ARTICLE AD BOX

Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty Images

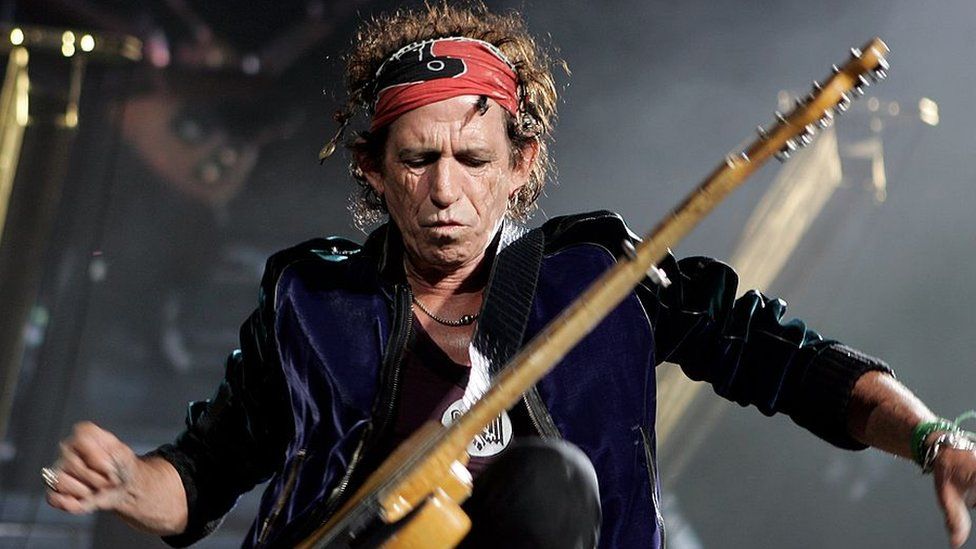

Keith Richards formed the Rolling Stones with Mick Jagger in 1962

By Mark Savage

BBC Music Correspondent

If there's one constant in the story of the Rolling Stones, it's Keith Richards' love affair with the guitar.

He owns more than a thousand of them - although he only plays a select few on stage - and, even as he approaches 80, the star is still bewitched by the instrument.

"The fascinating thing is that the more you play it, the less you know it," he says. "It provides you with endless questions. You can never know the whole thing. It's impossible."

He's back on fiery form on the Rolling Stones' new album, Hackney Diamonds. There are hard-rocking riffs (Angry, Depending On You), sinewy country blues (Dreamy Skies) and semi-improvised gospel stomps (Sweet Sounds Of Heaven).

But while the Stones sound ageless as ever, Richards' hands are gnarled with arthritis. Has it affected his playing?

"Funnily enough, I've no doubt it has, but I don't have any pain, it's a sort of benign version," he says. "I think if I've slowed down a little bit it's probably due more to age.

"And also, I found that interesting, when I'm like, 'I can't quite do that anymore,' the guitar will show me there's another way of doing it. Some finger will go one space different and a whole new door opens.

"And so you're always learning. You never finish school, man."

Image source, Getty Images

Image caption,Keith Richards with a small selection of guitars - he owns more than 1,000 in total

Hackney Diamonds is the Rolling Stones' first album of new material in 18 years. Not that they'd been resting on their laurels. Sessions had come and gone, tours had been staged, a covers album released. But, for whatever reason, the band weren't happy with the material.

"There's a lot of stuff in the can which is pretty damn good," says Keith, "but it's not an album. It's just a lot of tracks."

The turning point came at the end of the band's 60th anniversary tour last year. Rather than retreat to their individual bunkers, Mick Jagger wanted to go straight to the studio.

"He hit me in the right spot," says Richards. "I've always wanted to record the band as soon after we get off of the road, because the band is lubricated."

Where previous sessions had been exploratory and unfocused, these recordings came with a deadline: Jagger wanted the basic tracks finished by the end of the year.

He was helped by producer Andrew Watt, a 32-year-old who has made pop hits for Post Malone and Miley Cyrus, and overseen grizzled rock rebirths for Iggy Pop and Ozzy Osbourne.

A massive Rolling Stones fan (he wore a different band t-shirt every day), he was nonetheless determined not to defer to his heroes.

"We had a referee, which is something we lacked since the Jimmy Miller days," says Ronnie Wood, referring to the producer of 1970s classics like Sticky Fingers and Exile On Main Street (both of which pre-date his time in the band).

"We needed someone tightening up and kicking us. He disciplined us and said, 'Come on, you're not going to do that tomorrow, you're going to do it today'."

"I can understand Ronnie seeing it that way but the real referees are Mick and me," argues Richards.

"Andrew just had the right amount of energy and the right amount of know-how to pull it off."

Fortuitous meeting

Jagger and Richards have always been the lifeblood of the Rolling Stones. Or, more accurately, its Id and its Ego. Jagger is watchful, analytical, strategic. Richards runs on instinct.

They first met at primary school in Kent in the 1950s, then bumped into each other years later on a railway platform. Jagger was carrying a bundle of records, Richards was holding his guitar, and the two struck up a conversation about rock and blues on the train.

Within a year, they'd formed a band, and Richards wrote excitedly to his aunt: "Mick is the greatest R&B singer this side of the Atlantic and I don't mean maybe."

Initially, the Stones were a cover band, scoring hits with scuffed-up versions of Buddy Holly's Not Fade Away and Howlin' Wolf's Little Red Rooster.

But their manager, Andrew Loog Oldham, realised everyone would make more money if they wrote their own songs, so he locked Jagger and Richards in a kitchen and told them not to come out until they'd got a hit.

The result was As Tears Go By, which was taken into the charts by Marianne Faithfull.

"Before that, I thought of songwriting as a totally separate job - like there's the blacksmith, and there's the stonemason," Richards later recalled.

"It was a shock, this fresh world of writing our own material, this discovery that I had a gift that I had no idea existed. It was Blake-like, a revelation, an epiphany."

Jagger disputes the kitchen story but, either way, one of rock's greatest songwriting partnerships had been born.

By the end of the decade, the duo had written dozens of classics, including Paint It Black, Sympathy For The Devil and (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction, the riff for which came to Richards in his sleep.

"It was a lucky find, I must admit," he told me the last time we spoke.

The Rolling Stones at Top Of The Pops in 1962 (clockwise from top left): Bill Wyman, Brian Jones, Keith Richards. Charlie Watts and Mick Jagger

The sessions for Hackney Diamonds captured the hit-and-run sessions of the 1960s. The band cut two or three songs a day, often playing next to each other as they do on stage.

The whole process was finished in two months - eight times longer than they spent on their 1964 debut, but still phenomenally fast by modern standards.

The album's title is London slang (Hackney Diamonds are the beads of shattered glass strewn across the street after a smash-and-grab) and while it doesn't appear in the lyrics, the phrase pinpoints the album's untamed ferocity.

"If I was a dog, I'd spend all night howling round your house," growls Jagger over the saw-tooth riff of Bite My Head Off.

Even the song titles suggest a deep well of antagonism and resentment: Angry, Driving Me Too Hard, Live By The Sword.

Richards can't or won't explain the inspiration, arguing that "Mick writes the lyrics".

"But he's got some angst in him and I said, 'Well, let's use it'," he adds.

"From my point of view, the essential thing about making a record is that the singer has to want to sing the material.

"Mick, given a song that he's not interested in, can really make it bad. And that's maybe one of the reasons it took 18 years, because Mick's waves of enthusiasm come and go."

Image source, Universal Music Group

Image caption,The Stones line-up of 2023: Ronnie Woods, Mick Jagger and Keith Richards

If that's a dig at his bandmate, its meant jovially.

The bitterness that characterised their relationship in the 80s has evaporated. For this album, they even went back to basics, writing Driving Me Too Hard together in the same room.

Jagger says they still disagree occasionally, but have "a good understanding" of what the Stones' represent. For Richards, it's all a state of mind.

"We're very real guys, so when we start playing we all know, 'Yep, that's it', or 'No, that isn't it'.

"And if it feels phoney, then we have to watch ourselves."

That's why he resisted Jagger's attempts to steer the band towards punk and disco in the 1970s; and presumably why they've steered clear of more reflective material on this album.

But the record did present an unwelcome challenge: Recording for the first time without Charlie Watts, their stoic and dependable drummer, who died in 2021.

His playing features on just two Hackney Diamonds tracks, Mess It Up and Live By The Sword, initially recorded in 2019. For the rest, the rhythm section is provided by Steve Jordan, who Watts had anointed as his successor.

"I was with Charlie before he passed and he said, 'Make sure Steve Jordan covers for me. He has my blessing'," says Wood. "So that was a real comforting thing."

"Feeling like I'm carrying on Charlie's wishes makes it a little bit easier," agrees Richards.

"I will always miss the man dearly, but I know that if he was here today, he would be very happy to know that the band was continuing."

Image source, Getty Images

Image caption,Charlie Watts died in 2021, prior to the band's 60th anniversary tour, after suffering from throat cancer

Elsewhere, the album has a glut of superstar guests, including Paul McCartney, Elton John and erstwhile Stones bassist Bill Wyman.

But the star attraction is Lady Gaga, who trades vocal hooks with Jagger on the soaring blues-gospel of Sweet Sounds Of Heaven.

"Lady Gaga is a piece of work," says Richards. "I love working with her because she has a great attitude and a great voice, and I always wanted to see her play off against Mick."

"Stevie Wonder is on there as well, which is sort of thing only happens when you record in LA," he laughs, noting that the song was "very ad-libbed... it even finishes and starts up again".

That was their approach throughout. The whole album is deliberately hand-crafted, recorded in real-time and non-computerised.

"I like real," says Richards."We actually cut this record primarily for vinyl. It's by far the best sound, if you want to listen to a record properly.

"Digital is toy town. It's synthesizers. And now you have AI, which is even even more superficial and artificial. Vinyl gives you what's real and I prefer to hear it that way."

The last track is the perfect example - just Mick and Keith standing around a microphone, riffing on the Muddy Waters' song that gave the band its name, Rolling Stone Blues.

It could be the closing of a book, an epilogue to a 60-year career, but Richards is having none of it.

"It's a fitting statement, but it's not a coda," he protests. "It's more a tip of the hat to Muddy Waters, Chicago and all the blues men we learned our stuff from."

Image source, Getty Images

Image caption,Keith Richards will be 80 when the band goes on tour next year

In fact, rather than waving goodbye, the band are plotting to take their new music on the road next year, "if everybody is still standing".

"We're all in good fettle," says Richards. "We're not looking at each other and saying, 'time's up'.

Is that a phrase he could ever imagine uttering?

"My answer is I'm not Nostradamus," he chuckles. "Of course it's going to end some time, but there's no particular rush.

"We're having great fun doing this."

1 year ago

33

1 year ago

33

English (US) ·

English (US) ·