ARTICLE AD BOX

By Oksana Antonenko

BBC Russian in Latvia

For Maj Deryugin, there is no conflict between his Russian identity and duty to his Latvian homeland

"I grew up speaking Russian, I am Russian by blood, but I don't associate myself with Russia or the Russian world," says Anatoly Deryugin, a major in the Latvian army.

Anatoly, 43, is one of more than one in three Latvians who speak Russian as their first language. They are now under pressure to prove their loyalty because of Russia's war in Ukraine.

Born and raised in Latvia, he has spent more than half his life in his country's military. His mother is also a Russian-speaker from Latvia, and his father is from eastern Ukraine.

If Maj Deryugin had to defend his country he would fight for Latvia, even if there were Russians like him on the other side of the front line: "If a robber or a murderer comes to your house, no matter what ethnicity he is, Russian-speaking or not, you don't care where he comes from. He is no longer a brother or a friend."

But most Russian speakers in Latvia have spent their lives absorbing Russian state TV, because of a lack of Russian-language content in their own country. And that has left many seeing the world through a narrative that portrays the idea of a united Russian world with the Kremlin at its centre.

Support for Ukraine amongst Latvia's Russian speakers has grown since Vladimir Putin's invasion in February

Until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Russian and Ukrainian families were sent to Latvia as part of a programme of forced relocation of labour. Others are descendants of Russians who moved to Latvia centuries ago, and some originate from Belarus or are of Jewish descent.

Latvian and international leaders are wary of Vladimir Putin's designs on the Baltic republics.

His justification for invading Ukraine was that the eastern Donbas region was home to Russian-speakers who needed the Kremlin's protection. Latvia fears he could apply the same logic there.

Nato has responded by doubling the size of its force in Latvia, with more to come, and the government in Riga is even discussing conscription.

Russian media channels have been banned, and any public support for the war in Ukraine or Russian aggression can now lead to criminal prosecution.

Monuments seen as glorifying the old Soviet Union are to be removed. High on the list is the towering Victory monument in a Riga park.

Latvians are not allowed to hold dual Russian citizenship. And now life is becoming harder for Russian nationals who live in Latvia, after President Egils Levits said those who support Russia's war should lose their residence permit.

"Patriotism and the attitude to defending one's country are not related to the language you speak," argues Maj Deryugin.

He commands the 34th Infantry battalion of Latvia's "Zemessardze" voluntary national guard, based near the eastern city of Daugavpils, 30km (18 miles) from the Belarusian border.

The war in Ukraine has prompted a spike in volunteers signing up for the Latvian National Guard

In this region, 90% of the population have Russian as their mother tongue, as do many of his recruits.

For Latvia's authorities the loyalty of its citizens is at least as important as the tanks and soldiers it can muster. The question being discussed behind closed doors is who do Latvian Russians really believe: Latvian, Western and Ukrainian leaders - or Russian propaganda, which was allowed on Latvia's airwaves for 30 years.

Since the beginning of the war in Ukraine, polling company SKDS has been monitoring the mood of local Russian speakers. In March, 22% supported Ukraine after Russia's invasion, but by June that had jumped to 40%.

The ban on Russian state media clearly made a difference, but there is more to the change in attitudes.

Until 2017, Latvia's social democratic Harmony party, which represents the interests of the Russian minority, was widely seen as pro-Russian and had ties with the ruling United Russia party in Moscow.

But Harmony has condemned Russia's invasion of Ukraine, and one of its MPs, Boris Cilevics, describes becoming totally disillusioned with the Kremlin's expansionist ideology: "[Modern Russia] is absolutely analogous of the policy of Nazi Germany - the only chance for normalisation is a military defeat for Russia."

His parents are both professors of Russian language, so Russian literature and culture are important to his whole family. But since the invasion of Ukraine he says he finds it hard to love his Russian heritage.

"The aggression in Ukraine completely discredited all this and made everything related to the word Russian toxic," he says.

"But for many Russian-speaking people in Latvia, Russian identity is very important. For many of them admitting that Russia is the aggressor… is very difficult, it is such a psychological breakdown."

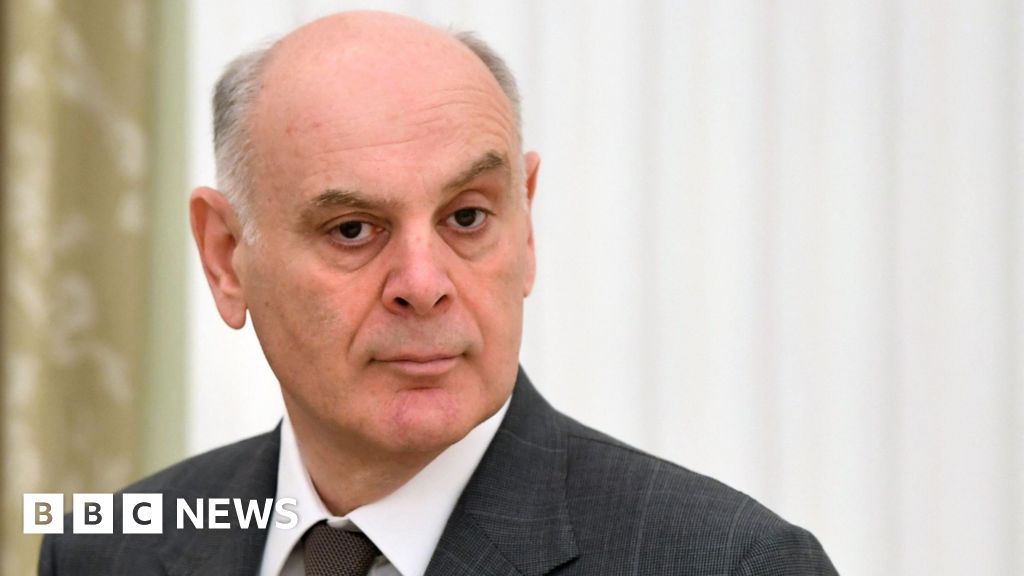

Alexander Dubyako could face five years in jail for displaying the Russian flag

Alexander, 19, was arrested after waving a Russian flag and giving a speech in front of Riga's huge Soviet war memorial on 10 May.

He was attending an unofficial gathering to celebrate Victory Day, an annual holiday that commemorates the Soviet victory over Nazi Germany.

Official celebrations were banned as they were seen as a glorification of Russia, which led to protests like the one Alex attended.

"I saw the flag as a symbol of unity, I consider the Victory Day a day of unity. There was just an incredible atmosphere, a sense of togetherness that I have not seen in Latvia for a long time," he told the BBC.

Latvian police saw his action as a sign of support for Russian aggression in Ukraine, which Alexander and his family say was not the case.

He was charged under a law that outlaws glorification of genocide and war crimes and he is now awaiting sentencing. The maximum punishment is five years in prison.

"My grandfather went through the war… we believe this is a memory that should be honoured and respected," says his mother Svetlana who was with him when he was arrested. Both have since received death threats on social media.

"We are forced to be ashamed, to be afraid that we are Russians, but this is also wrong."

For the majority of Latvia's Russian-speakers, Victory Day has always been important, even though many condemn Russian aggression and consider themselves Latvian patriots.

But the more they feel they are being asked to give up their identity for the sake of loyalty to the West, the more divided Latvian society could become.

Latvia's government, meanwhile, believes it has to prepare for potential military aggression from its bigger neighbour.

"Together we are strong": A mural in Riga shows two women in Ukrainian and Latvian colours

2 years ago

29

2 years ago

29

English (US)

English (US)