ARTICLE AD BOX

Image source, Liverpool Hope University

Image source, Liverpool Hope University

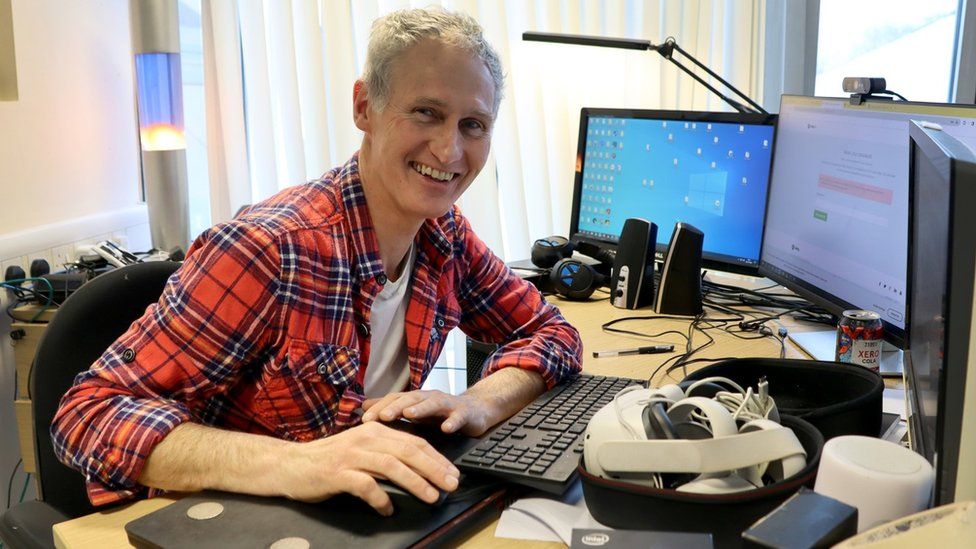

Prof David Reid now talks about football with an AI companion that can speak out loud

Technology reporter Stephanie Power likes to think she is comfortable with artificial intelligence, but the new breed of talking AI companions unnerve her, as she reports.

My husband is a huge Liverpool FC fan who gets into a state of anxiety almost every time they play.

It is very irritating, but I've recently realised that the best technique is to avoid him before, during, and sometimes after a game.

Recently following a match, I could hear a friendly woman's voice talking to him in his home office.

"Oh yes, it was a tough game, but the reds really are on good form," she said. "Liverpool's strikers were able to deliver the goods."

Who was this woman? And why was she indulging David in this way?

Image source, Getty Images

Image caption,Conservational AI companions speak to you via your mobile phone, computer, or connected speakers

It turns out that my husband was trying out an app called Pi.ai. Launched last year by US tech firm Inflection AI, it is an example of a growing trend called conversational AI.

Rather than just answer any questions you give it, or perhaps do your homework for you, the idea is that the AI can become a friend or companion who talks to you - out loud - via your computer or phone's speakers.

And the more you chat with the AI, the more it is said to understand you, and so its replies aim to become more tailored to you, and more like having a natural conversation with a friend. That, at least, is the theory.

With Pi.ai you still have to type in your half of the conversation, but it replies in one of six different human-like voices that you can choose from. These range from a fast-talking American man, to the posh English female voice that my husband was talking to.

If your reaction is "but Amazon's Alexa has been talking out loud to me for years", conversational AI aims to give you a far more natural, flowing chat, both in terms of the words and sentences that the AI chooses, and the way it says them out loud.

"People might say, we've had voice in technology for ages, and they're probably thinking of Alexa," says David Reid, a professor in AI at Liverpool Hope University, and the man who just happens to be my Liverpool-obsessed husband.

"But the global market in conversational AI is expected to grow to $30bn [£24bn] in the next five years. If you want an idea of what this might look like, then imagine Alexa, but with empathy."

Tech firms are now racing to release their own conversational AI companions. Google has Vertex AI Conversation, Microsoft has Azure AI, and there are now a host of start-ups in the sector.

Meanwhile, Amazon is sticking with Alexa, but planning to add conversational AI to it, plus a more human-like voice.

Rohit Prasad, head scientist for Alexa, explained his hopes, using another sporting analogy, in a speech last year. "The [Boston] Red Sox are my favourite [baseball] team," he said. "Imagine if they won, then Alexa would respond in a joyful voice. If they lost, it will be empathetic to me."

To make the human-like voices for conversational AI, it usually starts with a recording of an actual human. However, the technology then needs to be able to adapt this to put across the required tone or volume, to put words together in a natural-sounding way.

"Our tools can take into account the spirit of a sentence, and how the words connect to each other," says Mati Staniszewski, the boss of Eleven Labs, a UK tech firm that has created 40 AI voices across gender, age and accent. "This means we can capture the intonation, tone and emotion the AI speaker intends to convey."

Mr Staniszewski says intonation is "vital".

"Getting that right is what stops an AI from sounding robotic. Emotions and intonation often need to stretch and resonate across a number of sentences to tie a particular train of thought together. And tone and pacing convey intent, so the model takes the surrounding context into account, maintaining the right flow."

Image source, Trevor Cox

Image caption,Prof Cox says that developers of conversational AI likely pick accents that are easy for people to understand

Trevor Cox, a professor of acoustic engineering at the University of Salford, says that the developers of conversational AI will likely avoid strong, regional accents.

"There are still prejudices around strong regional accents," he says. "Studies suggest that the harder a voice is to understand, then the less likely we are to believe what is being said.

"This is beyond accent and more about flow. Our brains want to decode information quickly. So the creators of an AI will want to make sure the brain has access to that fast decoding.

"Then beyond that there is tone. Messages are conveyed by much more than the words, it is how you say them. So if an AI can convey happiness, excitability or boredom then that all helps."

David Harley, a lecturer in Cyberpsychology at Brighton University, says there are risks as computer voices become ever more human-like.

"My concern lies in the fact that people may start to view AI companions and therapists as effective in solving all life's problems," he says. "They may start to tailor their lives around the AI advice, which is blind to these other profound aspects of being human."

He adds that people will have to remind themselves that their AI companion is not a real person.

I had a little go with Pi.ai myself, and I found it to be a bit obsequious, like a friend who just agrees with everything you say.

Prof Reid, aka my other half, says that's how it has been designed. "What you call obsequious, I see as friendly and supportive.

"I can see conversational AI being really valuable in a setting such as a care home, where people would get joy from reminiscing about the past with something that is knowledgeable. Or a call centre, where the AI can understand when a caller is getting frustrated, and react accordingly."

Or perhaps helping to keep thousands of relationships alive across the globe, by providing therapy to fraught football and baseball fans from Liverpool to Boston, and beyond.

1 year ago

90

1 year ago

90

English (US) ·

English (US) ·