ARTICLE AD BOX

By Paul Glynn

Entertainment & arts reporter

image source, Alex Lake

image captionThe Manic Street Preachers are Nicky Wire (centre), James Dean Bradfield (left) and Sean MooreThe Manic Street Preachers found themselves at a traumatic crossroads in 1995.

Anarchic lyricist Richey Edwards, who along with bass player Nicky Wire had been the chief songwriter behind their most recent and most iconoclastic album, 1994's The Holy Bible, was suddenly missing.

The post-punk rockers had previously played without Edwards at a festival when he had checked into The Priory due to problems with alcoholism and self-harming (he once carved the words "4 Real" into his arm with a knife for the benefit of NME journalist Steve Lamacq).

But the prospect of going on without him while an investigation into his disappearance was ongoing was another matter entirely.

Then, about six months after Edwards went missing, a new song changed all that.

"A Design For Life saved us," recalls frontman and guitarist James Dean Bradfield.

"We were like, 'Well, we don't know if Richey would even want to be part of this band any more, but we think he may have liked this song'. And that made us go forward."

Edwards was never found, but after many false trails and rumoured sightings he was legally declared dead in 2008, a fact some still question. For years, the Manics continued to pay royalties to his estate, and left an empty microphone on stage in the hope that their backing vocalist and childhood friend would return.

Meanwhile, A Design For Life, an anthemic string-laden dissection of working class life in the UK, raised his band up from cult heroes to part of the mainstream Britpop landscape. While supporting Oasis at the era's defining concert at Knebworth in 1996, the Manics closed their set with the track, which appeared alongside five contributions from Edwards on their Brit Award-winning fourth album Everything Must Go.

"We were just coming out of our own trauma at that point," Bradfield continues. "Design for Life was proving to be something that kept us going as a band, that validated us, that took us past the procedure of not knowing whether we could be in the Manics any more.

"It kind of solved a lot of really awkward emotional riddles for us. We were on our way to something, reaffirming ourselves and and staving off having to think about really serious, damaging things with regards to Richey and his family."

'Snow globe moment'

A Design for Life is what Bradfield describes as a "Trojan horse Manics" tune - using epic radio-friendly rock to carry a political message.

Using similar tactics, they managed to subsequently smuggle If You Tolerate This Your Children Will Be Next and The Masses Against the Classes to the top of the UK singles chart. (The former tackled the Spanish Civil War, while the latter contained quotes from both Noam Chomsky and Albert Camus.)

On their 14th and latest album, their trademark big guitar sound has been largely replaced by Abba-inspired, piano-driven pop melodies. Bradfield, the band's main musical force, learned to play piano properly in lockdown after inheriting one from another Edwards - a 105-year-old Mrs Edwards in Cardiff.

"It felt like a special gift being stowed upon us", he says. And he soon began to find new joy in the old chords.

"I had that lovely experience on the piano of just tooling around and going, 'Oh my God, I have to call Billy Joel. If the band don't want this he will!'" he laughs.

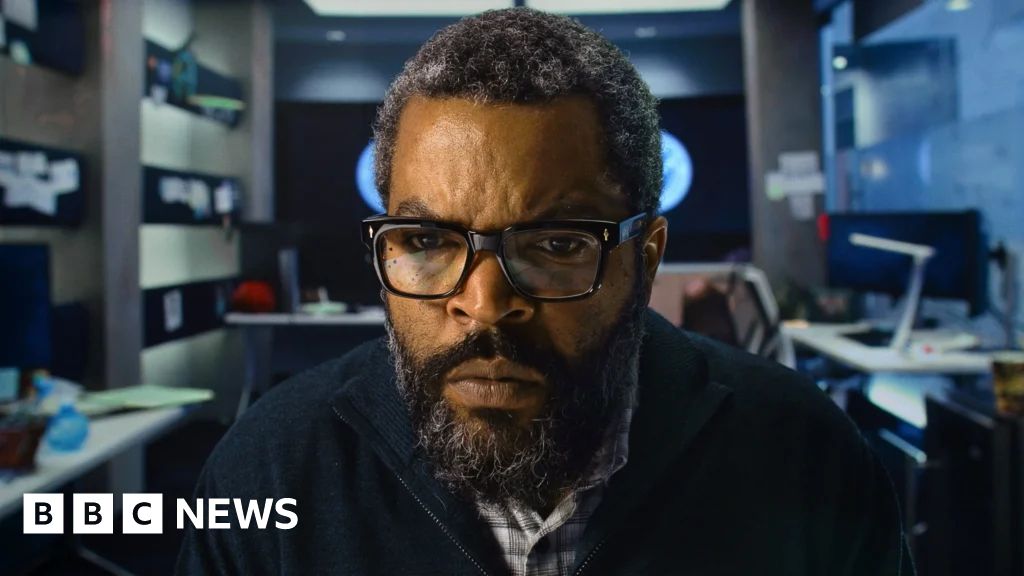

image source, Alex Lake

image captionA Design for Life for was only narrowly kept off top spot by Mark Morrison's Return of the MackRecorded between lockdowns at their own new studio in Newport, as well as the famous Rockfield, the album feels like a "snow globe moment", the singer says. "Everything felt like a living, waking dream. Sometimes you were writing music to try and prove that life still worked in the same way."

Hidden within the dreamy new pop packaging though, as ever, is a pointed message from the pen of wordsmith Wire. Lead single Orwellian finds the band waking up in a dystopian future where the political waters are muddied - "We live in Orwellian times / It feels impossible to pick a side" - and language is deliberately misused by those in power - "Words wage war, meanings being missed / I'll walk you through the apocalypse".

"It's about how language can be reordered then appropriated to accuse or to justify to build or destroy," Bradfield explains.

"I would say that the people who appear to govern from the middle ground, when they get up every morning and they see the culture wars raging around them, they go, 'Yeah, they're still fighting amongst each other, we'll still be in government for the next 10 years.' That's the way I see it."

Back in the day, the Manics weren't adverse to some wicked wordplay. Edwards once said they would "always hate [shoegaze band] Slowdive more than Hitler". Bradfield feels that sort of tongue-in-cheek vitriol, which used to be "part of the dance" of being in band, has now gone out of music and moved into daily modern life, but in a far more "egregious" way.

"Genres bleed into each other [these days] so music is less tribal, but culture is more tribal," Bradfield states.

One damaging effect of the culture wars, he adds, is that "people that should loosely be on the same side can't be on the same side". The veteran rocker thinks the "confusing" times also make it more difficult for young bands to write politically-charged anthems than it was when the "naturally angry" Manics formed in 1986, fuelled by the very clear "storm outside our window" - a reference to the miners' strikes.

image source, Getty Images

image captionThe band will perform a gig for NHS workers in Cardiff later this month, and tour the UK in OctoberWhen BBC News caught up with the band several years ago, they were Wire-less, with the bass player missing their Biggest Weekend headline set in Belfast due to his mother being terminally ill, and sadly now gone.

The spectre of death and the shadow of their missing bandmate Edwards hangs over this album on tracks like opener Snowing in Sapporo and closer Afterending, while Diapause is a reflection on our recently enforced hibernation.

On the LP's second single, The Secret He Had Missed, which tells the story of the sibling artists Gwen and Augustus John, Bradfield duets with Julia Cumming of New York band Sunflower Bean. Another guest, Mark Lanegan of Screaming Trees fame, joins them for the ominous yet fragile Blank Diary Entry.

image source, Getty Images

image caption(Left to right) Richey Edwards, Nicky Wire and James Dean Bradfield performing in 1991 before the release of the Manics' debut album Generation TerroristsAll now in their early 50s, Bradfield jokes that the members of the Manics are less like their heroes The Clash, Iggy Pop, Public Enemy or Guns N' Roses, and more like the Last of the Summer Wine gang these days.

Their stance on their early band manifesto, which stated they would never write a love song, has softened slightly. "As you get older, you realise that sometimes all there is is love," he admits. "It's the only thing that saves you sometimes... You don't know that when you're 16."

Now in 2021, the elder statesmen of Britpop seem to have arrived at another crossroads.

"It feels increasingly hard for us to commit to playing Holy Bible songs as a band," Bradfield reveals. "You have to be very physical. You have to train yourself to play that music. It really is quite intense.

"It's not a closed chapter," he adds, leaving the door ajar to playing their earlier Edwards-era material. "But there are not many more ways you can investigate what happened with Richey and what we experienced with him.

"I don't really think we want to look that deeply into things any more because we've looked there a million times and there are no answers."

Manic Street Preacher's album The Ultra Vivid Lament is out now.

4 years ago

103

4 years ago

103

English (US) ·

English (US) ·