ARTICLE AD BOX

Christian Friedel plays Rudolph Höss, the Nazi commandant of Auschwitz

By Helen Bushby

Culture reporter

Director Jonathan Glazer says he borrowed techniques from reality TV, with a hidden crew and fixed cameras, for his film about Auschwitz concentration camp.

But his Oscar-nominated movie, The Zone of Interest, does not show the horrors of mass murder.

Instead, it focuses on the family living next door - camp commandant Rudolph Höss, his wife Hedwig and their five children.

Höss ran Auschwitz between 1940 and 1945, and used poisonous insecticide Zyklon B to gas prisoners.

An estimated 1.1 million were murdered there, one million of whom were Jews.

Meanwhile, just metres away, his family enjoyed their spacious house, plentiful food and manicured garden - separated from the camp by a concrete wall.

Glazer, who made the film near the site in Auschwitz, chose to hint at the terrible events inside the camp.

We hear muffled screams, gunshots and the churn of machinery, while smoke from the crematoria billows overhead.

Image source, A24

Image caption,It is possible the camp's prisoners could hear the Höss family in their garden

The family carry on next door as if nothing is happening, with Glazer using a fly-on-the-wall technique to film the actors.

"The phrase I kept using was 'Big Brother in the Nazi house'," he says.

Reality TV shows like Big Brother filmed people without visible camera crews, but with participants being watched at all times.

"The idea of eavesdropping felt like the way to show the drama - although there is no drama," Glazer tells the BBC. "It was a way of being in the house with them."

He rejected conventional filming methods, "where you get caught up in the actor and close-ups... they were the wrong thing for this".

Shot with natural lighting, it often looks like a documentary.

The film has been nominated for five Oscars, including best film, plus nine Baftas. Last year it won the Grand Prix at Cannes Film Festival.

Image source, A24

Image caption,Hedwig Höss steals clothes and make-up from Jewish prisoners

Footage of the actors was shot in a house not far from the original one, where the Höss family lived.

The director used 10 remotely operated cameras, while he and the crew watched from a nearby bunker.

He's correct in saying there is "no drama". The humdrum life of the family is not gripping in a conventional sense.

"There was no cosiness with the characters in the film-making," Glazer adds. "No funny, warm moments."

'Queen of Auschwitz'

We see Hedwig having friends over for coffee and being unpleasant to her housemaids, while the children play upstairs.

Meanwhile, Höss is in his study, discussing designs for a more efficient crematorium to murder as many people as possible.

The juxtaposition is deliberately shocking.

"We need to see all of that at once, to feel like we're in that house with them," Glazer says.

Hedwig, who calls herself "Queen of Auschwitz", also sneaks into her bedroom to try on a fur coat taken from a Jewish prisoner. She even smears on bright red lipstick after finding it in the pocket.

Image source, A24

Image caption,Friedel says Höss embodied "darkness" while being "a father, an ordinary, sometimes boring person"

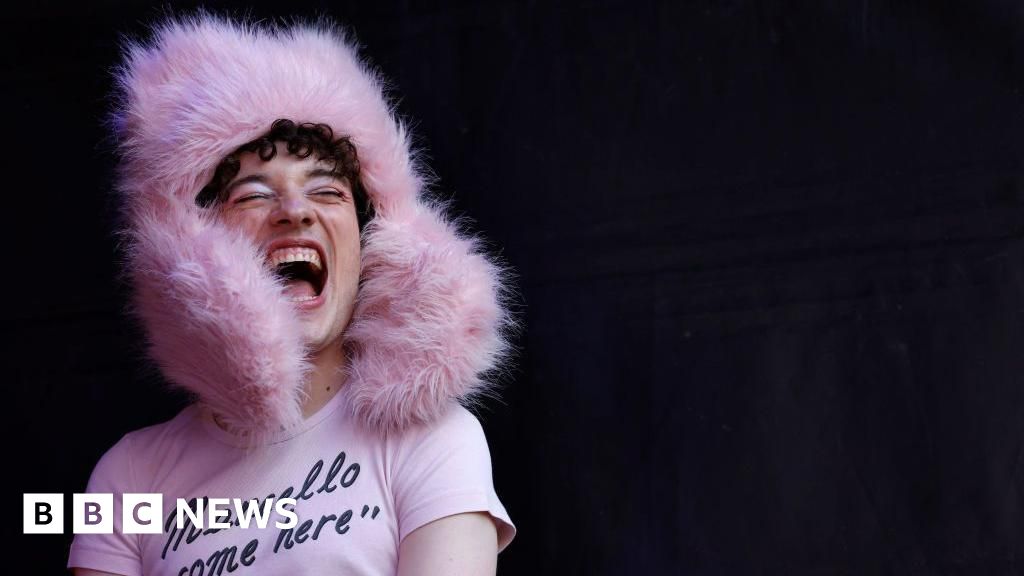

Christian Friedel agreed to play Höss despite previously turning down Nazi roles, including Adolph Hitler.

"Very often there are clichés of Nazis - brutal evils", he says.

He preferred Glazer's approach.

"To me, it makes sense to change the perspective, looking through a window to observe these characters. I was curious, how is it to act in this way?

"Jonathan said to us, 'Please don't act. Be'."

'A luxury situation'

Sandra Hüller, who plays Hedwig, is full of praise for Glazer's filming methods.

"It was really great to do - for me, personally, it was a luxury situation," she says.

Making films can sometimes bit "a little bit boring" - waiting around can mean you "lose energy".

Hüller, who is nominated for a best actress Oscar for Anatomy of Fall, says the fixed cameras and lack of crew meant they could record long scenes "without technical interruption".

"To feel that we have all the time in the world... we were allowed to make mistakes," she says. "I wish many projects could film in this way."

Image source, A24

Image caption,Jonathan Glazer (left) and the crew kept their distance from the set during filming

Most reviews for the film have been positive, with The Guardian's Peter Bradshaw saying it "pulls the banality of evil into pin-sharp focus".

Glazer, who is Jewish, is obviously aware that other movies have been made about Auschwitz, such as the award-winning Schindler's List, Sophie's Choice and Son of Saul.

But he "connected" with Martin Amis's novel The Zone of Interest, which he adapted.

"His book found a perspective that felt really extraordinary," the director says.

He did not want to feature Nazi brutality, because images of Auschwitz from documentaries, photographs and films are already "seared in our minds".

But that doesn't mean the audience escapes the camp's horrors.

Image source, A24

Image caption,Hedwig Höss, played by Sandra Hüller, shows her baby flowers, metres from mass murder

Glazer, whose other films include Under the Skin and Sexy Beast, knew "the sound would deliver the the perpetual atrocity going on - out of sight, but never out of mind for us".

Sound designer Johnnie Burn did "months of meticulous research".

"We viewed the project as two films: one you see, akin to a family drama or Big Brother; and one you only hear, coming from over the wall - the real narrative," he says.

The most difficult sound to reproduce was "the omnipresent, mechanical hum of the camp's machinery - a harrowing reminder of the workshops and the crematorium's furnace".

He also had the unenviable task of recreating how the camp's prisoners might have sounded.

"Believably capturing the sound of a life-ending scream is inherently challenging," he says.

'Satanic bellows'

Mica Levi's music features in certain moments of the film, including its opening, with a black screen while the score takes centre stage.

It provokes a variety of reactions.

"Some people find it quite peaceful, arcane - some people find it really alarming," the musician explains.

Hollywood Reporter describes the music as "a deep inhuman sound, like the roar of a satanic bellows", while Variety says it's "eerie in the extreme".

Levi calls it "a kind of question mark - it's not working to emotionally support the narrative of the characters".

Image source, A24

Image caption,Production designer Chris Oddy found period furniture that looked new enough for the film

Another key part of the film is the house itself - Höss had taken it from a Polish family and remodelled it.

Production designer Chris Oddy wanted to recreate it at Auschwitz, but was unable to.

The area is a Unesco world heritage site, so nothing could be disturbed or built within a 500m exclusion zone.

Despite this, Glazer was able to make his film in the area, called the Zone of Interest by the Nazis.

The Memorial and Museum for Auschwitz-Birkenau explains that this referred to an area around Auschwitz administered by the SS.

"To prevent prisoners from having contact with the outside world, and eliminate witnesses to their crimes, the Germans forcibly expelled approximately 9,000 residents from that area," it says.

'Holes for cameras'

The original house is still there, with a family living in it.

But it now doesn't look "new" enough to double for the Höss residence during World War Two.

"We got quite friendly with the family living there," adds Oddy, who visited them about six times during his research.

He managed to find a derelict building about 200m from the original house, which the crew used.

After four and a half months of replastering, decorating and sourcing furniture and plants, he had to embed the fixed cameras. "I just counted how many holes I had to make," he says.

Image source, Getty Images

Image caption,Rudolph Höss was hanged in Auschwitz, near the family home, after being found guilty of war crimes

Glazer concludes that his movie "looks into dark corners of human capacity", and is relevant today.

"I think what's inside this film is what we do to each other as human beings," he says.

"We see others as lesser than ourselves, different from ourselves. Somehow, step by step, that leads to atrocity.

"It's about the inherent violence in us - and how we need to evolve out of that state."

The Zone of Interest is released in UK cinemas on 2 February.

1 year ago

151

1 year ago

151

English (US) ·

English (US) ·