ARTICLE AD BOX

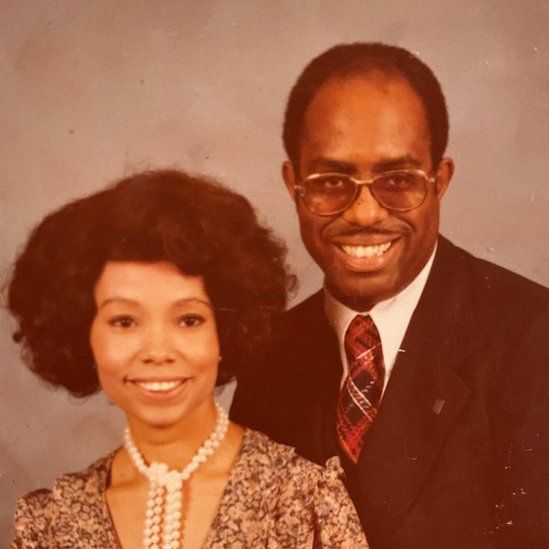

Image source, Louis Weathers

Image source, Louis Weathers

When Louis Weathers and his wife were looking for a house in the 1950s, they were only shown property in the majority-black area of Evanston

By Mike Wendling

BBC News, Evanston

Evanston, Illinois, is a quiet place in the middle of an unusual experiment.

In this university town just north of Chicago, a sheen of affluence glints through the windows of solid brick buildings downtown, while rainbow flags and "Black Lives Matter" placards dot what seems like every other suburban lawn.

Its population of 78,000 is diverse - about two-thirds white, nearly a fifth black, with sizeable Asian and Hispanic communities - and its politics, predictably, liberal. During the 2020 election, Donald Trump got less than a tenth of the vote here.

But like other places across the country, Evanston is dealing with a legacy of racial inequality stemming from slavery and segregation.

While some places, like California, are discussing reparations to make amends for slavery, Evanston's approach has zeroed in on a related but more recent injustice: discrimination against black citizens when it comes to buying a home.

The city has started paying money to black residents who faced barriers to buying the home they wanted due to mid-20th Century policies - the first US city to do so.

Recipients are delighted - but not everyone agrees about whether this is truly justice.

Image source, Getty Images

Image caption,Evanston's political scene is reliably progressive. Local politicians say this made passing a reparations bill possible

What are reparations?

The idea that America owes something to its black residents - some of whom were slaves, and some of whom have continued to suffer from the repercussions of racism - has existed for centuries.

In the 18th Century, a slave from Ghana named Belinda Royall was granted a pension from a Massachusetts court. Some historians consider it the first example of slavery reparations in US history.

A Civil War-era Army order confiscated a huge swathe of land in South Carolina and Georgia from white owners to distribute to freed slaves. The size of the parcels led to the slogan "40 acres and a mule" - a byword for promised slavery reparations - but the promise was ultimately not fulfilled.

Since the Civil War, no large-scale reparations were ever attempted, and until very recently, the idea of paying descendants of slaves was a political non-starter. Black US congressional leaders have introduced a bill every year to establish a committee to study reparations since the 1980s, but it has never come close to becoming law.

"It's a heavy lift," said Robin Rue Simmons, the reparations activist and former Evanston council member who was instrumental in getting the city's reparations law passed.

Ms Simmons sees the Evanston project as one small local step, but one that might have huge implications.

"We have proven that reparations are possible and attainable," she said.

Housing, not slavery

According to Ms Simmons, Evanston's plan was shaped by a series of town hall meetings and consultations with local residents.

But it is notable for what it is not - there are no cash payments and it has no direct link to slavery.

Instead, the project is focused on a specific subset of the black community. To be eligible, adult residents had to have lived in Evanston before 1969, when housing discrimination in various forms was at its height. The system prevented most African-American families from building up generational wealth.

Evanston's reparations take the form of grants of $25,000 which can only be used for house repairs, to pay down a mortgage, or as a down payment on a house.

Those stipulations mean the pool of eligible residents is small - just over 120 applied in the first round.

They are old - in their 70s at least. Several applicants have already died. And the process has taken time. The law passed in 2019, but it was only recently that the first 16 residents were randomly chosen to receive the first pay-outs.

Those factors made residents like Louis Weathers, 87, doubtful that they would ever benefit.

"Like everyone else, I was just waiting for my 40 acres and a mule, which I knew I would never get," he said.

But as it turned out, Mr Weathers was one of the first 16 chosen. He grew up in Evanston after his father moved from Alabama in the 1930s.

Looking for a home

After Army service in Korea, Mr Weathers came back to Evanston and got a job at the Post Office. He and his wife hoped to raise a family, so he purchased a house in Evanston's primarily black Fifth Ward - one of the few neighbourhoods where he could buy.

The location didn't bother him, but the terms of the loan alarmed Mr Weathers. Rather than being given a mortgage, he was given a contract loan - a type of financial instrument then commonly offered to African Americans.

Louis Weathers plans to put the reparations money towards his son's housing costs

Unlike a mortgage, the buyer doesn't legally own the home until the contract loan is paid in full, and doesn't build up equity with payments. Missing just one payment can put the house at risk of foreclosure, with the householder losing everything they invested.

He now lives in an apartment, and plans to put the reparation he received towards his son's mortgage - one of the allowable uses for the money.

After some initial scepticism about the focus on housing costs, he now backs the scheme.

"It serves a good purpose," he said. "If they just handed out cash, to me that's just throwing away money. People wouldn't use it the right way."

Reparations for all?

Not everyone agrees. Cicely Fleming, another black Evanston council member, was the sole dissenting vote against the project, which she called "a housing plan dressed up as reparations".

"This isn't change that can be a beacon for the nation," she said. "It is a dim, weak light."

Ms Fleming and some other activists believe the plan isn't ambitious enough, and that its ties to homeownership leaves out poorer residents - those who can't afford to buy their own homes.

It's a minority view, but even some recipients of the money agree.

Ramona Burton, 73, is thrilled with her new fence, windows and refurbished chimney and electrics. She is "so very grateful" and says she would never have been able to afford the repairs if her number wasn't one of the first chosen.

But, "some people don't have a home. Maybe they have student loans or a car," she said. "I didn't like the restrictions."

Ramona Burton gazes at her repaired chimney and new windows - work made possible by the first reparations program of its kind

A long way to go

Ms Simmons chalked opposition up to "counterproductive" local politics.

"We were informed by members of the black community who participated in the process," she said. "It's practical, political, and it's justice."

When it comes to reparations, "we're not really thinking, 'Should it be a federal policy or a local policy?', 'Should it be housing or education or cash?' It really should be all of it," she added.

She understands that projects like Evanston's are simply impossible in many places.

"We have a history of progressive values. We have a strong, diverse city council as well as a historic black community that is well organised and engaged," she said. "Other communities don't have that.

"We are doing complex work, knowing that we have a long way to go."

3 years ago

76

3 years ago

76

English (US) ·

English (US) ·