ARTICLE AD BOX

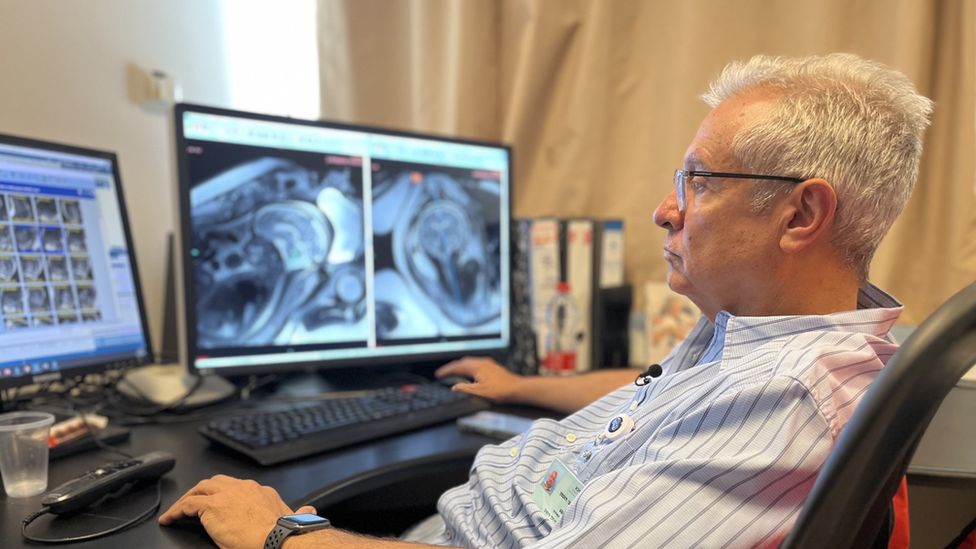

Relocation experts say most of those looking to emigrate are highly trained professionals like Professor Chen Hoffmann

By Yolande Knell

BBC News Middle East correspondent

As tens of thousands of Israelis continue to join weekly protests over the government's highly controversial plans to change the justice system, as many as one in three citizens are thinking of leaving the country, according to a poll.

Professor Chen Hofmann is one of them. Together with his wife and their children, they start the Jewish Sabbath with a meal together every Friday evening. Nowadays they end it at a huge anti-government rally.

"It's not our ritual to go and protest in the streets but we're forced to because we're losing our country, that's how we feel," says the doctor at the weekly Saturday night demonstration in central Tel Aviv.

The top Israeli radiologist is now moving to a hospital in the UK and is trying to persuade other members of his family, who all have European passports, to consider leaving.

"I'm going to London for a sabbatical, and this will be my laboratory to see if I can live outside Israel," he explains. "If the situation will be so bad, and it's worsening every day, we'll find a new place to live."

Among the crowds blowing horns and waving Israeli flags on Tel Aviv's Kaplan Street, there is fury at legislation being passed to limit the power of the Supreme Court.

Protesters believe it endangers democracy. However, Israel's hard-line governing coalition argues that its actions enhance democracy by fixing a judicial system in which elected politicians are too easily overruled.

Israeli protesters fear that a weakened Supreme Court won't be able to safeguard civil rights

While the demonstrators still hope new laws can be overturned, many admit that emigrating is something they, or those close to them, have thought about.

"It would be heart-breaking but I will not raise my kids in a country which is not democratic," says Sarah, a mother at the protest.

"If I can't be sure that my daughter's rights as a young woman are guaranteed, we will not stay here".

Israeli relocation experts say that in the past few months they have witnessed a spike in business. The expected negative economic fallout of the government's judicial changes and rising living costs are also push factors for those seeking to leave.

"We have seen a dramatic increase in the demand for information: we want to move to another country, how do we start the process?" says Shay Obazanek, CEO of one major firm, Ocean Relocation. "People with foreign passports who are able to move, ask for advice."

Ruth Nevo, a Portugal-based relocation specialist, has begun to see Israeli customers for the first time. "It's been absolutely insane, from none for years to like 25 inquiries a day," she says.

"And the people who are inquiring are very well educated. I'm talking about lawyers, judges, policemen, university lecturers, IT people; they're just very concerned about what's going on."

BBC

If I can't be sure that my daughter's rights as a young woman are guaranteed, we will not stay here.

International trends suggest that most people who look into emigrating for political reasons do not end up following through. Before and after the election of Donald Trump in 2016, many Americans who had initially threatened to move abroad abandoned their efforts.

However, in Israel, the recent political turmoil has opened up deep social divisions and raised alarm about shifting demographics.

The current coalition government relies on ultra-Orthodox Jews and religious nationalists who have socially conservative values and represent fast-growing parts of the population because of their relatively high birth rates.

Increasingly, as secular Israelis become a minority in the country, they see a threat to their liberal lifestyles. They now fear that the courts will no longer be able to protect their civil rights.

"What I think happened over the last six months, was a slow, incremental demographic process all of a sudden became extremely apparent," says Professor Alon Tal, head of the public policy department at Tel Aviv University.

He points out that secular Jews continue to shoulder the greatest share of the tax burden in Israel and do most of the compulsory military service, often spending years in reserves. The ultra-Orthodox community benefits from decades-old exemptions from the army.

Image source, Anadolu Agency

Image caption,Many of the people protesting consider themselves to be patriots and include military veterans and reservists

Professor Tal warns that an exodus, if it happens, could be devastating with a disproportionate impact on key sectors such as high tech, medicine and academia.

"When the truly talented people who carry on their shoulders the innovation and the economic development that this country is so dependent on, when they decide they've had enough and they don't want to live in a country that no longer represents them, then we could see a collapse, an economic collapse," he says.

At the Sheba Medical Center, just outside Tel Aviv, Professor Hoffmann is poring over the MRI scans of pregnant women. He is one of just four experts on foetal neuroradiology in Israel.

A new survey has just been published in which more than a third of young Israeli doctors and medical students said they planned to leave the country soon. The professor says he also knows a lot of experienced medics, like him, who are looking to head overseas and admits feeling conflicted.

"Even now we have a shortage of doctors," he notes. "So, if you know, even 5% will not come back, it will be a disaster."

Back at the weekly protests in central Tel Aviv, the national anthem plays out.

The demonstrators see themselves as dedicated patriots. Many are Israeli military veterans or reservists.

Some insist that whatever happens, they will never move away.

"I'm really worried but I'm staying because I feel solidarity," says Ruth, a physician who also comes to the protests each week and has previously worked in other countries.

"This is my responsibility to fight," she goes on. "This is like a second army service for me. We are like an army now."

Amid loud chants of "democracy", the fight continues at full volume to try to force the government to change track on its judicial overhaul.

But at the same time, another challenge is quietly building up, with more Israelis quietly drafting their exit plans.

1 year ago

13

1 year ago

13

English (US)

English (US)