ARTICLE AD BOX

Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty Images

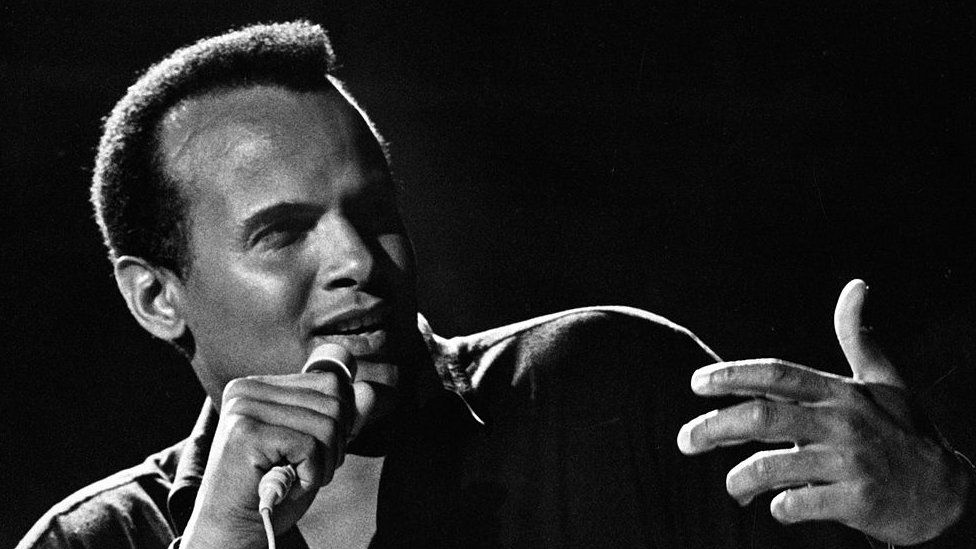

Harry Belafonte, who has died at the age of 96, was far more than just the "Calypso King".

He was a passionate civil rights activist who struggled to end segregation and a close confidant of Martin Luther King and Nelson Mandela.

He was also the star of films that challenged racist boundaries and dated stereotypes; an entertainer blacklisted in the savage, suspicious frenzy of McCarthyism.

When the US music industry needed a legend to bring its super-egos together for 1985 charity single We Are The World, it was Belafonte who had the credibility and the respect to make it happen.

Yet he remained charming and self-deprecating to a fault, fond of observing that he was the world's greatest actor "based on the fact I've convinced so many people I'm a singer".

This came from the man with an Oscar and a fistful of Grammys; the artist who gave the world the first album to sell a million copies; the performer who could turn his talent to blues, folk, jazz, gospel and, of course, calypso alike.

An early promise

Born in Harlem on 1 March 1927, Harold George Bellanfanti Jr was the son of mixed-race West Indian immigrants. His racial lineage was complex.

"On both sides of my family, my aunts and uncles intermarried," he said. "If you could see my whole family congregated together, you would see every tonality of colour, from the darkest black, like my Uncle Hyne, to the ruddiest white, like my Uncle Eric - a Scotsman."

His mother Melvine was a housekeeper who worked long days and made him promise never to let injustice go unchallenged. "It stayed with me forever," he later recalled.

"Whenever I came upon opportunities that were not offered to us because of race, because of poverty, I always remembered her counsel. She faced a life of endless rejection. I just marvelled at the way in which she seemed to endure."

Image source, Getty Images

Image caption,He was known as the King of Calypso but was also talented at gospel, folk and jazz

As a boy, he was sent to live with his grandmother in Jamaica to escape the grinding hardship of the Depression. There, he attended a British-style boarding school while back home his parents quietly separated.

Belafonte returned to the US in his early teens and joined the US Navy in World War Two - although he never saw active service or left the American mainland.

From Jazz to Calypso

Demobbed, he married his first wife, Frances Margaret Byrd, scraped a living as a maintenance man, and began hanging round the American Negro Theatre in his native New York. At first, they gave him work shifting scenes. Then they threw him bit parts. Eventually, he was playing the lead.

He was given a part in a mixed race company alongside two other aspiring actors - Marlon Brando and Tony Curtis. The play included a song that caught the attention of local talent spotters and he was asked to do a set at a jazz club called the Royal Roost.

Thinking he'd be the only performer, he did a double take as he walked on stage and spotted the house band. Charlie Parker was waiting with saxophone. Miles Davis was dangling his trumpet. "I had to clear my throat about 90 times before I knew what key I was in," Belafonte recalled.

Parker was a huge inspiration "playing in an incredible time for civilisation, when culture was leaping ahead". Belafonte was hired on the spot but eventually decided jazz didn't suit. "There was little room for lyrics or story," he said. "I had to think exclusively in terms of vocal gymnastics."

Soon he was picking up a Tony Award for his part in the musical revue John Murray Anderson's Almanac. He also starred in the successful film musical Carmen Jones, although his voice was inexplicably overdubbed by an opera singer.

Image source, Getty Images

Image caption,Carmen Jones - starring Belafonte and Dorothy Dandridge - was an international hit in 1954

Then came Calypso. In 1956, the album became the first in US history to sell more than one million copies. It spent 31 weeks at the top of the Billboard charts and made Belafonte a household name.

The first track was Banana Boat Song, better known as Day-O in reference to its famous chorus. It is a traditional Jamaican folk tune - and thus not technically a calypso - sung from the point of view of dock workers loading fruit on to ships. "Daylight come and me wan' go home" became his anthem.

A string of successful albums followed. His Christmas hit Mary's Boy Child sold a million copies in Britain alone, and Frank Sinatra recruited him to play at President John F Kennedy's inauguration.

Film stardom

A series of TV specials cemented his popular appeal and gave him the chance to introduce new acts to US audiences. They included a bright new star from Greece, Nana Mouskouri, and a shuffling harmonica player that Belafonte thought had talent - Bob Dylan.

As an actor, Belafonte turned down the lead in a film version of Porgy and Bess because he objected to what he considered to be the racial stereotyping of the role. In 1957, he did appear as an aspiring politician who threatens the white ruling class in Island in the Sun, a movie about interracial romance on a fictional Caribbean island.

The relationship between Belafonte's character and the film's leading lady, Joan Fontaine, was hugely controversial in pre-civil rights America. The film was a major success but Fontaine had to endure hate mail for her performance. Some of it was from the Ku Klux Klan.

Image source, Getty Images

Image caption,Suggestions of a relationship between Fontaine and Belafonte's characters in Island in the Sun was controversial

Off screen, Belafonte fell for another of his co-stars, Joan Collins. The resulting affair coincided with the end of his marriage, but the relationship did not last. Soon after the film's release, he married for a second time, to former dancer Julie Robinson.

The coming of The Beatles was a turning point. Belafonte's style of music suddenly seemed dated and his record sales suffered.

Civil rights

He became increasingly involved in the civil rights movement. Blacklisted during the McCarthy era, he suffered racial taunts and refused to play in the American South, where segregation was in force.

He became close to singer Paul Robeson, who opposed colonialism in Africa as well as racial segregation in the US. He supported the Freedom Riders, who travelled on buses in the Southern states challenging racial discrimination, and he idolised Martin Luther King.

Belafonte supported Dr King financially - the legendary orator made only $8,000 a year as a preacher. He also stood bail when his idol was thrown in Birmingham City jail.

Image source, Getty Images

Image caption,Belafonte, with Martin Luther King, toured the US supporting the civil rights campaign

With his friend Sidney Poitier, he entertained crowds campaigning for civil rights and stumped up $60,000 for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, one of the major civil rights organisations.

When Petula Clark briefly touched Belafonte's arm during a TV special, the sponsors tried to cut the segment.

"I've always accepted the fact that there's a price to be paid for those who choose to step into the waters of social development, civil rights, fighting against racism," he later said.

"I would rather have not been blacklisted, and perhaps made enough money to get me a private plane - but if in order to achieve that end I have to sell my soul, the answer is no."

In later years, there was a memorable appearance on The Muppet Show, where he sang a spiritual with characters designed like African tribal masks. It became creator Jim Henson's favourite episode and Belafonte would later sing it at his memorial.

Mandela, Bush and Trump

In 1985, he was instrumental in organising the recording of We Are The World - with the cream of US singing and songwriting talent - in an effort to raise funds for famine relief in Africa. He was later appointed a goodwill ambassador for the United Nations Children's Fund.

Three years later, he hosted a concert at London's Wembley Stadium to mark Nelson Mandela's 70th birthday. Mandela later brought him to South Africa, where he lent his weight to a campaign to highlight the dangers of Aids. He married for a third and final time, to photographer Pamela Frank.

At various times, he opposed the US embargo on Cuba and its invasion of Grenada. He attacked black members of the Bush administration during the Iraq war, including Colin Powell and Condoleezza Rice, comparing them to subservient slaves in the home of a white master.

Powell blandly dismissed his remarks as "unfortunate". An incandescent Rice went further, retorting that: "I don't need Harry Belafonte to tell me what it means to be black."

Image source, Getty Images

Image caption,Belafonte hosted Nelson Mandela's 70th birthday celebrations

He claimed he failed to see much difference between the Bush government and the 9/11 hijackers: both in his opinion were terrorists. Convinced that global capitalism was a clear and present danger to individual freedom, he told the Venezuelan leader Hugo Chavez that thousands of Americans supported his revolution.

When the Oval Office gained its first black president, Belafonte held him to the same standard as he did the others - condemning Barack Obama for failing to devote sufficient attention to the suffering of the poor. When Donald Trump was elected, he instantly became co-chair of the Women's March on Washington.

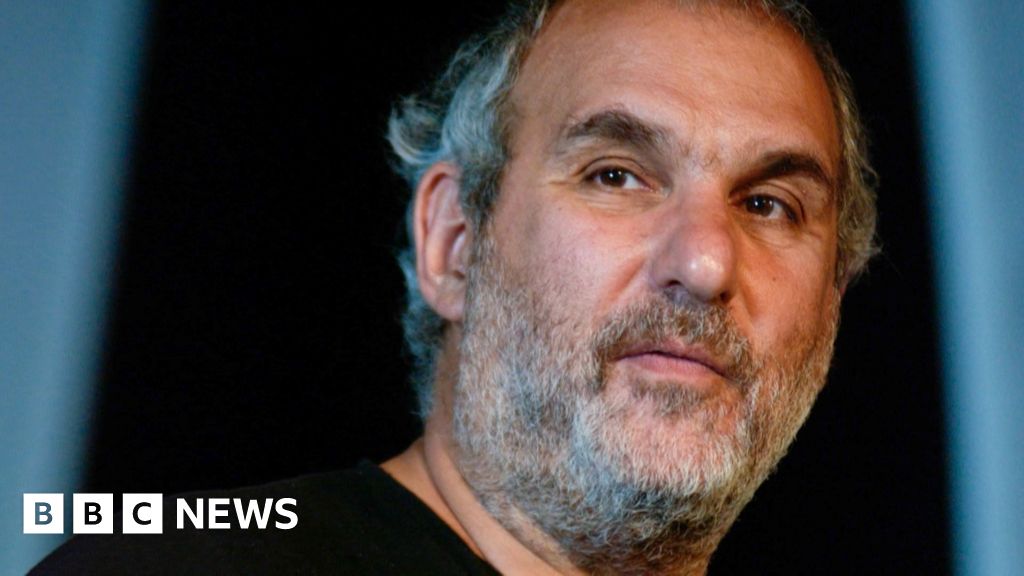

Belafonte remained a performer, film-maker and outspoken activist into his 10th decade. There were appearances alongside John Travolta in White Man's Burden and in Robert Altman's jazz-age drama Kansas City. In 2014, he was awarded an honorary Oscar for lifetime achievement.

In 2018, he made a dramatic cameo appearance in Spike Lee's film BlacKkKlansman as an elderly witness recalling a horrific lynching that took place in his childhood.

It is an extraordinary performance. The young black actors playing the audience are seen clinging to his every word in the knowledge that the character - and the man playing him - directly connect them to their grandparents' fight for civil rights and the legend of Dr King.

Image source, Getty Images

Belafonte will be remembered as a great entertainer who declined the temptation to sit back and enjoy the fruits of his good fortune. He campaigned as his mother had once directed: turning his fire on political and social injustice wherever he found it.

There were harsh words for those he thought stood in way of progress - which infuriated many. But there was also this wry admission that progress had been made, which perhaps contained a hint of pride in his own contribution to history.

"When I was born, I was coloured," he said. "I soon became a negro. Not long after that I was black. Most recently, I was African-American. It seems we are on a roll."

2 years ago

53

2 years ago

53

English (US) ·

English (US) ·