ARTICLE AD BOX

By James Gallagher

Health and science correspondent, reporting from Porton Down

One of the UK's most secretive centres of scientific research - Porton Down - is aiming to stop the next pandemic "in its tracks".

I have passed through the incredibly tight security at this remote facility to get rare access to its scientists.

They are based in the shiny new Vaccine Development and Evaluation Centre.

Their work builds on the response to Covid, and aims to save lives and minimise the need for lockdowns when a new disease next emerges.

"Covid, of course, is not a one-off," says Prof Dame Jenny Harries, chief executive of the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA), which runs these laboratories.

"We say it [Covid] was the biggest public health incident for a century, but I don't think any of us think it'll be a century before the next," she adds.

The combination of climate change, urbanisation and people living closer to animals - the source of many new diseases which transfer to people - means we're facing a "rising tide of risk", she says.

Dame Jenny Harries is clear Covid was not "a one-off" public health incident

Porton Down - located in the tranquil Wiltshire countryside, near Salisbury - is one of the few places in the world equipped to research some of the nastiest viruses and bacteria you could imagine. The freezers here contain the likes of Ebola.

Neighbouring buildings include the Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (part of the Ministry of Defence), where it was confirmed the nerve agent Novichok has been used in the Salisbury poisonings.

The vaccine laboratories - housed in dark green buildings - were hastily constructed as part of the emergency response to Covid.

But, as the intense demands of the pandemic have waned, the focus has shifted.

The new vaccine research centre is concentrating on three types of threat:

- known infections that are getting harder to deal with, such as antibiotic-resistant superbugs

- potential threats that might cause a problem, including bird flu and new Covid variants

- and "Disease X" - something unforeseen, like Covid, which takes the world by complete surprise

The aim is to work with the pharmaceutical industry, scientists and doctors to support all stages of vaccine development.

Porton Down scientists are working on the first vaccine against Crimean-Congo Haemorrhagic Fever, which is spread by ticks and kills around a third of those infected.

The disease is found in Africa, the Balkans, the Middle East and in Asia - and could spread further with climate change.

At the other end of the process, vaccine effectiveness is evaluated. It was scientists here who spotted that the Omicron variant could bypass some of the protection afforded by Covid vaccines.

And they are still monitoring new Covid variants by growing them in the laboratory, exposing them to antibodies in taken from blood samples and seeing if new variants are still able to infect.

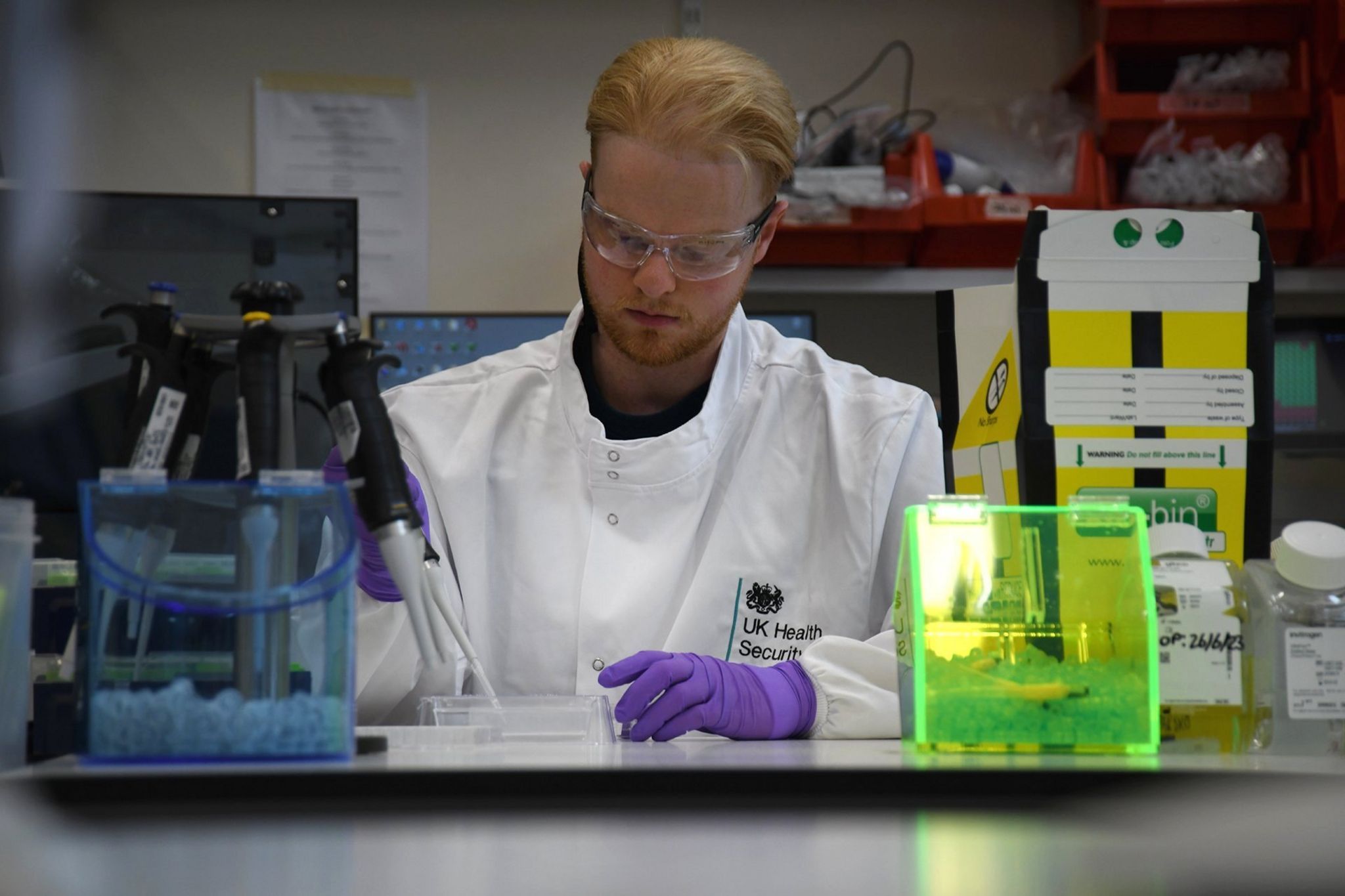

Antibodies taken from blood samples are being tested at the lab to see if they still offer protection against new Covid variants

Meanwhile machines - unofficially named Qui-Gon, Obi-Wan, BB8 and Palpatine - are part of the front line monitoring the threat posed by the world's largest flu outbreak in birds.

The H5N1 avian flu virus has devastated bird populations, and routine testing of farmworkers has found the first, symptomless, cases in people in the UK.

The difference is, before the pandemic the teams here were able to test just 100 samples a week - now it's more than 3,000.

Faster vaccines

The work here feeds into the "100 Days Mission" - a hugely ambitious vision to develop a vaccine against a new threat in 100 days.

Historically, it has taken a decade to design and test new vaccines. The unique circumstances of the pandemic meant the first Covid vaccines were produced within a year, with the vaccine rollout starting in December 2020.

Estimates suggest Covid vaccines saved more than 14 million lives in just the first 12 months they were used.

"Imagine if those vaccines had been available just a bit earlier," said Prof Isabel Oliver, chief scientific officer for UKHSA.

"They were available more rapidly than ever before in history, [but] we could have saved many more lives and we could have returned to greater normality much more quickly."

The hope here is the lessons of the Covid pandemic will be mean we are better prepared next time.

Prof Harries says in the past we have been simply reacting to events, but in the future we need to be on the front foot and "try and stop" any pandemic before it even begins.

And if a new disease does occur, she adds, we need to "stop it in its tracks" in its earliest stage.

1 year ago

120

1 year ago

120

English (US) ·

English (US) ·