ARTICLE AD BOX

Image source, Legal Aid Society

Image source, Legal Aid Society

Nicole Mull of Legal Aid and filmmaker David Simpson make a mitigation video for a client

By Tom Brook

New York reporter

In the US, people accused of crimes are turning to short documentary-style videos about their lives to try and persuade judges, juries and prosecutors to look beyond the charges and see them as whole people deserving of redemption, and even leniency.

Augusta "Gussy" Clay has a sweet look as he sits with a child on his knee. Tanisha, his partner of 16 years, sings his praises. There are also pictures of "Gussy" in happier times in a playground with children and on the beach on a sunny day. He appears as a loving young man and someone who is cared for by those close to him.

All these images come not from a recording of a family get-together but from a mitigation video, a new digital tool that US public defenders are using to persuade judges to have empathy for their clients.

Produced with a high degree of professionalism, the videos can help tell an accused person's life story, providing additional context and presenting them in the best possible light. They're not like glossy Hollywood movies, but they can involve the use of music and elaborate production techniques. Others, like the one telling Augusta Clay's story, are more straightforward.

Clay had pleaded guilty to attempted robbery in the third degree, a low-level felony, and he was serving a 12-month sentence in New York City's notorious Rikers Island Prison for violating his parole.

At the time the video was made, he was in dire straits: he had cancer and cystic fibrosis. Incarcerated on Rikers Island at the height of the pandemic, when Covid was spreading through the jail, he begged to be let out early.

"I'm afraid of dying in prison," he says in the video.

There are no hard figures on how common mitigation videos are, perhaps because their use by public defenders in the US is still relatively new. But in a country that has one of the highest incarceration rates in the world, they are increasingly being seen by lawyers as an effective tool that can often reduce jail sentences.

Regina Austin, director of the Penn Program on Documentaries and the Law, is a pioneering figure in the use of mitigation videos, says they can be effective, because they de-stigmatise someone who is behind bars.

"We have in our mind's eye notions of what criminals look like, what they sound like, where they come from, and it's a picture, it's a composite. And one of the things that the mitigation videos can do, is to work on that image, to try to change that image in the mind, by providing context," she says.

Nicole Mull, who leads the Video Mitigation Project at the Legal Aid Society, America's oldest and largest law firm for low-income individuals, hopes these videos become more common.

"One of our big goals is to have more of these, so that our clients, public defender clients, can get the same representation as people charged with crimes that are people of means," she says. "And that's a very important piece of all of this."

Mitigation videos, she says, help judges see the humanity of her clients, "what drives them, what has put them in the position that they're in, and what we should be doing as society, rather than incarcerate them".

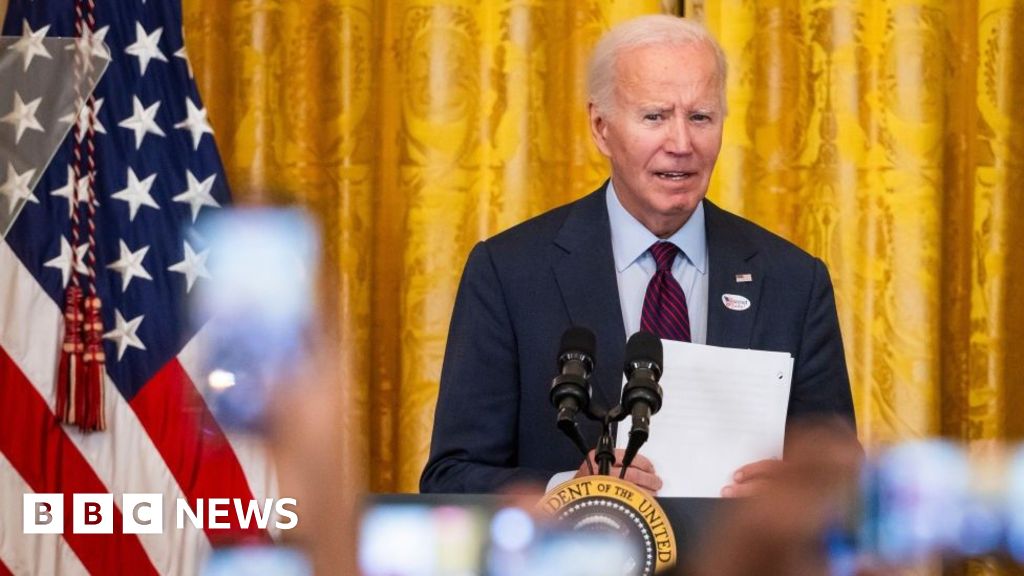

Image source, EPA

Image caption,Many have called for Rikers Island Prison to be shut down because of poor conditions and a series of inmate deaths in recent years

But there are critics opposed to the videos. Jennifer Harrison, executive director of the Victims Rights Reform Council, calls them a "slap in the face to victims".

"All empathy and emphasis is placed on the criminal. If they're going to be allowed to use these videos for the criminals, then victims should have that same luxury," she told the BBC.

A spokesperson for Legal Aid, however, points out that under New York law, crime victims can already deliver impact statements at sentencing, and mitigation videos are just another tool to provide context into an accused's life.

On 11 April 2020 Clay was finally released, albeit only two months short of his one-year sentence. He died a year later at the age of 39.

There's no absolute proof, but his lawyers fervently believe the mitigation video was pivotal in helping to get him out of jail and enabling him to spend his final days with his family.

Clay's video was put together by veteran New York filmmaker David Simpson, who has been involved in making them for almost five years.

"We try to capture a client, and their family, in their context, so we visit them in their homes, we go to their neighbourhoods, we capture images of the environment, where they live," he says.

But even supporters of these videos caution they can be counter-productive if they use music or are overly sentimental. "A bad mitigation video attempts to pull at the heartstrings. I want our videos to be used to enlighten. The videos are not to be used to manipulate," Austin says.

1 year ago

13

1 year ago

13

English (US)

English (US)