ARTICLE AD BOX

Sir Frank Williams teams won seven Formula 1 drivers' titles

Sir Frank Williams teams won seven Formula 1 drivers' titlesSir Frank Williams, who has died aged 79, was one of the greatest Formula 1 team owners in history and a man who became an icon through his determination to compete at the highest level despite a severe disability.

Sir Frank, who first ran a team in F1 in 1969 and set up Williams Grand Prix Engineering in 1977 before launching into more than two decades of success, was a quadriplegic after breaking his neck in a car crash in March 1986.

Once he had come through months of recovery and rehabilitation, he launched himself back into F1, a sport he loved with a passion matched by very few, and went on to his greatest achievements.

His team won seven drivers' titles and nine constructors' titles, but in recent years had fallen to the back of the grid, and after racking up £13m losses in 2019 it was sold to an investment group in August 2020 and the family stepped aside.

Williams did not so much love F1 as was consumed by it. Although his health prevented his active involvement in the team for the last few years, he literally lived in the factory. The team he set up was his life - as it always had been.

Williams' first venture as a team owner was in 1969

Williams' first venture as a team owner was in 1969A measure of his devotion to the sport was that he was prepared to put his own comfort second to the success of his team. When he faced a decision some years ago between building a wind tunnel that would help make the cars go faster and keeping the private plane that allowed him to attend the farthest-flung races, he chose the wind tunnel.

To those who had studied his career closely, this sort of decision was no surprise, for Williams had to endure a number of difficult and painful years of financial struggle before finally establishing himself in the sport.

From his first venture as a team owner in 1969, Williams went through several guises, all of them awfully uncompetitive and terribly financially insecure.

At one stage, so tight had money become, he was famously operating his business out of a phone booth, after losing the premises he was using.

The breakthrough came in 1977, when he teamed up with the brilliant engineer Patrick Head and became a trend-setter in finding money from the Middle East.

Helped by increased resources allowed by Saudi money, Head's first car for the team, FW06, established them as serious contenders for the first time in 1978. And from the mid-point of 1979, with the new FW07 - one of history's great F1 cars - Williams became the sport's absolute pace-setters.

Poor reliability and an eccentric scoring system cost them the world championship in 1979, but they made no mistake in 1980, with Australian Alan Jones romping to the title.

Jones and his Argentine team-mate Carlos Reutemann both narrowly missed out on a Williams double in 1981 before both quit the sport. But the Finn Keke Rosberg took another title in 1982, albeit one based on consistency after the Ferrari team lost both its lead drivers, one killed and one seriously injured, in remarkably similar accidents, and the faster Renaults were let down by reliability.

As F1's first turbo era took hold, a new partnership with Honda started slowly in 1984, with just one win, but gathered pace through 1985 until in 1986 Williams again emerged with a dominant car, the FW11.

But before the season even started, Williams's very future was cast into doubt by its founder's injury.

Racing his driver Nelson Piquet to the airport in hire cars after a pre-season test in the south of France, Williams turned his car over, and the impact broke his neck. Williams's team manager Peter Windsor, now a journalist, was in the car with him and was unhurt.

"The car banged over a few times and I'm ashamed to say it was either the sixth or seventh rollover accident I'd had in my life," Williams said.

"I remember the sharp pain in my neck. I thought: 'Wow, rolling over isn't supposed to hurt that much.' The car finished upside down and I tried to reach for the safety belt to get myself out and I couldn't do it.

"I knew I was going to have the big one but I couldn't slow myself down."

When Williams suffered his injury, he was 43. Doctors pointed out to those close to him that, based on the examples of other people with similar problems, he would be lucky to live another 10 years. It says a lot about his determination and single-mindedness that he managed more than three times that.

Williams had been a very active man and a keen runner, but he was determined to carry on despite the difficulties caused by the accident.

Sir Frank's wife Ginny (second right) died in 2013 of cancer. Daughter Claire (left) stepped away from the team in 2020

Sir Frank's wife Ginny (second right) died in 2013 of cancer. Daughter Claire (left) stepped away from the team in 2020"The thought of retiring or selling the team never crossed my mind," he said, "and I also suppose recognised subconsciously it would be a great daily antidote for the difficulties I would find myself in. It's a fantastic job, a very exciting business, highly competitive, always something to worry about. Which can be quite healthy, actually."

There followed months of recovery, through which Head kept the team going, and public-school educated Williams never betrayed any sense of self-pity, depression or any of the other emotions that might be expected of someone in his situation.

His late wife Ginny, who died of cancer in 2013, wrote a book about their marriage.

In it, she describes how, in the months after the accident, he talked about it very little, and simply said that they had had several good years of one kind of life together and now they just had to get used to a different one. That remark gave her a superbly apt title for the book, A Different Kind of Life.

Head said: "I'm sure Frank had some terrible moments thinking about the change in his life but he was never one to sit around and be sorry for himself.

"Frank was always very pragmatic about 'what is the problem and how can I deal with it?' and applied that to himself and his injury.

"His enthusiasm and positive attitude always overcome any difficulties he has."

The first few months after his accident Williams spent focusing on getting into a condition that would allow him to get back to attending races.

Head has described how Williams ran his life with "military precision", adding: "Once he'd found out what the things were that would cause him problems, he adapted his lifestyle to give himself the best opportunities. He's very disciplined about that sort of thing - it's remarkable what he has done since then.

"Frank's always been quite private in his own emotions and in control of his interactions with other people. Once we'd got used to the fact that he wasn't the same person he was before, that he was in a wheelchair, things just sort of carried on as normal."

Williams' attitude to his disability was simple - it was his own fault he ended up that way so he had better just get on with it.

He would say in his clipped manner: "I've had a wonderful life - wouldn't dream of changing anything, truthfully."

In 1986, Williams lost the title to McLaren's Alain Prost, despite the superiority of their car, because drivers Piquet and Nigel Mansell split the points between them.

But in 1987, with Williams now back at work full time, they dominated, Piquet's consistency trumping Mansell's greater speed and poorer reliability.

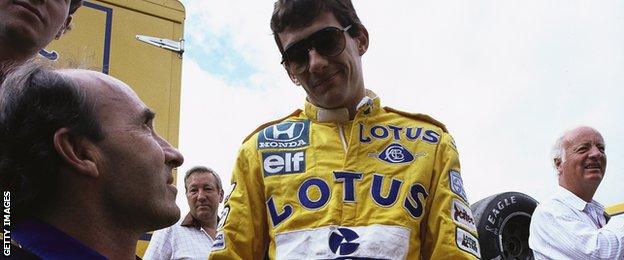

Ayrton Senna drove for Toleman, Lotus and McLaren before joining Williams in 1994

Ayrton Senna drove for Toleman, Lotus and McLaren before joining Williams in 1994At the end of that year, Williams lost their Honda engines, the dominant force in F1, and many feared for the future of a team without a factory engine supply and with a man in a wheelchair at the helm.

In fact, Williams were about to embark on their period of greatest success.

Williams replaced Honda with Renault, forging a partnership that set new standards for F1, dominating the 1992 and 1993 seasons with cars bristling with technology such as active suspension, allowing first Mansell and then new signing Alain Prost to crush the opposition.

This success illustrated another aspect of Williams's achievements. The titles they won with famous drivers such as Jones, Rosberg, Piquet, Mansell, Prost and Damon Hill came thanks to the team's investment in world-class engineering.

Williams have provided the platform for some of the sport's most brilliant engineers to make their names.

Among them was Adrian Newey, who was Williams' chief designer from 1991-1996, joined McLaren until 2005 and then masterminded the rise of Red Bull to four consecutive world titles from 2010-14.

And Ross Brawn, who started his F1 career at Williams and went on to win two world titles with Benetton before moving to Ferrari and running their technical department in their dominant period with Michael Schumacher, and is now managing director of F1.

Among Williams' greatest regrets, though, was that his time working with Ayrton Senna was so short.

Williams was the first team to give the great Brazilian a trial in F1, back in the summer 1983, but decided against signing him. They finally joined forces 10 years later, only for Senna to be killed in a crash at the 1994 San Marino Grand Prix just three races into his Williams career.

"I felt that we had been given a great responsibility providing him with a car, and we let him down," said Williams.

Senna's death led to a lengthy legal process in Italy in which Williams, Head and Newey all faced manslaughter charges, but were ultimately acquitted.

The Renault partnership came to an end in 1997, after consecutive titles for Hill and Jacques Villeneuve, and there was another brief hiatus with customer engines before a new partnership with BMW started in 2000.

There were great hopes for an alliance of such powerhouses, but the relationship fell short and in 2005 BMW, disappointed with Williams's performance, pulled out and set up its own team.

It was the death knell for Williams as a front-running team. There was an eight-year gap between Juan Pablo Montoya's victory in a Williams-BMW in the 2004 Brazilian Grand Prix and the shock win for Pastor Maldonado in Spain in 2012, which was the last time a Williams took the chequered flag.

Since then, there was a brief upturn in form in 2014 and 2015, when the strength of Mercedes engines at the start of F1's hybrid engine era gave Williams a leg up, but then a slow decline, and the team have finished last in the championship for the past three years.

The new owners, Dorilton Capital, led by offshore banker Peter de Putron, have bought into the value of the family name and intend to keep it on.

It underlines the value and significance of the achievements of a man who stamped his character on a team that seems to epitomise the racing spirit required for success in the highest form of motorsport.

Williams is survived by his three children, Jonathan, Jamie and Claire.

3 years ago

198

3 years ago

198

English (US) ·

English (US) ·