ARTICLE AD BOX

By Lucy Williamson

BBC Paris correspondent

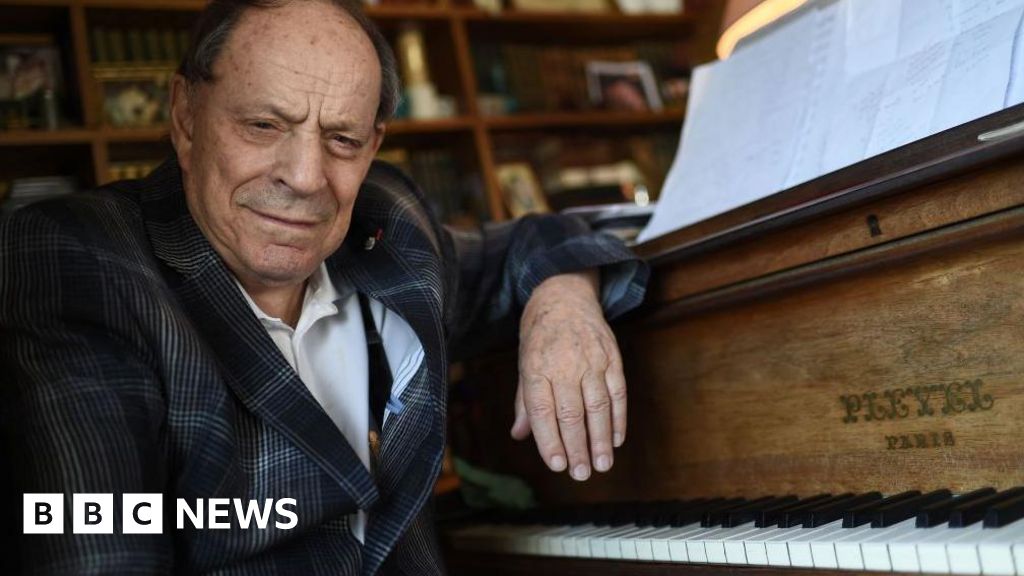

Image source, Laurène Casseville/BBC

Image source, Laurène Casseville/BBC

Having beaten the far right to retain the presidency in April, France's leader Emmanuel Macron is facing an unexpected challenge from a former Marxist on the far left.

A new five-party alliance led by Jean-Luc Mélenchon is expected to make sweeping gains in legislative elections here on Sunday, possibly even blocking the government's majority in France's 577-seat National Assembly.

And, with the directness that he's known for, Mr Mélenchon, who leads the far-left La France Insoumise (France Unbowed) party, has chosen a simple slogan for his campaign posters: "Mélenchon: prime minister."

"The threat is clearly there. If we look at the polls, we are very close," government candidate Paul Midy told me, as he chatted to voters at a market in Essonne, south of Paris.

Mr Midy is running as a candidate for President Macron's centrist alliance Ensemble! (Together).

Image source, Laurène Casseville/BBC

Image caption,Paul Midy says the priority is for President Macron to secure a majority

While purchasing power remains the core concern at a national level, voters here in Essonne were very concerned about green issues, he told me, especially the opening of a new science research institute next to fertile farmlands.

"We [host] Paris Saclay, one of the major innovation clusters in the world, with thousands of researchers; it's our French Silicon Valley," Mr Midy explained. "We need to develop it, but we also need to protect all the farmlands around it."

Mr Mélenchon's alliance, known as NUPES (the New Ecological and Social Popular Union), includes France's main green party, along with the Socialists, the Communists, and France Insoumise.

The NUPES candidate running against Paul Midy in Essonne is Cédric Villani. He turns up at the market on his bicycle, his basket stuffed with campaign leaflets.

"There are some huge differences [within NUPES] that are well known, especially on international policy," Mr Villani said. But we agree on the ecology and solidarity programme, which is very strong. When there's a vote about Europe, we'll be free to vote however we feel is best."

Image source, Laurène Casseville/BBC

Image caption,Cédric Villani (R) switched from the president's party to the greens two years ago

I ask Mr Villani, a committed fan of the EU, whether he would want the Eurosceptic, Nato-sceptic Mr Mélenchon as prime minister.

"Let's do things in the right order," he smiles. "The little bit of political experience I have now has taught me there are some questions that need to be postponed."

The campaign in Essonne is more awkward than most, because Mr Villani - who came into politics with Mr Macron's party in 2017 - swapped political allegiance two years ago to the greens.

"I'm spending this whole campaign explaining that I'm the candidate of Macron, and [my opponent] is the candidate of Jean-Luc Mélenchon," Paul Midy told me.

"In France, if you want to be able to pass reform, you need to have a clear majority in parliament. So this election is to get a clear majority for Mr Macron."

A few weeks ago, analysts say, it was unthinkable that Mr Mélenchon's new alliance would seriously threaten the government's majority.

Mr Macron and his allies currently have 345 seats in parliament - far more than the 289 they need for a majority.

But the range of results expected by pollsters here has shifted, with the lowest projections for Ensemble! dipping below that magic number of 289.

NUPES, some say, could tip 200. France Insoumise itself currently has fewer than 20 MPs.

That's quite a turnaround for the political left in France, all but forgotten in the battle between Mr Macron and the right.

"It's because all the parties on the left have united for the legislative elections," political scientist Olivier Costa explained.

By contrast, he says, the far-right parties couldn't agree on joining forces, which has left the National Rally party of Marine Le Pen isolated.

And, he says, some voters who backed President Macron in the presidential run-off simply to block Ms Le Pen, now want to limit his power.

"There's a strong feeling that, OK, we elected Macron because it was him or Marine Le Pen, but we're going to try and put him in a challenging situation," he said.

"I think Mélenchon has no chance of winning a majority, but what he can do is make a pretty good score and then constrain Macron to be in a sort of permanent negotiation."

It's enough of a threat that President Macron himself has suddenly appeared on the campaign trail, in support of his MPs, after weeks of noted absence.

Image source, EPA

Image caption,Without a majority President Macron will struggle to push through his policies

After his first term was derailed by protests, Covid and the war in Ukraine, Mr Macron is keen to get a good run at the second, and "permanent negotiation" with parliament isn't part of the plan.

But some voters say more negotiation might be good for a president who's widely seen as arrogant.

"It will slow them down a bit, but it won't stop them from succeeding," public-sector worker Charlotte said as she left the market in Essonne. "For me, it's not a bad thing to have different parties."

Perhaps the possibility of real debate will encourage voters to turn up for the election on Sunday - and for the run-off vote on 19 June. But for now, predictions are that turnout will be lower than ever.

"French people know that the power lies in the Elysée," Prof Olivier Costa said. "And Emmanuel Macron has a very centralised approach. So people have the feeling that the National Assembly doesn't weigh very much in the decision-making process."

It's all part of what he calls the "French madness" in politics. "It's just a competition between a limited number of leaders with a giant ego."

So is France's parliamentary election just another round in the presidential race?

Jean-Luc Mélenchon likes to say so. Remember his campaign literature, emblazoned with the words "prime minister"?

Back in the market in Essonne, Paul Midy accepts that there's truth in it. "It's a long road to power in France," he sighs.

2 years ago

18

2 years ago

18

English (US)

English (US)