ARTICLE AD BOX

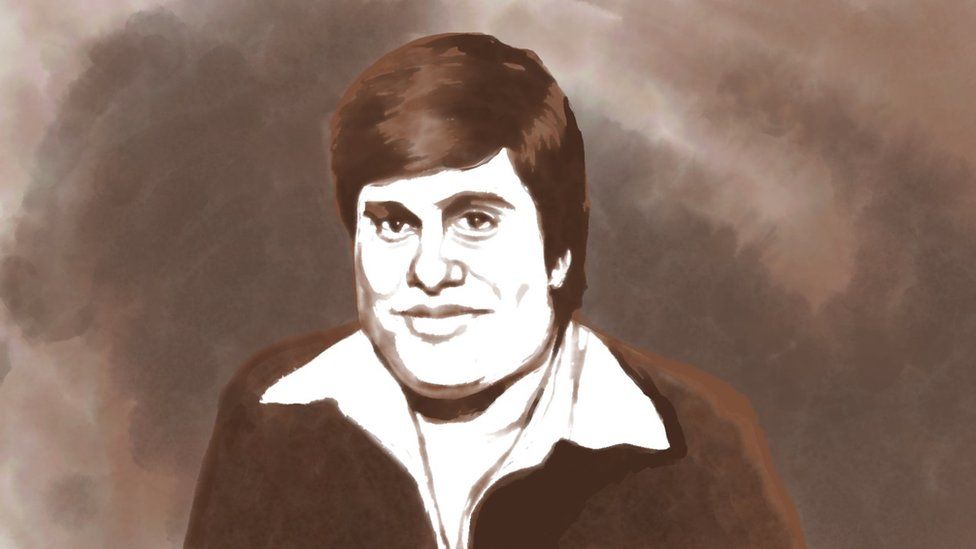

Image source, Gopal Shoonya/BBC

Image source, Gopal Shoonya/BBC

Steve Banerjee, whose real name was Somen Banerjee, founded the male strip club Chippendales in Los Angeles in 1979

By Meryl Sebastian

BBC News, Kochi

Muscled men wearing bow-ties and G-strings to entertain women in smoky clubs is not a legacy one usually associates with an Indian-American immigrant.

But Mumbai-born Steve Banerjee turned the conventional American Dream for a South Asian on its head when he founded the male strip club Chippendales in Los Angeles in 1979.

The rest is history: Banerjee made a fortune from what turned out to be a hugely successful franchise. Add sex, drugs and murder to the mix and Banerjee's story becomes the stuff of sensational legend.

In India, Banerjee - and his work - is hardly known. In the US, the Chippendales brand appears to have eclipsed the reputation of its controversial founder. That is now changing.

Nearly three decades after his death, a podcast and a host of TV shows - including Hulu's latest drama series Welcome To Chippendales, starring Kumail Nanjiani - are revisiting Banerjee's story.

"Most people would think that the founder of Chippendales was an outgoing party animal who chased women, did drugs, and drank heavily," says Scott MacDonald, co-author of the 2014 book Deadly Dance: The Chippendales Murders. "Steve was a reserved, controlled man with a clear goal of creating a worldwide brand to rival Disney, Playboy or Polo."

Image source, Hulu

Image caption,Kumail Nanjiani plays Banerjee in Hulu's drama series

He is "a unique part of the story", says historian Natalia Mehlman Petrzela, whose podcast, Welcome to Your Fantasy, renewed interest in the Chippendales legacy. Bespectacled, brown and stocky, Banerjee stood in contrast to the "white, blonde, California man" fantasy sold by his franchise.

Banerjee, who hailed from a family of printers, left India for Canada as a 20-something man in the late 1960s. He soon ended up in California, where he owned a gas station in Los Angeles.

Banerjee, however, had bigger ambitions. "I want to be driving that car," he would say when people drove up to fill up their fancy vehicles, Petrzela says.

In the 1970s, Banerjee used his savings to buy a dive bar in LA which he called Destiny II, and tried everything to draw in crowds - backgammon games, magic shows and mud wrestling among women.

In 1979, Paul Snider, a nightclub promoter, suggested that Banerjee bring in male strippers - usually only seen in gay clubs - for a show aimed at women.

By now, the bar had been renamed Chippendales to suggest a classier experience.

The strip shows were advertised all across West LA - everywhere women gathered, from nail salons to women's restrooms, Petrzela says on her podcast.

An instant hit, Chippendales soon drew large crowds of women every night.

Image source, Getty Images

Image caption,Until Chippendales, male stripping had typically been seen at gay bars

Inspired by Hugh Hefner's Playboy bunnies, the dancers wore cuffs and collars with tight black pants.

For 1980s America "this was shocking", Petrzela says. But in the wake of the sexual revolution of the 1970s, Banerjee's Chippendales also came at a time when women's empowerment and sexual liberation could be commodified, the historian explains.

Women needed a place "they could have a blast and be exonerated", Barbara Ligeti, a club promoter, says in the A&E docu-series Secrets of the Chippendales Murders. "They could see each other, have a few drinks, pinch a butt, put $20 in a G-string of a good-looking guy."

Banerjee wanted to create a "Disneyland for adults", a brand big enough to rival those of his heroes - Hefner and Walt Disney.

In the early 80s, he met Nick De Noia, an Emmy Award-winning director and choreographer, who convinced him that the show needed an upgrade. Chippendales dancers and producers credit De Noia with turning the show into an interactive, theatrical production using characters and storylines.

Image source, Getty Images

Image caption,Nick De Noia, right, transformed the performance routine of the Chippendales dancers

De Noia helped take Chippendales to New York City and expand the production across America through a successful tour.

But things soon came to a head between the two men as the charismatic choreographer became the face of the brand - dubbed "Mr Chippendale" in the media - while Banerjee remained in the background, running the operation from LA.

As tensions rose, De Noia and Banerjee dissolved their partnership and the choreographer planned to start his own company - US Male.

In the docu-series, a former associate producer at Chippendales who helped De Noia with his new venture says it sent Banerjee "over the edge".

Many who knew Banerjee described him as a "paranoid" man for whom success was a zero-sum game. "He felt if others succeeded, that would necessarily take away from his own success," Petrzela says.

As rival strip clubs popped up, Banerjee hired Ray Colon, a friend-turned-hitman, to sabotage competitors.

In 1987, under Banerjee's orders, Colon recruited an accomplice who shot De Noia dead in his office.

While friends and collaborators suspected Banerjee's hand in the crime, it was years before FBI investigators made the link.

Banerjee's lawyer Bruce Nahin said "the murder didn't affect the brand at all".

Image source, Getty Images

Image caption,Chippendales' success had women lining up for shows outside its clubs

Chippendales grew, travelling to Australia and Europe.

In 1991, while in the UK with the Chippendales tour, Banerjee asked Colon to take out members of a rival troupe started by former dancers from his club.

According to FBI evidence, the plan was to inject them with cyanide which Colon provided to an accomplice named Strawberry.

But an apprehensive Strawberry reported Colon to the FBI.

Colon was arrested and charged with conspiracy and murder for hire. According to the agency, 46 grams of cyanide were found during a raid on Colon's house.

For months after his arrest, Colon remained loyal to Banerjee, pleading not guilty. "It was only after Steve refused to help him by paying for an attorney that Ray finally broke with Steve," MacDonald says.

In 1993, the FBI finally gathered enough evidence against Banerjee by using Colon to secretly record their conversation. Banerjee was arrested for racketeering, conspiracy and murder for hire among other charges. He pleaded not guilty.

Image source, Getty Images

Image caption,The Chippendales touring troupe took its act across North America and Europe

After the trial went on for a few months, Banerjee agreed to a plea deal - 26 years in prison and forfeiture of Chippendales ownership to the US government.

Petrzela says Banerjee's lawyers tried hard to avoid the seizure of the enterprise, but to no avail. In October 1994, a day before he was to be sentenced, Banerjee killed himself in his jail cell.

"Very few Indian Americans know his story," says Anirvan Chatterjee, who organises a South Asian radical history walking tour in Berkeley. Banerjee's life was "the funhouse mirror version of the standard 1990s Indian California business story", he says, and it contradicted every stereotype about the community.

In her research, Petrzela found Banerjee had tried hard to assimilate and become a true-blue California businessman, yet in the memory of her interviewees his Indian accent stood out. "It's clear other people always saw him as very foreign and very Indian," she says. "Even in death, the first thing that people did when commenting on him is start imitating his accent."

1 year ago

56

1 year ago

56

English (US)

English (US)