ARTICLE AD BOX

Image source, Leviathan

Image source, Leviathan

By Chris Baraniuk

Technology of Business reporter

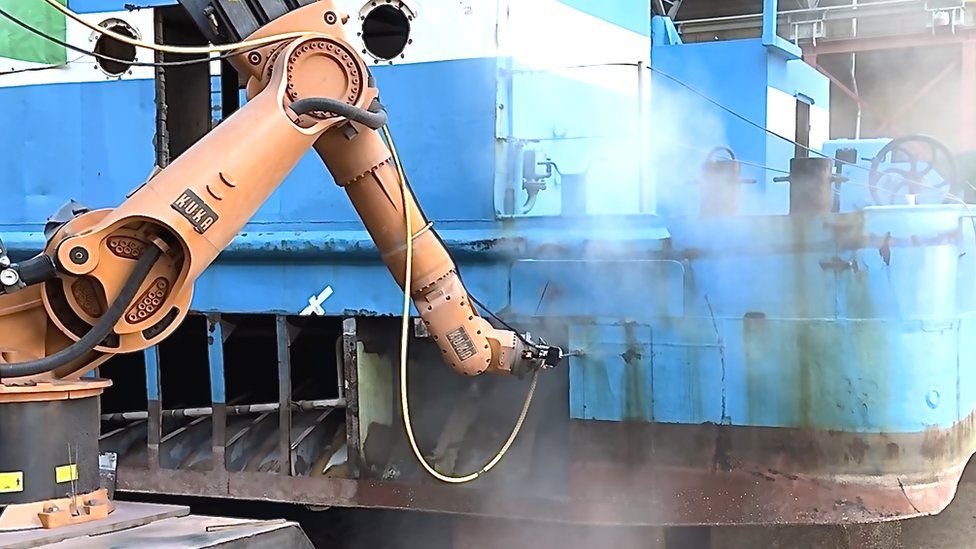

A huge robotic arm, wielding a waterjet powerful enough to slice through steel, swings into action.

It is chopping up the hull of a large ship. The structure, which withstood the power of the sea for decades, yields easily to the cutting jet. Before long, the robot has sliced out a big rectangle of steel.

Its task complete, the machine silently moves on to the next section.

"You can have robots starting at the bow and the stern, and two points in the middle, and working towards each other," says Bryce Lawrence, operations director at Leviathan. The firm, based in Germany, plans to use a team of robots to dismantle huge ships so that the steel can be recycled.

Today's shipbreaking industry is one of the dirtiest and most exploitative in the world.

When mammoth vessels retire from years of ferrying cargo such as consumer goods, or oil, between continents, they often end up on a heavily polluted beach somewhere in South Asia. There, workers use fossil fuel-powered torches to painstakingly dismantle the ships. Protective clothing is scarce. Fatalities are not.

Image source, Getty Images

Image caption,Traditional shipbreaking is labour intensive and often dangerous

Contaminants, including heavy metals, often get washed into the sea from these beaches. Workers and local communities are frequently exposed to dangerous materials including asbestos. During the next decade, 15,000 ships will require recycling - more than double the volume of the past decade, estimates Bimco, the Baltic and International Maritime Council.

Leviathan and other companies are trying to find ways of doing this work much more cleanly and safely. Still, there are no guarantees that they will be able to compete with the dirt-cheap yards of South Asia.

"Compared to traditional ship recycling, we're very, very low carbon," says Mr Lawrence as he explains how machinery at Leviathan's Stralsund facility on Germany's Baltic coast will be powered by electricity, not on-site fossil fuels, and that recovered steel will be transported to mills around Europe on electrified trains. Commercial operations are expected to start in the coming months, he adds.

The firm's prototype system is a mash-up of established technologies. The robot arms are the sort that toil in car factories, for example, and the waterjet is manufactured by ANT AG, another German firm.

This device blasts a mixture of water and sand at high pressures - a technology so precise that it is used by bomb disposal experts to cut the fuses out of bombs.

"Somebody has to approach the bomb, put the manipulating system on," says Till Weber, ANT AG's general manager, "then go as far away as possible." Mercifully, in such situations the jet can be operated from a distance of half a kilometer. It is currently in use in Ukraine, adds Mr Weber.

Image source, ANT

Image caption,The waterjet is precise enough to cut into unexploded bombs

When it comes to ship cutting, such a system requires far fewer workers than traditional shipbreaking does, and Mr Lawrence argues that it could one day complete the job much faster. Computer software being developed by Leviathan will automatically plan how to chop up a vessel as efficiently as possible.

On the other hand, there's a cost to all this and the robot arms must be properly mounted on special rigs fixed to a dry dock. You can't just plonk them on a beach.

Sefer Gunbeyaz at the University of Strathclyde has studied workers' exposure to toxic materials at shipbreaking facilities in the UK and Spain. Even in these countries, exposure - particularly to lead and iron particles - was "worrying", he and colleagues found.

"It's a promising start," he says, of the waterjet-based system in Germany. However, he notes that contaminants in the water used for cutting up ships must still be carefully managed.

Mr Lawrence explains that the Stralsund facility will feature a containment area designed to capture jet water and toxic substances that have been blasted off the ships. Once carefully decontaminated, this water can be reused for further cutting.

Elegant Exit Company, headquartered in The Netherlands, also says it can dismantle ships responsibly. Earlier this year, it began recycling the Wan Hai 165, a 160m-long container vessel.

The company uses gas-fuelled cutters at its Bahrain facility, but says that it removes hazardous materials before processing ships into large pieces of steel, of up to 25 tons, for transportation.

"We de-Lego a ship," says a spokeswoman, explaining that the idea is to safely disassemble each vessel, part by part. The firm will evaluate waterjet, plasma and hydraulic mechanical cutters in the future.

Image source, Elegant Exit Company

Image caption,Elegant Exit is breaking up this 160m long container ship

Recycling ships has been a dirty business for too long, says Ingvild Jenssen, founder and director of Shipbreaking Platform, a non-governmental organization that monitors the industry.

"What is even more shocking is that you have a whole shipping sector that is well aware of the problems," she adds.

Some ship owners attempt to send vessels from Europe to South Asian shipbreaking yards despite such exports being illegal. A BBC investigation in 2020 revealed that three oil rigs detained by the Scottish Environmental Protection Agency (Sepa) in 2018 had been earmarked for dismantling on a beach in India.

Two of the structures have since been broken up at an EU-approved yard in Turkey. "[The third rig, Ocean Princess] has not been dismantled and recovered yet as it was only exported to Turkey in May 2023," says Colin Morrow, of Sepa.

Improved documentation of the hazardous materials contained in a vessel could help recyclers process it appropriately, suggests Ms Jenssen.

Kuishuang Feng at the University of Maryland agrees and adds that ship owners could also be charged a levy when purchasing a vessel, redeemable if it is later recycled safely.

Both Mr Feng and Ms Jenssen say current legislation, including the recently ratified Hong Kong Convention, does not go far enough towards making shipbreaking sustainable. However, a spokeswoman for the International Maritime Organization argues that the convention will reduce the environmental impacts of ship recycling.

High-tech solutions could make a difference. Mr Lawrence says that Leviathan hopes to license its system to other shipbreaking yards - though he insists that he would only allow this in safe, controlled environments with the same capacity for capturing hazardous substances that he says is in place at Stralsund.

As it stands, the situation in many South Asian yards remains one of "constant exploitation", argues Jenssen. "You have workers that go to work - and they're not coming home."

2 years ago

65

2 years ago

65

English (US) ·

English (US) ·