ARTICLE AD BOX

Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty Images

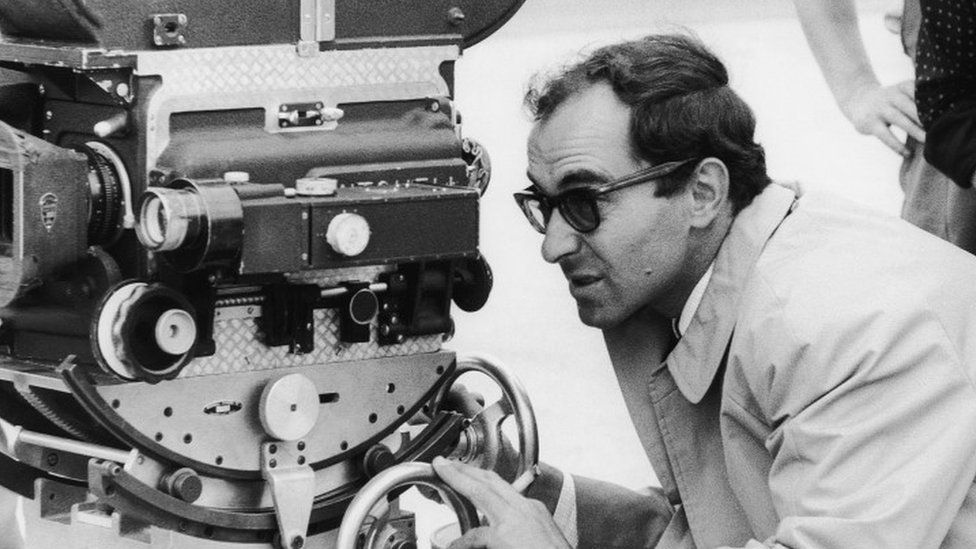

Godard on the set of Pierrot le Fou

Jean-Luc Godard, who has died aged 91, was one of the most influential directors in the history of cinema.

The French-Swiss filmmaker found fame in the late 1950s as one of the leading figures in the French movement known as the New Wave, going on to direct dozens of films in a career lasting more than half a century. Here are nine things to know.

1. He changed film with a girl and a gun

The girl, Patricia, is involved a with petty criminal, Michel, who is on the run for shooting a policeman. She betrays him and police shoot him dead in the street.

Breathless resembled a crime drama, but as with many of his works the plot was just a frame for Godard to explore culture, experiment with image, and examine cinema itself.

It had an instant impact, winning acclaim and a huge profit on its meagre budget.

Nearly 60 years on, it is widely acknowledged as a classic and its energy still startles.

2. He cut up convention

One of the most radical elements of Breathless was the prominent use of the editing technique known as the jump cut.

Filmmaking both before and after Godard's debut largely favours smooth editing to give the illusion of continuous time.

By contrast, in Breathless, Godard would cut within the shot, making time appear to jump forward.

Image source, Breathless

Image caption,Jump-cuts in Breathless: Godard edited within shots, causing the image to leap forward in time and space

It is jarring, as Godard surely intended it to be. At the very least it grabs the viewer's attention, but it has also been interpreted as reflecting Michel's boredom or as an attempt by Godard to force his audience to reflect on the nature of the cinema.

Throughout his career Godard would play with the grammar of filmmaking.

3. He rewrote the script

There were other innovations. Breathless was filmed on location, using handheld cameras, with Godard writing the script on the day, feeding lines to his actors as they filmed.

This was another break with tradition, with expensive studio-led films depending on tight scripts, large crews and storyboarding.

Image source, Getty Images

Image caption,Godard devised new ways of making films but they were a headache for others involved

The technique used by Godard gives Breathless great spontaneity and a documentary-like feel.

He would use it in many of his films, infuriating his stars who would turn up on set not yet knowing what their lines would be.

Godard and his New Wave contemporaries saw truly great films as being stamped with the vision of the director - and what better way to control a film if you are in effect making it up as you go along.

4. He was a huge cinephile

Godard might have been an iconoclast, but it came from a place of deep knowledge and affection for cinema.

Before becoming a director, he was an avid cinemagoer, sometimes watching the same film several times in one day at the clubs he and other New Wave figures attended.

In 2015, Raymond Cauchetier discussed his work photographing the glamour of French New Wave

Like other figures from the era, he was first a critic, developing his ideas of what he thought cinema should be that he was able to carry out in practice.

His films are littered with references to other works and even as he sought to push the medium forward he could not help but look back.

5. He kept innovating

Breathless alone would have secured his place in film history, but his has been a prolific career. The IMDB lists more than 100 works, including shorts, documentaries, TV series and more than 40 feature-length films.

The 1960s saw his most celebrated and widely watched works, from what he called a "neorealist musical", 1961's A Woman Is a Woman (Une femme est une femme) to the 1965 dystopian science-fiction Alphaville to 1967's black comedy, Weekend, featuring Emily Bronte being set on fire.

Image source, Getty Images

Image caption,Godard and Brigitte Bardot (R), who was the lead in his 1963 film Le Mépris (Contempt)

After Weekend he embraced political radicalism, making a series of Marxist-themed films that culminated in 1972's All's Well (Tout Va Bien).

In the decades that followed he retold the virgin birth, prompting a complaint from then-Pope John Paul II (Hail Mary), tried and failed to recruit Richard Nixon as an actor (King Lear) and released an epic personal history of film (Histoire(s) du cinéma). In 2014, while in his 80s, he released an experimental 3D film starring his dog Roxy (Goodbye to Language).

6. He made the audience work

There is no getting away from it - Godard's films range from the challenging to the near incomprehensible.

He has enjoyed commercial success but later works saw limited releases despite critical adoration.

Godard was a voracious reader on top of his love of cinema and the sheer weight of references can be bewildering, Barely 70 minutes long, Goodbye to Language, for example, packs in nods to abstract painter Nicolas de Staël, modernist US author William Faulkner and mathematician Laurent Schwartz.

Also at play is one of Godard's most important influences, German dramatist Bertolt Brecht.

Brecht wanted his audience to remain critically engaged in his work, and so deployed a number of methods to unsettle them and remind them they are watching something artificial.

Several of Godard's films use Brechtian devices, such as 1967's La Chinoise (The Chinese), which includes lurid captions and actors breaking the fourth wall, with Godard even leaving the clapper board in at the start of scenes.

7. He put himself in his art

In many of his works the lead can be seen as a proxy for Godard himself.

In 1963's Le Mépris (Contempt), Michel Piccoli plays a French playwright tasked with reworking a film adaptation of Ulysses.

The film explores the tensions between commercialism and creativity and portrays a disintegrating marriage, modelled on Godard's relationship with Anna Karina, the star of several of his films.

Image source, Getty Images

Image caption,Godard with Anne Wiazemsky, his former wife and star of several of his films

Characters in his film are often are a mouthpiece for himself but in later years he made himself a feature of his films.

In 1995 he made the autobiographical JLG/JLG - Self-Portrait in December and his essay films feature his own voice, most recently in 2018's The Image Book.

US critic Roger Ebert's assessment of Godard in 1969 described him as "deeply into his own universe", a good explanation of why Godard's films can be both so distinctive and so frustrating.

8. He could be a 'shit'

Not unjustifiably Godard has the reputation of being difficult both personally and professionally.

His two marriages, first to Anna Karina and then to Anne Wiazemsky, were stormy, something that spilt out into his films.

Angered by producer Iain Quarrier's recut of his 1968 Rolling Stones documentary Sympathy for the Devil, Godard punched him in the face when it was shown in London.

Image source, Getty Images

Image caption,The filming of Sympathy For the Devil, also known as One Plus One

There was an extraordinary row with his friend, another great New Wave director, François Truffaut.

In 1973, Godard wrote to Truffaut attacking his latest film, Day For Night, and asking for funds to make a response. Truffaut wrote a furious reply, accusing Godard of behaving "like a shit" and listing years of misconduct by Godard. Unsurprisingly, Truffaut refused to pay for Godard's film. The pair's relationship never recovered.

But collaboration was an important part of his career too.

His early films would not be the same without Karina or Wiazemsky, nor Godard surrogate Jean-Paul Belmondo.

He forged a close partnership with leftist thinker Jean-Pierre Gorin and cinematographer Raoul Coutard, who said: "He can be a shit... but he's a genius."

Since the 1970s his most important collaborator has been his life partner, the Swiss filmmaker Anne-Marie Miéville.

9. But he was also an inspiration

Film industries around the world saw their own New Waves. America's New Wave gave us works like Bonnie & Clyde, Chinatown and Jaws.

The work of Godard himself - whether personal, experimental, political or all three - has had a massive impact.

US director Quentin Tarantino named his production company A Band Apart, a reference to Godard's 1963 film Bande à part (Band of Outsiders). Italian director Bernardo Bertolucci included a homage to it in his film The Dreamers.

Godard's influence can be seen in the blurring of documentary and fiction by Iranian director Abbas Kiarostami or in the thematically and formally provocative work of Denmark's Lars Von Trier.

2 years ago

47

2 years ago

47

English (US)

English (US)