ARTICLE AD BOX

BBC

BBC

Reef's father believes his son - seen here with a baby cousin just days before was killed - wanted children

Increasing numbers of bereaved parents in Israel are asking for sperm from the bodies of their sons - many of them soldiers - to be extracted and frozen. Some rules on the procedure have been relaxed in the wake of the 7 October Hamas attacks, but families are angry and frustrated about the lengthy legal processes they face.

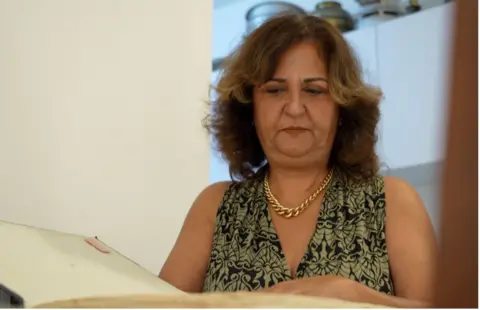

Avi Harush’s voice trembles as he recalls the moment he learned his 20-year-old son, Reef, had been killed in combat on 6 April 2024 in the Gaza Strip.

The military officers who came to his door also presented him with a decision. There was still time to retrieve Reef’s sperm – was the family interested?

Avi’s answer was immediate. Reef “lived life to its fullest”, he says. “Despite the horrible loss, we choose to live.”

“Reef loved children and wanted kids of his own - there’s no question about it,” he adds.

Reef had no wife or girlfriend. But as Avi began to share his son’s story, several women got in touch, offering to bear Reef’s child.

He says the idea is now his “life’s mission”.

Avi says the possibility of a child for his son Reef "gives us something to hold on to”

The family is among a growing number who have frozen sperm since the 7 October Hamas attacks on Israel, in which about 1,200 people were killed and 251 others were taken back to Gaza as hostages.

Israel launched a major military operation in Gaza in response, in which more than 39,000 Palestinians have been killed, according to the Hamas-run health ministry. About 400 Israelis have also been killed in the war.

Since 7 October, sperm has been retrieved from nearly 170 young men - both civilians and soldiers - according to the Israeli health ministry. It is roughly 15 times the figure for the same period in previous years.

The process involves making an incision in the testicle and removing a small piece of tissue, from which live sperm cells can then be isolated in a lab and frozen.

Success rates for retrieving the cells are highest if it is done within 24 hours of death, though they can live for up to 72 hours.

In October, the Israeli health ministry waived a requirement for parents to obtain a court order to request the procedure. The IDF says it has become more proactive in offering it to bereaved parents in recent years.

But while it has become easier to have sperm frozen, widows or parents who want to use it in the conception of a child have to demonstrate in court that the dead man wanted to have children. The process can take years, particularly for bereaved parents.

Rachel Cohen says she and her husband “faced so much opposition" as they tried to bring about a child for their dead son Keivan

The first parents in Israel to preserve and use their dead son’s sperm were Rachel and Yaakov Cohen, whose son Keivan was shot dead by a Palestinian sniper, according to the IDF, in 2002 in the Gaza Strip.

Their granddaughter, Osher - born from his sperm - is now 10 years old.

Rachel describes a moment after Keivan’s death when she felt his presence: “I went to his closet. I wanted to find his smell. I even smelled his shoes,” she says.

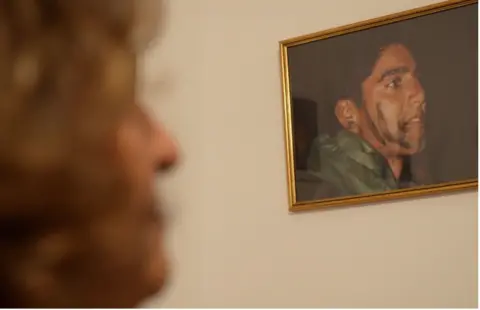

“He spoke to me from his photo. He asked me to make sure he has children.”

Rachel says they “faced so much opposition”, but eventually secured a ground-breaking legal decision, after which she advertised for a potential mother for her son’s child.

Irit (right) says Osher (left) knows who her father was but is not being raised to be a “living monument”

Irit - who did not share her surname to protect the family’s privacy - was among dozens of women who responded.

She was single. She says she was assessed by a psychologist and a social worker, and then, with court approval, began fertility treatment.

“Some say we're playing God. I don't think that's the case,” she says.

“There's a difference between a child who knows their father and one conceived by a sperm bank donation,” she adds.

Osher knows her father was killed in the army. Her room is decorated with dolphins. She says she knows he loved them.

“I know they took his sperm and searched for a perfect mother to bring me to the world,” she adds.

Irit says Osher has grandparents, uncles and cousins from both sides. But she says she is raising Osther “normally” to ensure she “is not raised to be a living monument”.

Osher knows her father was killed while serving in the army and that he liked dolphins

Preserving sperm has “great meaning” to bereaved families, says Dr Itai Gat, director of the sperm bank at Shamir Medical Center – who himself performs the surgery.

“It’s the last chance to preserve the option of reproduction and fertility in the future,” he says.

He says there’s been a “significant cultural shift” recently towards greater acceptance of the process, but that the current rules have created a conflict in the case of single men.

Dr Gat says, for them, there is often no clear record of consent. This has left families already coping with grief in “a very difficult situation”, where the sperm has been frozen but they can’t use it for fertilisation.

Dr Gat says he has spent time with bereaved families and seen how freezing a loved one's sperm can bring some comfort

“We’re discussing reproduction, bringing a boy or girl into the world… that we know will be an orphan, without a father,” he says.

In the majority of cases, the deceased would not have known the mother of the child made using his sperm, he adds, and all decisions regarding the child, his education and future would be made by the mother.

He says he was previously opposed to preserving sperm unless there was clear consent from the deceased, but his view has softened since meeting families bereaved in the current war.

“I see how meaningful it is to them, how sometimes it gives them some comfort,” he says.

After a legal battle, Rachel placed an advert in a newspaper to look for a potential mother for a child for Keivan

Rabbi Yuval Sherlo, a prominent liberal rabbi who leads the Tzohar Center for Jewish Ethics in Tel Aviv, also says the consent of the deceased is an important consideration.

And he explains that two important principles in Jewish law are also involved – continuing a man’s lineage and burying the body whole.

Some rabbis say continuing the lineage is so important it merits the damage to the body tissue, he says, while others maintain the procedure should not take place at all.

Reuters

Reuters

The Israeli death toll from the 7 October attacks and the war that followed has made the issue of sperm retrieval more pressing for lawmakers

The current rules on the issue are guidelines published by the Attorney General in 2003, but are not enshrined in law.

Israeli lawmakers have attempted to draft a bill to create clearer, more comprehensive rules, but efforts have stalled.

People close to the process have told the BBC there has been conflict over the level of explicit consent that should be required from the deceased, and whether the child would receive the benefits normally given to the children of soldiers killed in service.

Israeli media have also reported disagreement between widows and bereaved parents over how much control parents should have over their sons’ sperm, especially if the widow does not wish to use it to have a child.

Those who have already frozen their sons’ sperm are worried that if legislation is eventually agreed, it will only address future issues of consent, and not prevent them from facing lengthy court battles.

For Avi, there is determination within his grief.

He looks through a cardboard carton, filled with diaries, albums and mementoes of his son.

He says he won’t rest until he can give Reef a child: “It will happen… and his children will receive this box.”

3 months ago

18

3 months ago

18

English (US)

English (US)