ARTICLE AD BOX

By Joice Etutu

BBC News, Malindi

Immaculate Wiziri, overcome by grief at the death of her partner, feels abandoned by the Kenyan police force where he was so proud to work.

Her childhood sweetheart Jacob Masha, 32, took his own life in January - while off-duty with a police-issue weapon.

But as he died through suicide and not in the line of duty, the police have not offered her counselling or any help to the struggling family.

The BBC asked the police for comment, but they did not respond.

Since having their first child in 2007, the couple had lived together in the coastal town of Malindi.

Like thousands of police officers in Kenya, Masha struggled with his mental health.

Yet he did not confide in family or friends about the his problems and the pressures of work in the force, which he joined after leaving school aged 18.

Immaculate Wiziri tries to hide her grief from her children

Looking back, Wiziri says he did occasionally mention being exhausted.

"Sometimes he would tell me and say things were tight at work, that he didn't even have time to rest," she says.

"That it [his job] was too demanding, and he was back-to-back work. I used to advise him to take heart because some day you'll get something better."

But policing had always been his dream, right from the time they met aged 15.

"For as long as I can remember, that's all he spoke about. I was proud of him and supported his decision," she says, fighting back the tears.

Stress, trauma and brutality

It seems the Kenyan police force recognises it has a problem - earlier this year the police chief said nearly 2,000 of his officers were found to be unfit to serve because of their mental health - out of a total force of about 100,000.

According to the latest statistics, there were 57 police suicides last year. So far this year, there has been at least one suicide each month, with some months like April seeing several suicides in a single week.

Demas Kiprono

Policing is considered a very macho profession and expressing your feelings is considered a form of weakness"

Data before 2021 has not been made available, but anecdotally the problem appears to be growing and may explain why the police has set up a task force to improve mental health amongst officers.

As well as offering counselling sessions, it wants to encourage a culture where colleagues can open up to each other if they are feeling down.

Demas Kiprono, a campaign manager at Amnesty Kenya who has been researching police mental health for the past four years, welcomes the move.

"Policing is considered a very macho profession and expressing your feelings is considered a form of weakness.

"This culture has bred a situation where they [police officers] feel trapped and that may cause them to use the firearms given by the government against themselves or other members of the public."

This is echoed by psychologist Rechael Mbugwa, who has treated dozens of police officers at her practice.

"For officers, seeking help is seen as a sign of weakness. They're the ones people turn to for help so how can they now appear helpless?"

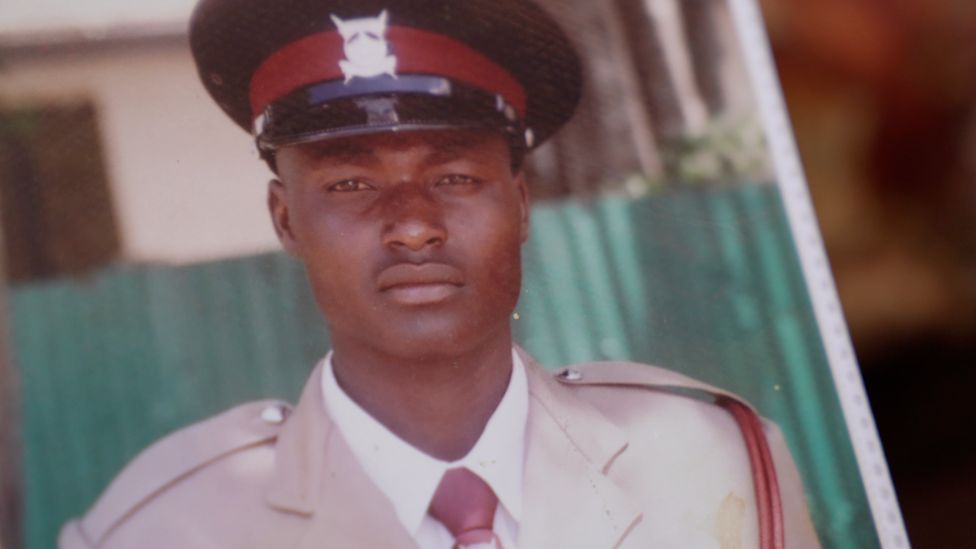

From a young age, Jacob Masha had always wanted to join the police

Mbugwa explains police officers often become numb themselves in order to cope: "The kind of work they do has high stress and is very traumatic.

"The spectrum of cases which police have to deal with is extreme - one day it's a traffic issue, another day it's an accident, the next it's violence and another day children are being violated. It's a lot to deal with."

Kiprono sees a link between mental health problems within the force and rising cases of police brutality.

In April, Amnesty Kenya collaborated with Missing Voice, a network of local non-governmental organisations, releasing a report that found an increase in the number of police brutality cases.

They document how officers have beaten people to the point of unconsciousness, robbed civilians and even shot and killed innocent people.

The numbers are startling:

- 2019: 145 cases of police killings

- 2020: 168 cases of police killings and/or enforced disappearances

- 2021: 219 cases of police killings and/or enforced disappearances.

"When officers are not well in their minds, they will use the public as outlets, and you notice a rise in police brutality," says Kiprono.

"So, it is within our interest to ensure police welfare [and] police human recourse is taken care of so that they can take care of the safety and human rights of the people of Kenya."

'Survival of the fittest'

The strain officers are under is all too clear to see in a photo album left behind by Masha.

Scrawled on one taken during his training days are the words "survival of the fittest" - underlying how strenuous their manoeuvres were.

Immaculate Wiziri does the odd tailoring job to try and get money to feed the family

The back of another explains how the shot was taken when he was exhausted after trekking 50km (35 miles) through forest chasing thieves who had stolen "400 cows, 500 goats, five donkeys, 40 camels and five women".

He goes on to say that they managed to eventually arrest them after "walking for 300km day and night" in Pokot, a cattle-rustling region in western Kenya near the border with Uganda.

As Wiziri flicks through the album, her bewilderment is unmistakable. At times she stares aimlessly into the distance unable to fathom what has happened.

At other times she is inconsolable, but she puts on a brave face in front of her two young children.

Following Masha's death she has been doing small tailoring jobs - the family have had to skip meals at times, and she has no money for private counselling.

James Masha did not explain why he took his life

"Since it happened, I don't know who to go to - he was all I had. He helped with everything I did. I don't have anyone to advise me, there is no-one to hold my hand. I do everything by myself."

The 32-year-old is distraught that the help now being offered by the police did not come soon enough for her partner.

But she hopes that the new awareness campaign will mean that they will reconsider her case - and those of the families of others officers who have taken their own lives - and offer her counselling and financial help.

2 years ago

20

2 years ago

20

English (US)

English (US)