ARTICLE AD BOX

Image source, JOYCE NALTCHAYAN

Image source, JOYCE NALTCHAYAN

Northern Ireland has been visited by three sitting US presidents since the Good Friday Agreement

By Chris Page

BBC News Ireland Correspondent

For a place roughly the size of Connecticut, Northern Ireland has received plenty of presidential attention.

Bill Clinton visited three times during his presidency, George W Bush twice, and Barack Obama once.

It is sometimes said that the United States is the "third guarantor" of the Good Friday Agreement - after Britain and Ireland, which are the two nations charged in international law with upholding the deal.

Ancestral links are the bedrock of the bonds between the US and the island of Ireland.

It had long been expected that Joe Biden - a president who speaks of his Irish roots more than most - would visit Northern Ireland to mark the 25th anniversary of the peace deal which largely ended the conflict known as the Troubles.

However, the circumstances are less than ideal.

Image source, Charles McQuillan

Image caption,Northern Ireland has been without a power-sharing government since February 2022

The power-sharing political institutions set up by the agreement have not been fully operating for more than a year.

The Democratic Unionist Party is vetoing the formation of a devolved government in protest against Brexit trading arrangements for Northern Ireland.

The DUP has said it will not allow a coalition to be formed until it is satisfied there are no economic barriers between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK.

The White House has welcomed the deal between the UK and the EU, known as the Windsor Framework, which is designed to deal with unionists' concerns.

The British government is hoping Mr Biden's visit will promote the framework as the internationally recognised way forward.

Image source, PACEMAKER

Image caption,Expect to hear politicians blame the DUP for a "missed opportunity" on Mr Biden's visit

Other parties have suggested the presidential itinerary would have been more comprehensive if the Northern Ireland Assembly was up and running.

President Biden had been invited to address the assembly, at Stormont on the outskirts of Belfast.

But the invitation from the Assembly Speaker, Alex Maskey, was not accepted.

So you can expect the likes of Sinn Féin - the Irish nationalist party which is now the largest in the assembly - to blame the DUP for a "missed opportunity".

However, the DUP will point to the basis of the power-sharing settlement backed by the US - that both unionists and nationalists must have confidence in the governance arrangements for Northern Ireland in order for them to work.

Some DUP politicians have been strident in criticising President Biden for his backing of the Northern Ireland protocol - the previous deal between the UK and the EU after Brexit, which created a trade border in the Irish Sea.

Image source, Charles McQuillan

Image caption,Tony Blair (left) said Bill Clinton immediately understood the political situation in Northern Ireland

Over the years nationalists have been more enthusiastic about US input than unionists, who have been suspicious of influence being exerted in Washington by lobby groups and politicians who identify as Irish-American.

If previous US diplomatic tactics are anything to go by it is unlikely that President Biden's public remarks in Northern Ireland will be accusatory towards any one party or group.

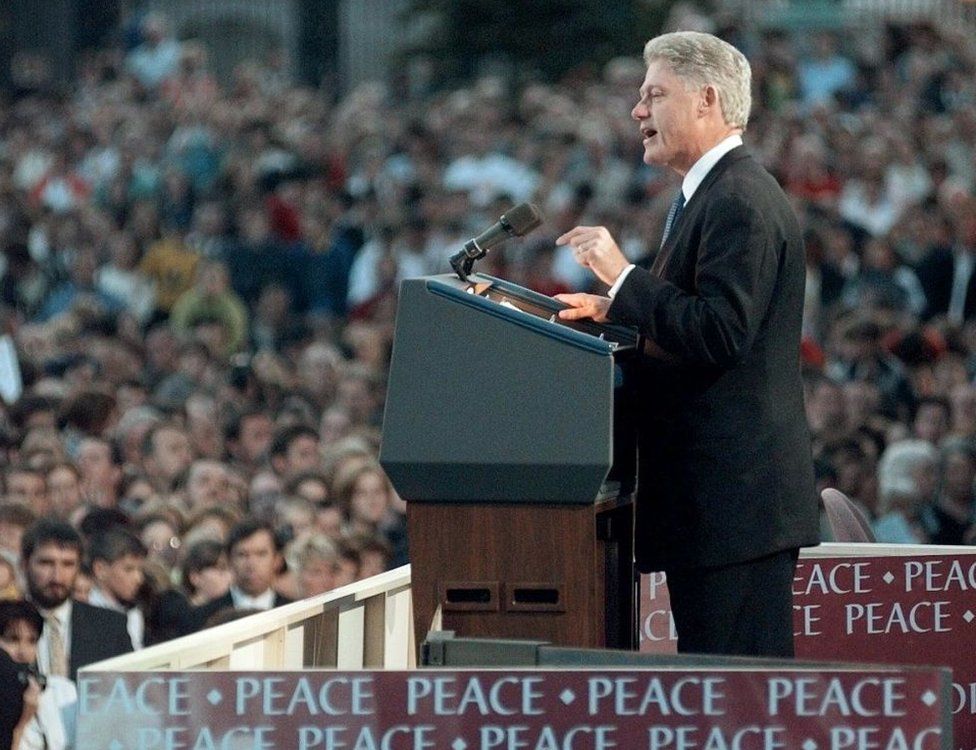

He was on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in the 1990s when Bill Clinton - another Democrat - demonstrated his commitment to the peace process by becoming the first president to visit Northern Ireland while in office.

The British prime minister at the time, Tony Blair, spoke to me about Mr Clinton's approach in an interview for the BBC iPlayer film, 'Troubles and Peace'.

He said that when he called Mr Clinton, the then president "would immediately understand the politics of the situation - who to call, what to do, what to say, how to frame it".

"It meant you had the power of the United States behind you - not just in itself, but also operating with immense sophistication and subtlety," Mr Blair said.

Bríd Rodgers said the Good Friday Agreement would not have been achieved without former US President Bill Clinton

Bríd Rodgers was a negotiator for the Irish nationalist Social Democratic and Labour Party - whose leader, John Hume, prioritised building relations with the White House.

She said: "If it hadn't been for President Clinton in the last 24 hours before the Good Friday Agreement, I don't think we would have got it.

"He was in touch, he was phoning. He recognised unionists' difficulties, he recognised republicans' difficulties - he was able to assure them that he understood their challenges, but he was behind them."

A unionist negotiator, Lord Empey, was more circumspect about Mr Clinton's role during the final hours.

The Ulster Unionist Party peer said: "I don't think it made any difference to the minutiae or the outworkings of the agreement."

He thinks Mr Clinton's most significant contribution came over a longer period of time.

"President Clinton changed the atmosphere, so that America was no longer seen as totally supportive of Irish nationalism.

"No matter what his personal opinions may have been, he made an effort to treat us equally to others - we were no longer shut out."

Lord Empy said Mr Clinton "changed the atmosphere" by treating negotiators equally

Mr Clinton was the first president to appoint a US special envoy to Northern Ireland.

The political influence of some has been obvious - notably George Mitchell, the former Senate Majority leader who was appointed chair of the Good Friday Agreement talks by the British and Irish governments.

In more recent years, envoys have been seen as having significant roles in generating investment in Northern Ireland by US business.

The present holder of the post, Joe Kennedy III, has the official title of Special Envoy for Economic Affairs.

He will be staying on in Northern Ireland for an extended visit after Mr Biden leaves, to tour various locations in the Republic of Ireland.

It is on this leg of the trip that the president will meet his cousins the Finnegans in County Louth and the Blewitts in County Mayo.

These events may be more politically valuable to him in the US than his one engagement in Northern Ireland, given the power-sharing paralysis at Stormont.

While there is some disappointment that Mr Biden won't be staying in Northern Ireland for long, most politicians, business leaders and civic groups make the point that to have a presidential visit at all is a boon.

1 year ago

19

1 year ago

19

English (US)

English (US)