ARTICLE AD BOX

Image source, Alamy

Image source, Alamy

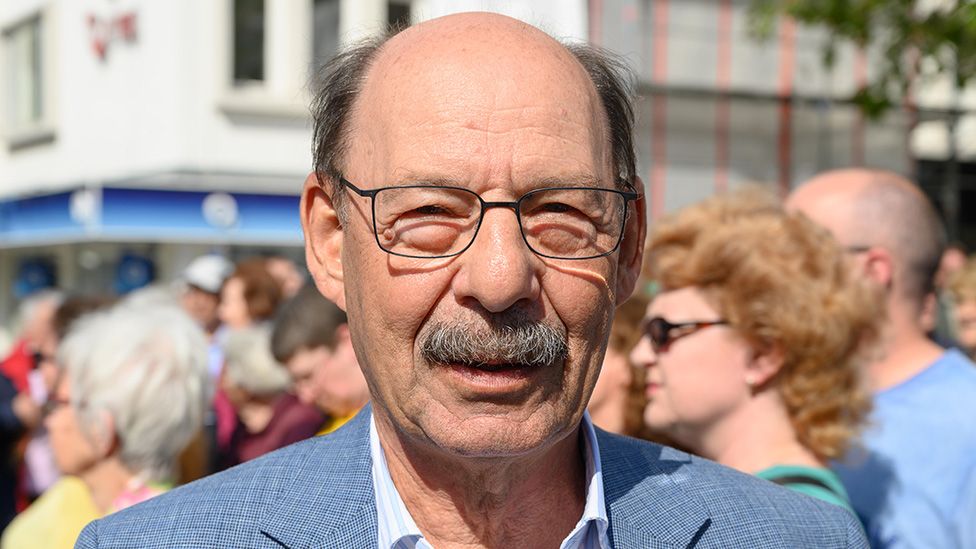

Michael Fürst says he was the first Jewish soldier to sign up with the German army after World War Two

"Captain, I would rather you didn't speak to me like that."

Choosing to stand up to your commanding officer as a new recruit is never a decision to be taken lightly. Even more so when you're the only Jewish member of the German Army, working alongside soldiers who fought under the Nazis in World War II.

Although decades have passed since Michael Fürst was on the receiving end of anti-Semitic comments, the sting is fresh in his memory, he tells BBC World Service's Heart and Soul programme.

"I had never heard anything like this before, never!" he exclaims.

Now 76, Michael is a lawyer and president of the Association of Jewish Communities of Lower Saxony. His office is lined with books that reflect these twin pillars of his life, along with medals and photographs.

Michael signed up to the German armed forces - the Bundeswehr - in 1966. He believes he was the first Jew to do so after World War Two. At the time, anyone in West Germany whose family had been persecuted by the Nazis was exempt from military service.

Two of Michael's grandparents perished in the concentration camps, but Michael was brought up with a sense of pride in his identity as both a German and a Jew. Joining the military was something that all his friends were doing on leaving school - and Michael saw no reason why he should not do the same.

"I was 19 years old, I was very sporty, and I didn't know what to do with my life," he remembers. "So there was only one decision: I would join the army like all the others."

Other Jews outside Michael's immediate circle found his choice hard to accept. "They called me the schmuck from Hanover," he laughs. "A stupid boy. And friends in the USA for example said: 'How can you go the army? How can you live in Germany?'

"It was a big thing to decide, whether you were more German or more Jewish. So I decided to be German and Jew."

'I am an anti-Semite'

During his two years in the Bundeswehr, Michael says he did not experience any anti-Semitism, apart from the remarks made on that sole occasion by his commanding officer. Clearly unsettled by the comments, Michael arranged a meeting with his captain the following day and asked to be moved to a different group.

"I'm glad you've come to see me, Fürst," said the captain. "I wanted to speak to you. I am an anti-Semite. My parents were sent during the Nazi time to the east of Germany, to make their new life there. And all the problems we had in that period came from the worldwide Jews."

Image source, Alamy

Image caption,Michael Fürst in uniform

Michael recalls, with a wry smile, his captain's attempt to win him over: "But I have no problem with you, Fürst. We can be good friends."

"Anyone who spoke like that today would be thrown out of the military immediately," says Michael. "But he returned to his old battalion. I reported it to the chief sergeant, who asked him: 'Is this true?' The captain nodded, the sergeant's eyes widened and his face turned pale. The next day I changed group."

Michael remembers serving alongside soldiers who still displayed their wartime medals with pride, including those with the infamous hooked cross. Today the use of such symbols is banned in anything other than very limited contexts, and punishable with a jail term.

"These soldiers would say that they struggled for Germany, they got this medal and they would never agree to put it away," he says. "I had no problem with them, and they had no problem with me as a Jew. But we had no discussion about Jews. It was not the time to discuss anti-Semitism. That came later, much later."

Michael Fürst and a number of Jews of a similar age have blazed a trail for others to join the Bundeswehr.

This new generation has also found themselves having to defend their career choice in the military.

Anne, 36, converted to Judaism as a teenager, and attended a Jewish high school in Germany which had strong links to Israel. We are not publishing her surname because of rules about identifying serving soldiers.

Her decision to become a soldier at the age of 15 was met with incredulity by her classmates and teachers.

"Why do you want to go to those who killed six million of us?" they asked her. The school principal suggested she work for the Red Cross. "I told her I don't want to go to a deployment and stand there without a weapon to defend myself and defend others," she says. "It didn't feel like that was my path."

So determined was Anne to join the German military that she researched the founding principles of the Bundeswehr to be in a better position to counter any challenge. "The Bundeswehr is an armed force that exists to defend values that we share as a society - protecting human rights, protecting the constitution, based on a free and democratic order," she says.

"When you understand how those values were violated by the Nazis, you can see that their armed forces were built on a completely different foundation. I was so thankful to live in a society based on the principles of the modern German constitution, and I wanted to protect that."

Johannes, a 24 year-old technician in the German air force, goes further. "There's a lot of cross-over between Jewish teachings and the values of the Bundeswehr," he argues.

"For example, in Jewish ethics, everyone has the right to self-defence. Defending our values, defending the German constitution, that is self-defence. So for me, being Jewish is very compatible with being a soldier."

It is perhaps a reflection of how younger Germans feel about the country's military past that Johannes did not even consider that joining the armed forces could be seen as an unusual choice for a Jew.

Today it is estimated there are around 300 Jewish serving personnel, many of whose families came to Germany following the break-up of the Soviet Union.

And as of two years ago, Jewish serving personnel have had the same access to religious pastoral care as Christian soldiers.

A modern-day Jewish military chaplaincy badge, with both Hebrew and German writing, and the star of David at the top.

It follows a historic agreement in 2019 between Germany's Central Council of Jews and the Ministry of Defence. Within the Bundeswehr there is now a Jewish chaplaincy with military rabbis who advocate for Jewish serving personnel and take care of their religious and spiritual needs.

The German military had Jewish chaplains in the past, but the tradition died out after World War I and was not revived. Today's military rabbis also offer voluntary classes to other members of the Bundeswehr to learn about Judaism.

Zsolt Balla, a Hungarian-born Jew, was installed in 2021 as the spiritual lead of the chaplaincy. He believes that the timing of his appointment and the creation of the military rabbinate reflects a shift in German attitudes towards Jews - a symbol, perhaps, of Germany's reckoning with its abhorrent past.

"I was born in Hungary in 1979, and I still remember what it meant to grow up in a Communist country in the 1980s," he explains.

"I won't say that history was overwritten exactly, but I saw how people never really managed to confront the wrongdoings and the terrible tendencies of WW2 and the Shoah [the Holocaust] in the way that Germany has.

"Maybe, just maybe, the reason why the agreement was made between the Jewish communities and the German Ministry of Defence is that we now reach the historical distance that enables us not to be paralysed by the past."

Image source, Bundeswehr

Image caption,Zsolt Balla (centre) meets soldiers in Germany

The ghosts of the past can still be sensed in many places however, and the spectre of anti-Semitism has not been banished from the German military altogether. Nazi memorabilia has been found in barracks in the past six years, and in 2020 online private networks were discovered sharing anti-Semitic language among soldiers.

"I'm asked very often about anti-Semitism," says Zsolt Balla, with a weary smile, "and my answer is that what we have to understand is that in any single armed force - not just in Germany - where people come voluntarily in, it drives people from the right side of the political spectrum. By definition.

"But for me, as long as the system says: we have a problem and we have to do something about it, I'm on board," he says.

"My job is about building bridges. Creating a Jewish chaplaincy is a really positive development. As Jews in the military, now we have an address. Now we know who to turn to if we have questions regarding Judaism. Many people in the Bundeswehr had never met a Jew in Germany, but now they can say they have. That's wonderful."

Michael Fürst is sceptical that the Bundeswehr needs quite so many military rabbis, given the relatively small number of Jewish soldiers - the aim is eventually to recruit 10 Jewish chaplains. But he acknowledges that the creation of the chaplaincy is a step in the right direction.

"Sure it's progress, and not only for Jews - for other religions too," he says.

"After I left the army, I worked hard to build a strong connection between Jews and the Bundeswehr. I was only a lieutenant, but I think I was the general of the Jews."

1 year ago

18

1 year ago

18

English (US)

English (US)