ARTICLE AD BOX

By Secunder Kermani

BBC News, Kabul

Crowds gather outside the cancer ward in Kabul

Five-year-old Fazlur Rahman has a stage four tumour in his neck and Afghan doctors are battling to prolong his young life with chemotherapy.

He lies in an overcrowded and under-resourced cancer ward in Kabul's Jamhuriat hospital, one of just three cancer centres still functioning in the country.

At the hospital you can see the impact aid is having, but also why more is needed.

The treatment is free, as the International Committee of the Red Cross has stepped in to fund essential hospital services, but patients now have to buy at least some of the medicines themselves.

The Afghan economy has been left shattered by the aftershocks of the Taliban takeover, and even raising around $100 is a major challenge for the child's father, Abdul Bari, a farmer from the remote west of the country.

"I've been borrowing money from everyone I know just to try and get enough to pay for my travel here, a place to stay and for the medicine," he tells us.

Previously in Afghanistan, around 75% of public spending was derived from foreign grants.

Those grants have stopped since the Taliban came to power, though humanitarian aid has continued, and around $9bn (£7bn) of Afghanistan's foreign reserves have been frozen, leading to a shortage of both funds and physical cash in the country.

A report from the World Bank last week warned that more than a third of the population was now no longer able to meet basic food needs.

Mazaria, a labourer from rural Afghanistan says she can no longer afford medicine once provided for free

Patients on the cancer ward like 50-year-old Mazaria from northern Takhar province are selling everything they own, just to be able to buy medicines that in the past would've been provided for free.

"What could we do?" Mazaria asks. "We're labourers… we had a cow and a donkey, so we sold them. We don't have anything left.

"We've borrowed money from my brothers and my husbands' relatives as well as our neighbours."

Dr Manucher is in charge of the cancer ward. At times, he says, hospital staff club together to pay for the medicines on behalf of the poorest patients.

"Unfortunately we don't have a sufficient budget," he tells us.

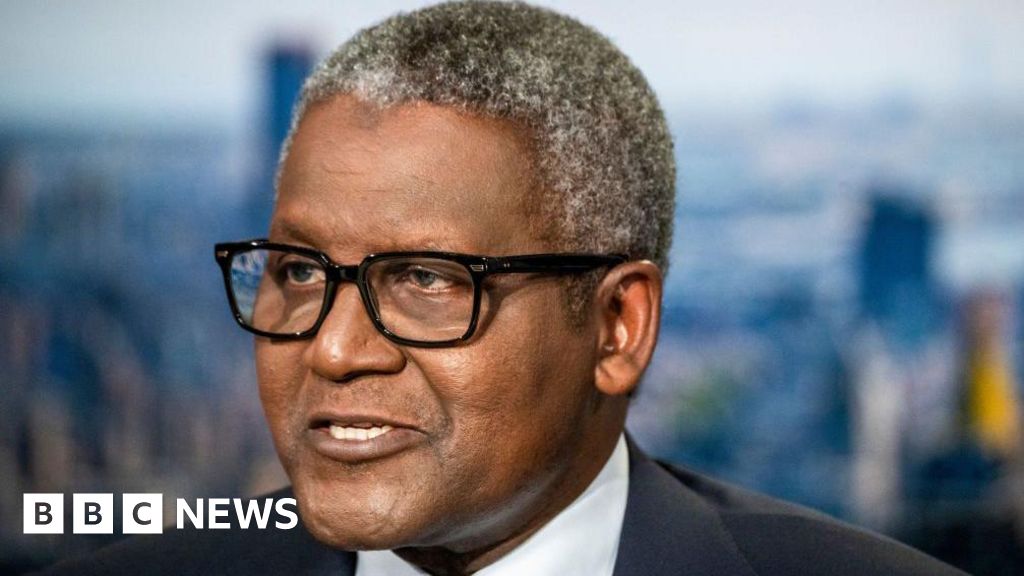

Doctor Manucher says his budget has collapsed since the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan

In fact, his budget is zero. The department is only still running because the ICRC is paying salaries and for some medicines.

By contrast, last year, he received a budget of $1m from the Ministry of Public Health.

The UN is calling for more than $4bn to address the humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan.

A major international conference last month called for $4.4bn to address the humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan - a little over $2.4bn was pledged.

There is a desperate need to help save lives, with a rise in severely malnourished children and struggling families resorting to marrying off daughters at even younger ages than usual.

But aid workers and diplomats all recognise the importance of going beyond those immediate needs and helping Afghanistan build a more sustainable future.

However, resuming development funding, and unfreezing Afghanistan's reserves, are issues the international community is still grappling with, especially as the Taliban grow increasingly hardline.

Last week the Taliban announced girls schools across the country will be closed

Fears have been expressed that anger at the group's decision not to allow teenage girls back to school in most of the country will lead to donors becoming hesitant about providing much needed funding.

In the meantime, it is inevitably the most vulnerable who are suffering the most.

On the eastern edge of Kabul we visit a camp for displaced families.

The fighting they fled has now ended, but they complain they can't afford to move back and rebuild their homes.

Children crowd into a community-run classroom. The nearby government school is free, but 12-year-old Parwana says she can't afford to buy the uniform. It's been around three years since she last went there.

Parwana (right) says her family cannot afford to buy school uniforms for her

"Life is getting worse, my mother washes clothes but she can't earn enough to buy us food and now she's getting ill," she says.

Elsewhere as evening approaches, outside Kabul's many naan shops, it's common to see small groups of women and children sat down on the pavement, hoping customers will buy them a piece of bread or two.

On one street in the north of the city, where a local charity distributes bread every day, close to a hundred people have gathered.

There's an air of desperation as some mistake us for aid workers, trying to wave copies of their IDs in our face, hoping we can add their names to a list for donations.

"If you aren't helping us, why are you here?" says one.

Another cries out as we leave: "Sometimes my children eat, sometimes they don't."

2 years ago

45

2 years ago

45

English (US)

English (US)