts, places which could trigger anxiety related to the trauma

- Hyper vigilance - constantly on the alert for potential threats to your physical wellbeing

- Hyper arousal - exaggerated responses to noises, smells, movements

- Emotional detachment which can cause a feeling of being numb

- Short temper

- Depression

If you have been affected by any of the issues in this story you can visit BBC Action Line

Fergal Keane - Living with PTSD is broadcast on BBC2 on Monday 9 May at 21:00 BST, as part of Mental Health Awareness Week.

It is estimated that three in 100 adults in the UK have experienced PTSD. Victims of rape, assault, domestic violence, and survivors of accidents are among those who can develop symptoms.

I cannot stress enough that each individual mind, and traumatic experience, calls for an individual approach. The best mental health professionals realise they are dealing with individuals and not cases to be slotted under pre-determined labels.

Researching for the BBC film Living With PTSD, I had a chance to examine the different treatments now being used to treat the disorder: from therapy through the use of medications, including experiments with the drug MDMA. It stimulates the release of neurotransmitters in the brain which can create a mood of empathy, making therapy more beneficial.

MDMA treatment is being clinically trialled in Britain but is not yet approved for general use. Another method being explored is the use of video games, like the puzzle Tetris, which can ease stress in the brain. Trials in the US and Britain have showed beneficial effects.

I have been lucky to have the support of my employers and the love of family and friends. These are essential weapons in the battle against the loneliness and lack of self-worth that are so much part of my experience of PTSD.

Fergal visited the WAVE Trauma Centre in Belfast as part of his film

I have also been helped enormously by listening to the experiences of others who have struggled with PTSD. In the course of making the film, I visited the WAVE Trauma Centre in Belfast, which provides therapy and emotional support to survivors of Troubles-era violence. One study - carried out over a decade ago - found Northern Ireland had the highest rates of PTSD in the world. More than 50% of those surveyed had suffered mental health problems related to the Troubles.

At WAVE, I sat with a group that included a woman blown up in an IRA bomb attack which killed her fellow passenger; a man who was shot by terrorists at work, and the remarkable Peter Heathwood, who was paralysed from the waist down in a gun attack by Loyalists in 1979. His father arrived on the scene as paramedics were taking Peter to the ambulance. Because they had no blankets, the crew had placed Peter in a body bag to keep him warm. When his father saw this he assumed Peter was dead and had a fatal heart attack on the spot.

His wife, Anne, who had answered the door when the gunmen knocked, never recovered from the trauma of that day. "There were no sort of therapies back then," Peter recalls. "I'll never forget it, the eyes were like stone, as if she was a statue. You could talk to her but there was no answer." Anne began to drink heavily and died at the age of 51.

Peter regrets that his wife didn't have access to the talking therapy he has been able to experience at WAVE. "Unfortunately, I never knew about it at the time, but I really couldn't emphasise the importance of us talking, and getting people who have the same problems, who are out there today, to know what we can offer them and get them in here to be talked to."

The group asked if I would say a few words. I told them what I was feeling at that moment. That it was humbling to sit with them, to be among people who had suffered so much, and yet found the courage to talk, and to help each other. I told them they inspired me, and if there is to be healing for people like me it starts by reaching out to people who understand. I said that being with them was like coming home. I felt hope.

Fergal Keane - Living with PTSD is broadcast on BBC2 on Monday 9 May at 21:00 BST, as part of Mental Health Awareness Week.

2 years ago

23

2 years ago

23

English (US)

English (US)