ARTICLE AD BOX

Image source, Pacemaker

Image source, Pacemaker

By Ciaran McCauley

BBC News NI

On this day 10 years ago, one of Ireland and the world's most famous poets, Seamus Heaney, died at the age of 74. But how is he viewed in 2023? We asked six people - from teenage writers to teachers to poets from Northern Ireland and beyond - to dig into the Nobel Prize winner's legacy.

Kaila Patterson and Leonie Hanan were five and six years old respectively when Seamus Heaney died. Old enough to know he was someone, not old enough to know who.

Now 15 and 16, they could easily be forgiven for still not knowing much about him.

But they're writers who want to create art, and in this part of the world Seamus Heaney is still the benchmark for what can come from that dream.

That doesn't mean they can't be uncritical. While Kaila says Heaney's success in "addressing Irish themes in a universal way" gives her confidence to follow his example, Leonie admits she thought he was overrated and over-analysed when she first came across him in school.

"I was wrong," she adds now, with a laugh.

Image source, Kaila Patterson / Leonie Hanan

Image caption,Kaila Patterson (left) and Leonie Hanan are young writers

Her conversion came via one of Heaney's most famous poems, Digging, which she picked up outside the classroom.

"I liked that it was about his writing… when we studied it in class, I needed help to understand it," she says.

"But the more I read his work, the more I saw you can understand it in your own way."

When you speak to Leonie about Digging, or Kaila about one of her favourites, Mid-Term Break, and how her heart dropped with its final shattering line, you understand when they talk about the influence of Seamus Heaney, they mean it.

A practical legacy

Both girls are members of Fighting Words NI, a creative writing charity which started out in 2015, two years after Heaney's death.

It's part of what director Hilary Copeland describes as a "big eco-system", where writers across Northern Ireland can get practical support.

The infrastructure that exists for writers - such as the Seamus Heaney Centre at Queen's University Belfast, which is getting a new £4.9m venue; the HomePlace in Bellaghy; and various organisations and groups - she says has come "off the back of Heaney - and we don't take that for granted".

Image source, Fighting Words NI

Image caption,'It's a big eco-system here - and we don't take that for granted' says Hilary Copeland

It's an infrastructure that works.

There's something else important about his legacy too, she says - this eco-system has grown around "a proliferation of writers, not just men, but women, queer people and those outside of Northern Ireland who now call it home".

Heaney, she says, opened that door.

If that is so, South African-born poet Nandi Joli walked through.

Image source, Nandi Jola

Image caption,"There's also power in writing things" - South African-born poet and writer Nandi Jola

She moved to Northern Ireland in 2001 - it was just her luck, she laughs, that the Nobel winner would make his only visit to her home country a year later.

During that visit he read Digging, which centres on rural Ireland - and yet that "squat pen rests; snug as a gun" called directly to Nandi's own experience.

"He's saying, someone could have chosen to follow the ANC (African National Congress), the struggle in South Africa, but squat pen - there's also power in writing things," she says.

"We can't all be [Nelson] Mandela, we can't all go to prison but we can choose how we use our words."

On Sunday, Nandi was one of 10 poets taking part in a commemoration event at the Seamus Heaney HomePlace.

She came to him first properly when studying at Queen's and found remarkable parallels in his poetry and her own life.

Image source, Nandi Jola

Image caption,Nandi with the poets who took part in a commemoration event for Seamus Heaney last weekend

One of her favourite Heaney poems is England's Difficulty, in which he wrote about how he "moved like a double agent".

It reminded Nandi of how when she was nine, living under apartheid, she had no access to library books.

So a neighbour librarian working "on the white side of town" began to bring her books in secret - it was a covert arrangement that lasted about 15 years.

"This was something that empowered me, was important - but detrimental to me as well if anyone found out," she remembers.

Decades later she found herself in Northern Ireland, a part of that artistic community Hilary Copeland described, surrounded by mentors helping her - and, once again, being given books.

"They give me prized books from their collections and made me promise to look after them. Life has come full circle," she says.

Elevating the ordinariness

For Clare McWilliams, from Bangor, County Down, Heaney's most telling influence is that he gave her the freedom to write about what she knew best - everyday life.

It's a lesson that has been particularly important in her work as a performance poet.

"Everyone in Northern Ireland, as soon as you talk about poetry, they think about the political - but Heaney wrote about the mundane and secular rather than the sacred," she says.

"He had a way of bringing ordinariness to life. As someone from a working-class background, I could identify with that.

"He engaged in things people knew and used colloquialisms, writing how people talk."

Image source, Clare McWilliams

Image caption,"We're so lucky we have recordings of him reading his poetry aloud" - performance poet Clare McWilliams

Growing up, she says, Heaney was one of the few voices like hers on television.

In the way he captured the landscape and people in his poetry, she feels he brought a more positive image of Northern Ireland when it was most needed.

It may be why, she says, both Protestant and Catholic communities embraced him.

As for performance poetry - or spoken word - that is a world generally removed from the more traditional verse of Heaney.

But even here, his influence looms, as we "can hear the rhythm in Heaney's work".

"It's important to be able to hear poetry read aloud and we're so lucky we have recordings and can hear read his work in his voice," she says.

Heaney in the classroom

Apart from her writing, Clare also works as a facilitator, running workshops and events often for younger people and newcomers to poetry.

Sometimes Heaney can be a challenge for new audiences, she says, hinting at something also mentioned by Leonie and Hilary - the classic issue of people being turned off when reading turns into schoolwork.

Brian McGilloway is best known for his series of crime fiction bestsellers.

But before all that he was a pupil and then an English teacher at St Columb's College in Londonderry, where Heaney was a student, responsible for connecting young people to the Nobel Prize winner's works.

Image source, Brian McGilloway

Image caption,Brian McGilloway is best known as a crime author, but he was also an English teacher at Heaney's old school

He remembers studying Mid-Term Break in "the College" and how "the bell you heard every day was the same bell Heaney was writing about".

"This was well before the Nobel but there was an enormous sense of pride. It was a privilege," he says.

For him, teaching kids to connect with poetry like Heaney's is a joy: "You think you know these poems really well, but kids will see something you haven't noticed."

Still, he freely admits he was taught Mid-Term Break about half a dozen times at school.

"They can become overly familiar. I remember Heaney and [fellow Nobel Prize winner, John] Hume visiting the school and I think the kids were so used to seeing them they didn't grasp the significance," he says.

Even he became jaded from learning Heaney at school, before rediscovering the work afresh after he left school.

'You read it and go - yes!'

It's also possible, he says, that some poems have meant more to him at different times of his life. He thinks about what his favourite Heaney poem might be now, and mentions A Call, which gently details Heaney phoning home to speak to his parents.

"The poem felt like someone had glimpsed into my soul," he says.

"Then there's something like Human Chain as well, about having a shared connection and shared expression.

"It speaks to you, you read it and just go: 'Yes!'"

And as a writer, even of crime fiction, Heaney has been an inevitable influence.

"St Columb's is the school of Heaney and [Brian] Friel and [Seamus] Deane, so that is both inspiring but also intimidating. It means someone here can follow that path, and there's also there's this shadow… but it's inspiring to see that level of success not just in literature but in life."

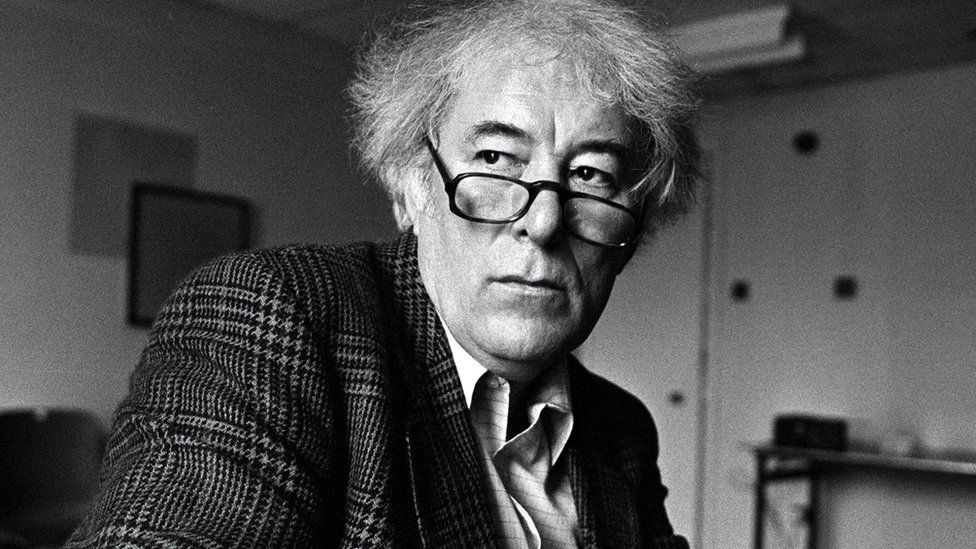

Image source, Pacemaker

Image caption,A legacy that continues "to set the darkness echoing" - Seamus Heaney, pictued in 1990

It's inspiration then - perhaps aside from the practical resources and artistic community that has emerged and thrived in his wake - that may remain Heaney's greatest legacy.

When asked about her favourite Heaney line, Leonie Hanan talks about Personal Helicon's final lines: "I rhyme/to see myself, to set the darkness echoing."

That's Leonie's inspiration, to have the freedom to write in that way about her own life - to set her own darkness echoing.

Kaila, meanwhile, returns once again to that squat pen in Digging.

"That image with the pen is a reminder for everyone that writing is powerful," she says.

"It can be tough but it can bring incredible results. That art of digging can help us create our own path to a brighter future."

For more on the Nobel Prize winner, you can listen to The Four Sides of Seamus Heaney on BBC Sounds now.

1 year ago

30

1 year ago

30

English (US) ·

English (US) ·