ARTICLE AD BOX

By Max Hudson, Simona Weinglass, Mark Turner and Joel Gunter

BBC Eye Investigations

A global scamming network has robbed ordinary investors of more than a billion dollars. BBC Eye identified a shadowy network of businessmen who appear to be behind it.

First, you hear a phone ringing. An elderly man answers.

The caller introduces himself as "William Grant", from the trading firm Solo Capitals. He says he has a "great promotion" to offer.

The elderly man sounds vulnerable and confused. "I'm not interested, I'm not interested," he says.

But William Grant is persistent. "I only have one question," he tells the old man.

"Are you interested in making money?"

Jan Erik, a 75-year-old pensioner in Sweden, is about to get scammed - again. The call was made from the offices of Solo Capitals, a purported cryptocurrency trading firm based in Georgia. The recording is hard to listen to - not only does the elderly man, Jan Erik, sound muddled, he tells the caller he has already lost one million Swedish Krona (about £80,000) in trading scams.

But the caller already knows this. And he knows it makes the pensioner a good target for a follow-up "recovery scam". He tells Mr Erik that if he hands over his card details and pays a €250 deposit, Solo Capitals will use special software to track his lost investments and get his money back.

"We will be able to recover the whole amount," William Grant says.

It takes him a while to wear Jan Erik down. But after about 30 minutes on the phone, the pensioner begins reading out his credit card details.

The audio recording was saved by the company under the file name "William Sweden scammed". The BBC obtained the file from a former employee, but the company had not tried hard to hide it. In fact, it had handed it out to new recruits as part of the company training package.

This was a lesson in how to scam.

The scam

For more than a year, BBC Eye has been investigating a global fraudulent trading network of hundreds of different investment brands that has scammed unwitting customers like Jan Erik out of more than a billion dollars.

Our investigation reveals for the first time the sheer scale of the fraud, as well as the identities of a shadowy network of individuals who appear to be behind it.

The network is known to police as the Milton group, a name originally used by the scammers themselves but abandoned in 2020. We identified 152 brands, including Solo Capitals, that appear to be part of the network. It operates by targeting investors and scamming them out of thousands - or in some cases hundreds of thousands - of pounds.

One Milton group investment brand even sponsored a top-flight Spanish football club, and advertised in major newspapers, lending it credibility with potential investors.

In November, BBC Eye accompanied German and Georgian police on call-centre raids in the Georgian capital Tbilisi. On the computer screens, we saw row after row of British phone numbers. We phoned several and spoke to British citizens who told us they had just invested money. On one desk, there was a handwritten note with a list of names and useful details for the scammers: "Homeowner, no responsibilities"; "50k in savings"; "From Poland, British citizen"; "50k in stocks."

Next to the name of one British man, a note said: "Savings less than 10K, very pussy, should scam soon".

Milton group brands had office space in this downtown Kyiv office building. (Alexander Mahmoud/DG)

The majority of victims sign up after seeing an ad on social media. Within 48 hours typically they receive a phone call from someone who tells them they could make returns of up to 90% per day. On the other end of the phone there is usually a call centre with many of the trappings of a legitimate business - a smart, modern office with an HR department, monthly targets and bonuses, awaydays and competitions for best salesperson. Some call centres play pumping music in the background. But there are also elements you won't find in a legitimate business - written guidance on how to identify a potential investor's weaknesses and turn those weaknesses against them.

From their first phone call, victims can be directed into regulated companies or sometimes unregulated, offshore entities. Some victims who signed up to regulated brands within the Milton group are directed by their broker to place trades designed to lose the customer money and make money for the broker - a practice which is illegal under UK regulations. Some victims are instructed to download software that allows the scammer to remotely control their PC and place trades for them - also illegal. And according to former employees of Milton group brands, some customers think they are making real trades, but their money is simply being siphoned away.

"The victims think they have a real account with the company, but there isn't really any trading, it's just a simulation," said Alex, a former employee who worked in a Milton group office in Kyiv, Ukraine.

In order to better understand how the scam works, the BBC posed as an aspiring trader and contacted Coinevo, one of the Milton group's trading platforms. We were connected to an adviser who gave the name Patrick, and told us we could make "70% or 80% or 90% as a return in one single day". He told us to send $500 worth of Bitcoin as a deposit to begin trading with.

Patrick pressed our undercover trader to provide a copy of their passport, and after providing a fake copy we were able to continue to operate the account for about two months before Coinevo appeared to detect the fake. At that point, Patrick wrote to us by email, swearing at us and cutting off contact.

But the BBC's deposit money was already in the system. We were able to track it as it was divided up into small fractions and moved through many different Bitcoin wallets, all seemingly associated with the Milton group. Experts told the BBC that genuine financial institutions do not funnel money in this way. Louise Abbott, a lawyer who specialises in cryptocurrency and fraud, examined the flow of the money and said it suggested "large-scale organised crime". The reason the money was spread over various different bitcoin wallets, Abbott said, was to "make it as complicated as possible and as difficult as possible for either you, or the victim, or us as lawyers to find".

The perfect target

The victims of these telephone trading scams often have their financial and social circumstances used against them. People who reveal large savings pots are pushed to make large investments. People who are lonely are befriended by the scammers. As a recent retiree, Jane (whose name we have changed for this story) was a perfect target. She had just taken voluntary redundancy and had a lump sum of nearly £20,000 that she thought, invested wisely, could supplement her pension in the years to come. In June 2020, during the first lockdown, she saw an ad online for a company called EverFX.

At that time, EverFX was one of the main sponsors of the top-flight Spanish football team Sevilla FC. The club's stars had advertised the trading platform on social media and - Jane checked - it was regulated by the UK's Financial Conduct Authority.

Jane sent EverFX a message through their website and was called back and connected to someone she was told was a senior trader. He told her he was calling from Odessa, in Ukraine, and his name was David Hunt. His accent sounded Eastern European, Jane said, but she couldn't place it. She liked him instantly.

"He really knew his stuff, he knew how all the markets worked," she said. "I really got into it."

Jane lost her retirement fund. "I felt so humiliated," she said. "I didn't want to be on the planet anymore." (Joel Gunter/BBC)

Soon they were speaking nearly every morning, and Jane was revealing specific things she needed money for - expensive repairs to her roof, a buffer for her pension. Hunt used them against her, she said, telling her certain trades would "get her that roof" and "help her future".

Over the next few months, Jane invested about £15,000. But her trades weren't doing well. Hunt advised her to withdraw her money and invest with a different trading platform, BproFX, where she could get better returns.

By that point, Jane fully trusted David Hunt. "I felt like I knew him well and I thought he had my interests at heart," she said, welling up. "So I agreed to move with him."

What she didn't know was that BproFX was an unregulated, offshore entity based in Dominica. In reality, EverFX's UK regulatory status did not stop it from scamming British citizens, but the move over to BproFX would strip Jane of even the scant protections she might be afforded under UK law. The BBC found several victims who were moved to unregulated companies in this way.

In September 2020, Jane agreed to put £20,000 into BProFX, and Hunt coached her through various trades over the next few months. But somehow she kept losing money.

Other victims told the BBC they were scammed this way. Londoner Barry Burnett said he started investing after seeing an ad for EverFX, but after a few early wins, he suddenly lost more than £10,000 in 24 hours. The adviser pressured him to put in another £25,000 to trade himself out of his black hole.

"I must have got at least half a dozen calls in the space of about two hours," Barry said. "People begging me to put more money in."

Jane faced similar pressures from David Hunt. "He kept telling me that the more I put in the more I can recover," she said.

Instead, both finally decided to call it quits. Barry had lost £12,000, Jane £27,000.

"I'm horrified, numb," Barry said. Both made dozens of phone calls, chasing their losses, but with no results. David Hunt stopped answering Jane's calls. She knew she had lost everything.

"The day I realised was my birthday," she said. "It was the pandemic, and my family had organised a little outdoor get together and brought me a cake, and I was trying to be happy but I just felt so humiliated. I felt like I didn't want to be on the planet anymore."

It would be months before she could muster the courage to tell anyone what she'd done.

Putting the pieces together

The operations of the Milton group have been investigated before, by the Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter and others, but the BBC set out to identify the senior figures behind the global scam.

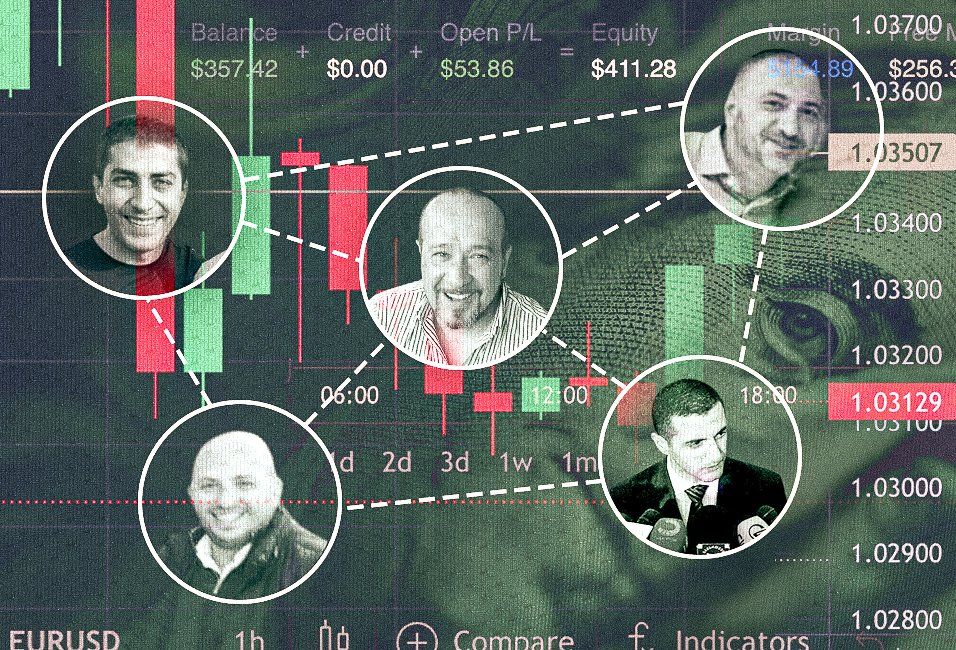

We began by combing through publicly available corporate documents to map the connections between companies in the Milton group. Five names appeared again and again, listed as directors of the Milton trading platforms or supporting tech companies - David Todua, Rati Tchelidze, Guram Gogeshvili, Joseph Mgeladze, and Michael Benimini.

We plugged the five names into the Panama Papers, a massive 2016 leak detailing offshore companies, and discovered that four of them - Tchelidze, Gogeshvili, Mgeladze and Benimini - were listed as directors or senior figures within a group of linked offshore companies or subsidiary companies that pre-dated the Milton group.

Many of these non-Milton companies led back in some way to one figure: David Kezerashvili, a former Georgian government official who served for two years as the country's defence minister.

David Kezerashvili, a former defence minister of Georgia, appears to be involved in the Milton scam. (Alamy/BBC)

Kezerashvili was dismissed as defence minister and later convicted in absentia for embezzling more than €5m of government funds. By the time of his conviction, he was living in London and the UK turned down a request from Georgia for his extradition.

There were no publicly available documents linking Kezerashvili to this pre-Milton network, but when we looked at the Panama Papers, his name came up again and again, identifying him as either the founder of the parent companies in the network or as one of their initial shareholders. Behind the scenes, Kezerashvili appeared to be at the centre of that network.

When it came to the Milton group, there was similarly no publicly available documentation linking Kezerashvili to the scam companies, and there was no evidence that he had any direct financial interest in the Milton brands.

But several former employees of Milton-linked companies told us confidentially that they had had direct dealings with Kezerashvili and knew him to be involved in the Milton group.

Kezerashvili has frequently promoted the scam trading platforms on his personal social media accounts. On the business networking site LinkedIn, he has used his account almost exclusively to promote jobs and share posts about Milton-linked companies.

The BBC was able to find a number of other pieces of evidence linking the former defence minister to Milton brands. Several companies owned by Kezerashvili used a private email server on which the only other users were Milton group companies. His venture capital firm, Infinity VC, owned the branding and web domains for companies that provided trading platform technology to the scammers.

Kezerashvili also owns a Kyiv office building that was home to both the scam call centre selling EverFX and the tech firms that provided the software - offices which were raided by police in November. He also owns a Tbilisi office block that contained some of the same tech firms.

When the BBC examined social media profiles belonging to the four senior Milton group men, it became clear from pictures posted of wedding parties and other social events that they all had close social ties to Kezerashvili. Kezerashvili is Facebook friends with at least 45 people linked to the Milton group scams, and one of the four senior figures identified by the BBC is his cousin.

The BBC tracked Kezerashvili to his £18m London mansion and asked to speak to him, but we were told he wasn't available. He told the BBC via his lawyers that he strongly denied any involvement with the Milton group, or that he gained financially from scams. He said that EverFX was to his knowledge a legitimate business and his lawyers argued other connections we have found to the people and IT behind it "proved nothing".

Scam victims download a trading platform, but some are never placing real trades at all. (Joel Gunter/BBC)

Mr Chelidze and Mr Gogeshvili also strongly denied our accusations, saying that EverFX was a legitimate, regulated platform. They denied knowledge of Milton or any connection between EverFX and the brands we identified, which they suggested had misused EverFX's source code and brand to confuse users. They said EverFX had never had a crypto wallet and had no control over how its third-party payment processors directed funds.

Mr Mgeladze also denied our accusations, telling us that he has never owned any call centres fraudulently mis-selling investments and has no knowledge of the Milton group.

Mr Benimini did not respond to our questions.

EverFX denied our allegations, saying that they were a legitimate and regulated platform where risks were fully explained. They said that they had investigated Barry Burnett's case and found that he was responsible for his losses.

In Jane's case, they told us her losses were as a result of her moving to an unconnected company. They said that they had fully cooperated with the FCA and there were no outstanding UK regulatory complaints.

Sevilla FC told the BBC only that once their contract with EverFX ended, they had no more contact with the company.

Fraud accounted for more than £4bn worth of crime in the UK last year, and online investment scams are thought to be worth hundreds of millions of pounds per year. But British police have faced criticism from victims over what they see as a lack of action against scammers on behalf of British nationals.

Jane went down various routes, at home and abroad, in pursuit of her lost retirement funds, but got nowhere. The UK's City of London Police took a report from her but "nothing came of it", she said. Her bank was not able to help either, "apart from writing a few letters".

"And why should they, really?" she said, with a sad shrug.

So she did the only thing she could think of. She went to a dozen online review websites and wrote reviews of the trading brands that had scammed her.

"I just wanted to warn anyone else who might fall for it," she said.

"I put a lot of effort into that. I hope someone sees it."

1 year ago

22

1 year ago

22

English (US)

English (US)