ARTICLE AD BOX

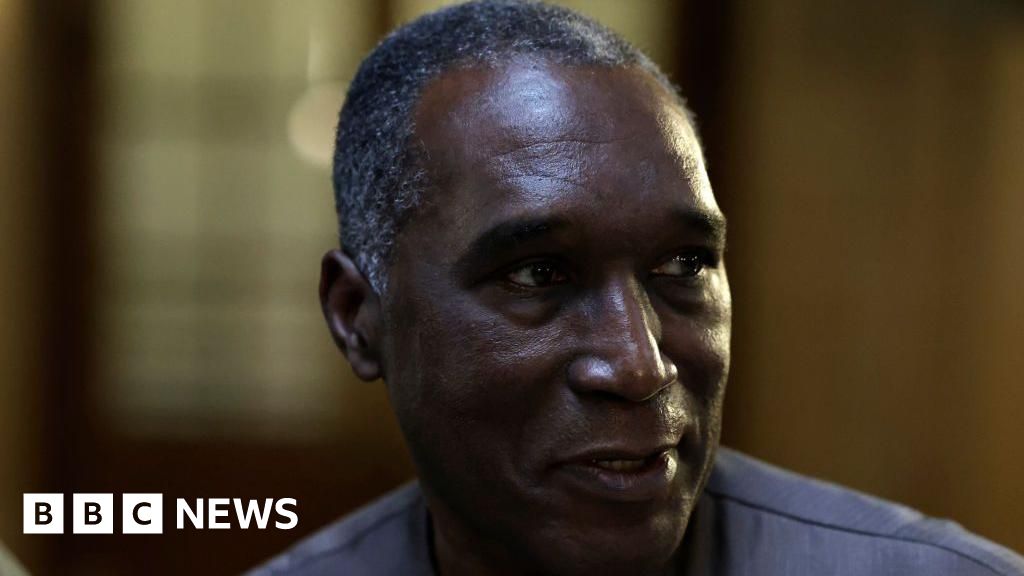

Mr Hamissa and his family escaped - but they have nowhere to go

By Samantha Granville

Johannesburg

Mussi Hamissa woke up to the sound of a massive roar. His bed was shaking and he heard people shouting: "Fire! Fire! Fire!"

In shock, he rubbed his eyes open to see the orange glow of flames coming into his makeshift apartment on the third floor of the building, formerly owned by the city of Johannesburg, that had become an informal home to migrants.

Mr Hamissa got his wife and their one-year-old baby out of bed. He realised that their only chance of survival was to jump out of the window.

So that is exactly what he did.

It was a rough landing on concrete and he is quite bruised. But he is alive.

Mr Hamissa's wife dropped their baby from the window and he caught him safely. His wife then tied a bed sheet to the satellite dish and shimmied down to the sidewalk.

"People started copying us. They jumped too, but they didn't make it," he said, eyes welling up.

"There were a lot of dead bodies... So many dead bodies. And I couldn't help them."

Mr Hamissa, from Tanzania, had lived in the building for three years. He knew all the other Tanzanians in the apartment block and said a lot of them did not make it out.

"I lost so many brothers and sisters. My family. They were all there, but I could only take my wife and baby."

The guilt would stay with him forever, he said.

The family also lost their money, passports and all their possessions.

Living in this building as a squatter, Mr Hamissa had not had to pay rent. And now with his important documents gone and a low-paying job, he's not sure what to do or where to go.

So he's sitting across the street from his home, smoke still rising from its shell, just hoping he has a roof for his son tonight.

"I don't know what they're going to do to us, but we don't know where it can go. The government should help us because we lost all of our things," he said.

Many were less fortunate than Mr Hamissa.

Sphiwe Ngcobo was outside the building at her street vending stand when the fire erupted. She said it happened so quickly that by the time she ran across the street to the building's entrance, the flames were already blocking the way.

She had two children inside - both on the second floor, both unreachable.

Ms Ngcobo waited for what felt like hours as people started to evacuate from the burning building.

Finally her five-year-old son was carried out by a neighbour. He was foaming at the mouth. He had inhaled so much smoke and was in such a state of shock that he was unable to stand on his own.

Ms Ngcobo does not know where her children, one of whom is dead, are

The paramedics took him to the hospital and she hasn't heard about his condition since.

Ms Ngcobo stayed behind, waiting at the scene of the fire for more information on where her two-year-old's body has been taken.

She wants to say goodbye, to have some closure.

"I don't know what to do, I don't know where to go," she said. "I don't know what hospital my child is in, and I don't know what mortuary my other child is in. So I'll wait here for news."

Mr Hamissa and Ms Ngobo were sitting in a group of about 50 people, all trying to get some sleep while they waited for officials to tell them what would happen.

There was a stench in the air of old smoke and expired food. The pavement was littered with garbage and unknown liquids.

For now, that's where they will be staying.

1 year ago

49

1 year ago

49

English (US)

English (US)