ARTICLE AD BOX

By Tara McKelvey

BBC News, Annapolis, Maryland

Image source, CBS

Image caption, Diana and Jonathan ToebbeThey seemed to be living the most ordinary of lives, Jonathan and Diana Toebbe - professional, comfortable, unostentatious.

Their red-brick house in a posh part of Annapolis, Maryland - a coastal city of Romanesque churches and beaux arts-facades - held the comfortable clutter that comes with two children and two pitbulls, Sasha and Franklin, whose names are emblazoned on the front step welcome mat.

The neighbourhood streets are lined with cypress trees. Oyster shells are strewn in the grasses of a park close by, Quiet Waters. Yards are neatly mown, and the grass smells sweet. The US Naval Academy is nearby, as is a yacht harbour.

The peace of the place was broken on Saturday, when federal agents descended on the Toebbe house, from which they had followed the couple to Jefferson County, West Virginia.

This is where Mr Toebbe, 42, and his 45-year-old wife were attempting to commit treason, according to the US government.

The Maryland couple have been charged with allegedly trying to sell military secrets to a foreign government, for which they could face life in prison if found guilty.

As a preliminary hearing on the Toebbes case opens in Virginia on Wednesday, their story is being widely seen as that of a government worker, an engineer, who secretly wanted to be something more, a larger-than-life figure, a super-spy, and had fantastical ideas about how he could outfox the authorities, and the rest of the world.

It is an extraordinary case, rare in the field of national security, because of the access he had to valuable military secrets, and the lengths he went to in order to sell them. Mostly, though, it is striking because of the human factor: he was willing to risk everything, his own life, his wife, his family and the nation, in order to live out this fantasy.

The attempts at espionage began in April 2020 when, according to the justice department, Mr Toebbe, a US Navy employee, contacted an official who worked for a foreign government by sending them a package in the mail with a note saying he could provide them with information about nuclear submarines.

As an expert with security clearance working in the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, he claimed to have access to information on nuclear-propulsion systems used in submarines.

Image source, US Navy/Thiep Van Nguyen II

Image caption, The couple allegedly tried to sell secrets about US nuclear submarines to a foreign governmentThe government appears to be one that has friendly relations with the US: officials who work for the foreign government co-operated with US investigators while they were setting a trap for Mr Toebbe. This seemed to indicate that the foreign government was an ally, such as France, and not Russia or China. But no-one has confirmed which country was involved.

The FBI got hold of the package a few months later, in December, and dispatched its agents to pose as foreign officials to contact Mr Toebbe, saying they were interested in what he could offer.

Thus began many months of misadventure from the couple, with Mr Toebbe leaving classified files on SD memory cards at spots used by spies to deliver intelligence materials, known as dead drops. His wife acted as look-out, according to government charges.

The propulsion technology he was said to be trying to sell is one of the closest held military secrets and was at the centre of a high-stakes deal, one the US and UK had recently reached with Australia. According to investigators, Mr Toebbe smuggled documents out of work a few pages at a time to get past checkpoints.

"I was extremely careful to gather the files I possess slowly and naturally in the routine of my job, so nobody would suspect my plan," he wrote in a note to his supposed conspirator.

Clumsy efforts to hand off the goods included hiding an SD digital memory card in a half peanut-butter sandwich, or stashed in a pack of chewing gum, or covered by a Band-Aid wrapper in a refrigerator bag, court documents said.

For the peanut butter sandwich card, Mr Toebbe received $20,000 (£14,500) in cryptocurrency.

Mr Toebbe was skittish at first, but eventually seemed to become comfortable with the "foreign official" he was selling to, unaware it was the FBI.

He even appeared to grow fond of them, writing in a note: "One day, when it is safe, perhaps two old friends will have a chance to stumble into each other at a cafe, share a bottle of wine and laugh over stories of their shared exploits."

By the time they were arrested last week, a substantial paper trail had been collected, documenting their efforts at espionage.

Man of mystery

A week after their arrest, everything at the Toebbes' home was just as they had left it - the ceiling fan still spinning in the basement, a half-complete knitting project, a sock, on the sitting-room table. Neighbours were in shock.

Many wondered how a couple that seemed to have everything going for them could now stand accused of trying to sell some of the nation's military secrets to a foreign nation.

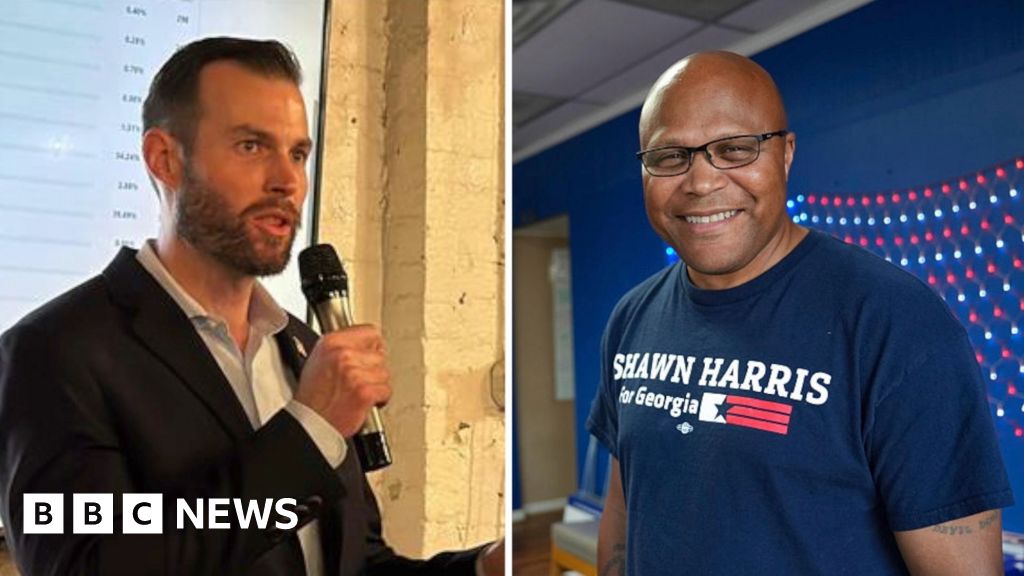

Image source, Reuters

Image caption, Mr Toebbe seen in federal court in West VirginiaAccording to neighbours, while the couple were not especially social, they were not secretive either.

Mr Toebbe had an interest in medieval weaponry and was active in a local chapter of an enthusiast organisation, the Society for Historic Swordsmanship. Mrs Toebbe, 45, had a PhD from Emory University in Atlanta and taught at a private school.

If blending in is a desirable trait for a spy, she did not fit the bill - she had bright purple hair that made her easily recognisable, a neighbour said. "She was supposed to be a spy, and not stand out."

Money and motive

With all of their personal and professional success, why would the Toebbes do this?

It is a bit of a mystery, said David Charney, an Alexandria, Virginia-based psychiatrist who has spent decades studying espionage cases. But, said Mr Charney, there are themes that are common in many similar cases.

Often, individuals are a bundle of conflicting impulses, Mr Charney said - usually involving wanting money, or perhaps having a thirst for revenge. Some are driven by a desire to prove that, however average they may appear, they are in fact extraordinary individuals, with a big secret.

Officials who work for the intelligence services, and study the psychology of betrayal, have come up with an acronym to describe such motives, MICE - money, ideology, compromise and ego. According to the officials, these are reasons that people commit treason.

Government prosecutors indicated that Mr Toebbe wanted money. According to an affidavit drawn up by federal investigators, he asked for $100,000, paid in cryptocurrency, in exchange for his nuclear secrets.

And there are suggestions that he and his wife may have had financial trouble. A magistrate judge, Robert Trumble, reviewed their financial declarations and said they could have court-appointed attorneys.

This may mean they were not wealthy, since they could not afford their own lawyers, but they were not destitute, either.

Image source, Reuters

Image caption, Mrs Toebbe has purple hairShe is now represented by two lawyers, Edward MacMahon of Middleburg, Virginia, and Barry Beck of Martinsburg. Mr Toebbe's lawyer is Nicholas Compton, an assistant federal defender in Martinsburg. The lawyers did not respond to requests for interviews.

Still, money would seem to be only part of the story, said Mr Charney, given, as he pointed out, that the Toebbes seemed to be relatively well-off.

"You look at their life, and see these pictures of a nice house, and you say: 'Gee, that's not so bad.' But it doesn't matter what you think. If they feel they're not measuring up, that can eat at them," he said.

Veteran spymasters also wondered how Mr Toebbe could have thought that his ploys would work. His techniques were not sophisticated, and they highlight the larger question of why an office worker, with no training in the field, would undertake such a risky operation.

"He's an amateur spy," says Jack Devine, a former senior CIA operations officer. "He had no training. They watch a couple TV shows, and they have no appreciation for what is needed."

"If you rely on spy movies to provide your tradecraft, you better really be good, or lucky," Mr Devine said.

Mr Toebbe, allegedly, was neither.

4 years ago

137

4 years ago

137

English (US) ·

English (US) ·