ARTICLE AD BOX

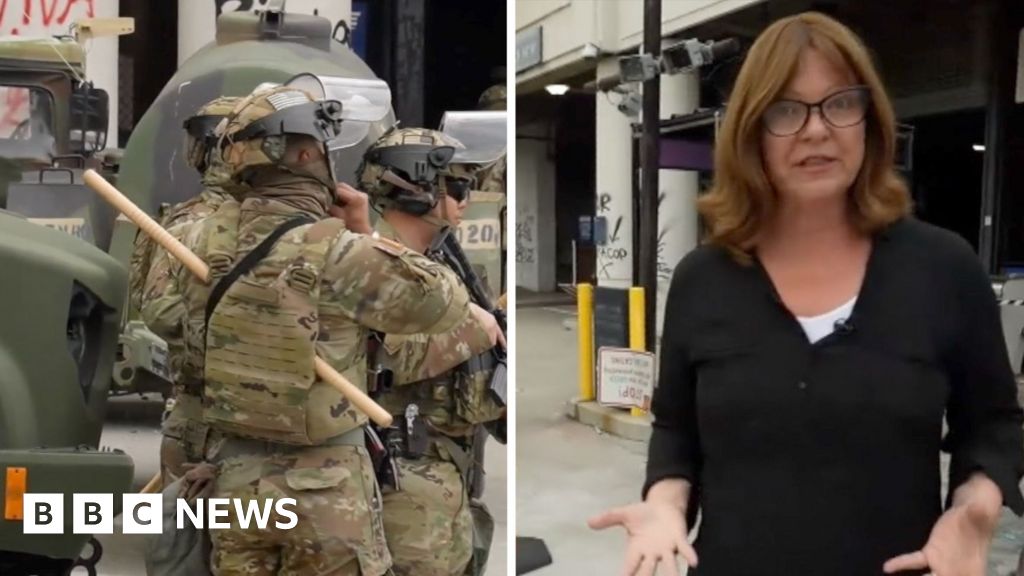

Poole, an ultra runner from London, has competed in the past two editions of The Speed Project

Poole, an ultra runner from London, has competed in the past two editions of The Speed Project"When the cops pull you over, be super nice," says Nils Arend.

"I personally have an issue with authority, but in The Speed Project you're representing all of us in every interaction.

"So be nice, be cooperative. And when they ask what you're doing just say, 'Oh, we're just a bunch of friends running to Vegas'.

"They don't need to know more or less."

Arend is sitting in a north London bar explaining the ground rules of one of the world's most sought-after ultra-running races.

Being friendly, but discreet, in the face of the law is part of the pre-race briefing he gives at The Speed Project (TSP), an unsanctioned, unsupported 350-mile race from Los Angeles to Las Vegas via Death Valley.

It has no website, no "register here" button, no rules, no official route, no spectators and, until a week before, no official start date.

It's a "Fight Club" of the running world created in the mould of its founder. Before he found marathon running after moving to Los Angeles in the mid-2000s, Arend organised a rave night in a borrowed brothel in Hamburg's red-light district.

Despite the race's underground status, the start line is filled with some of the world's fastest athletes, and the biggest brands.

How do they get there? Well, that's a long story, shrouded in secrecy.

Arend first ran the route in 2013 as a relay with five friends - three other men and two women. Competing in that format is now known as the original (OG) way to race.

Since then, though, three other categories have been added, including, incredibly, a solo class in which British ultra-runner James Poole has competed in the last two years.

"It's difficult to not sound holier than thou, preachy, or that everyone else who is doing their thing is wrong," says Poole who, in between wild camping in derelict buildings surrounded by used gun cartridges and fuelling himself entirely with food and drink from roadside gas stations, completed the 2023 race in just under 119 hours.

"But I do think that once you have got a box full of medals you don't ever look at and a collection of T-shirts that don't mean anything to you, then going off the grid is a purist way of doing something that you love."

Arend shares the same love of the leftfield. And an outright dislike for the staid approach to competitive distance running.

"When I moved to LA, I ran a couple of marathons," he says. "But I felt so out of place. I was like 'these are not my people'.

"So the next iteration of it all was for me to start to do my own things. We create a safe place for everybody to show up the way they are. No marathon can do that. They could. But they are not doing that. They are just running their own programme like it was 25 years ago.

"There are two fields of motivation as to why people are attracted to TSP.

"One is 'OK, I want to go there, perform and crush it' and the others are 'I am going to use TSP and its community to amplify my voice, my mission, the cause I am behind'. As long as it aligns with who our community is, then that is exactly who we are for."

Most of the world's biggest running brands want to be part of Arend's vision.

The Speed Project celebrated its 10th anniversary this year and the list of brands who have sent teams is a who's who of the sport, from Nike to Tracksmith, New Balance to On Running.

Their presence on the lowest of low-key start lines - the race begins at 04:00 at Santa Monica Pier - is one of many paradoxes in an event which both courts and shuns publicity at the same time.

Stripped of all the usual trappings of high-profile running races, TSP's desirability to big brands has actually sky-rocketed.

Poole knows more about that strange irony than most.

The 47-year-old's sponsors made a short film about the event in 2022, accompanying him with a campervan to help with refuelling, sleeping and navigation.

This year, though, he ran the event entirely unsupported, the only person in the field to do so - a decision even Arend thought was "crazy".

It meant Poole was responsible not only for running more than 500km through hugely variable conditions - he spent much of the 2023 event in a padded down jacket and trousers because of unseasonably low temperatures and snowstorms - he was also in charge of finding his way, his food, and his sleeping spots.

Competitors are responsible for their own route, nutrition, hydration and finding their own places to rest

Competitors are responsible for their own route, nutrition, hydration and finding their own places to rest"I've got a couple of niggles from TSP but I'm sure it'll be fine," he says.

It's less than two weeks after his return from Los Angeles, and Poole and I are on a 10k run along the Regent's Canal and his other regular running routes in east London.

After casually dropping into conversation the plan to run a marathon in a few days' time, Poole tries to explain the allure of the 350-mile TSP and a route that, on the face of it, is famous only for its featurelessness.

Part of his 2023 route took him down the Yermo Road - a 75-mile straight stretch of tarmac without a single turn.

"You run for six hours and you are on the same road," he says. "You do six more and then you're still on the same road.

"If you're doing about 75 miles a day as I was, then you spend the whole day on the same road without a single turn."

Paula Radcliffe used to count to 100 in her head on repeat during marathons.

"Can you imagine how many times I'd get to 100 if I did that?" Poole laughs. "I think the important thing is to just be present. And that is what's going on, I think, with Paula's counting to 100, you are not thinking about the thing in the future.

"You've got to be enjoying the moment as much as you can. If you start thinking 50 miles in that you've got 250 or more to go, that just blows your mind."

Poole, who took a camera with him on the race and captured some of the images in this article, continues: "The TSP route is kind of beautiful in a brutalist type way. Beauty is everywhere. It's just the way you see it. The gas stations are as ugly as sin but they're beautiful when you get there.

"For a British person, we don't have wide open spaces like that or the old Americana ghost-towns.

"I could, and did, sleep in derelict buildings, which is quite hard to do in the UK."

Is it not scary? "Yeah, a little bit," he says. "When you sleep in buildings with gun shells in there, you think: 'How safe is this?'

"Last year, I remember seeing a car full of bullet holes, but it had a bench seat in the back. I was so tired, I really considered sleeping in there it but decided it was a stupid idea.

"It was obviously used as shooting practice by people - can you imagine?"

At a glance, Arend's journey from organising underground raves in Hamburg to heading up an ultra-endurance race in Los Angeles might seem an unlikely one.

But he insists there is a link between the two.

"It's the same, it's an endurance sport of folks, a lot of whom have parted ways with the nightlife," he says. "Lots of folks who had issues, alcohol, drugs whatever, they find themselves in that sport and we're creating an environment where they feel understood."

Organiser Nils Arend previously put on rave nights in the red-light district of Hamburg

Organiser Nils Arend previously put on rave nights in the red-light district of HamburgPoole feels similar, insisting that TSP should be understood as a reset from society's norms. An extreme, yet mindful, desert retreat from the monotony of nine-to-five living.

"There's a sort of joy in being self-sufficient [at TSP], and looking after yourself and not needing anybody," Poole says.

"These days, everything is pretty easy, right. We live in a world of convenience, particularly in the UK and the US.

"You can have Deliveroo bring you takeaway. You don't have to leave your house.

"This is like the other extreme. No-one brings you anything. You don't get it, until you find it. And if its closed, that's the way it goes."

Poole should know.

There were routinely stretches of this year's race in which he went eight to 10 hours without an option to restock with food or water.

Arend also knows, and thrives, on such feelings of escape, and pushing the boundaries of physical endurance.

In fact, if rumours are to be believed, then going eight to 10 hours without food or water options will be a walk in the park compared with what he has planned.

Poole did the 2023 event solo and unsupported

Poole did the 2023 event solo and unsupportedPoole lets slip in our conversation that Arend is thinking of attempting a Speed Project-style race in November in Chile.

It will be similar to TSP in distance and ethos, but much more extreme given it would send runners across the entire Atacama Desert, one of the world's harshest environments.

A race across the Atacama would have zero resupply options. Teams would need to be entirely self-sufficient, carrying all their equipment in pick-up trucks because of the nature of the terrain.

Arend is coy about the question of what's next? "That's the really difficult question," he says. "We are exploring other elements.

"I'm always going on my own adventures and, similar to how TSP was born, if I come across an adventure that I think is worth sharing with the community, I will continue sharing that."

Poole is less equivocal.

If Arend brings the race to the Atacama, he'll be the first name on the teamsheet, regardless of the risks. Why?

"What I don't understand is the people who do the London Marathon again and again and spend the rest of their running career trying to shave five seconds off a time that no-one really cares about," he says.

"My answer to that is to stop chasing this thing that is not that important and go and do something that is exciting.

"There are lots of subtle reasons for not going to do these sort of things like TSP. But ultimately the pithy, slightly obtuse, answer to why do these things is just because you can. And if you can do it, then why not give it a go?"

2 years ago

41

2 years ago

41

English (US) ·

English (US) ·