ARTICLE AD BOX

Image source, Dr Giridas PB

Image source, Dr Giridas PB

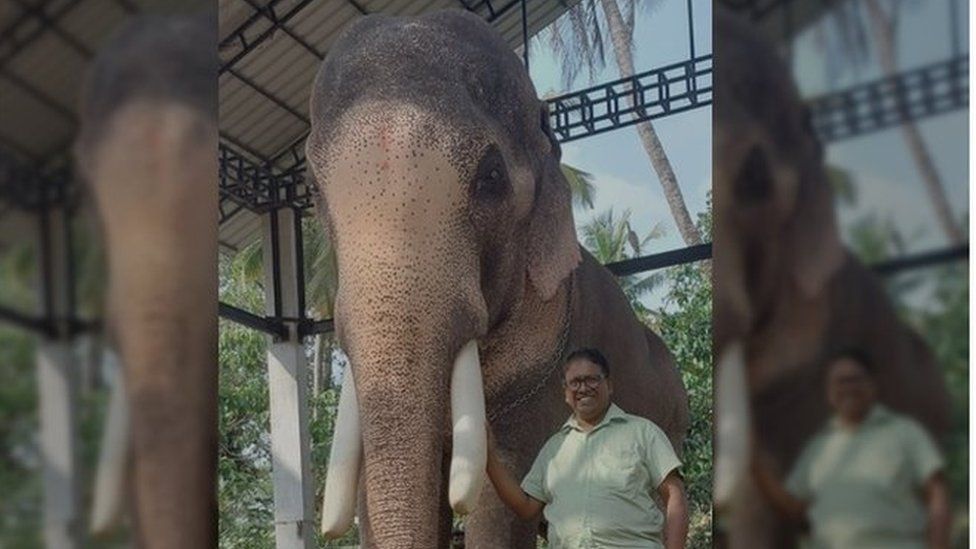

Ramachandran is often called the tallest captive elephant in India

A controversial elephant in the southern Indian state of Kerala is back in the news after a local temple bid a record amount for his participation in its annual festival. BBC Hindi's Imran Qureshi explains why the 57-year-old animal evokes both admiration and compassion.

Thechikottukavu Ramachandran is often called the tallest captive elephant in India, a claim that's hard to independently verify. What is beyond doubt is that he is 10.53ft (3.2m) tall, a majestic, imposing presence that looms large over his fellow pachyderms.

Ramachandran, who is owned by the Thechikkottukavu temple trust in Thrissur district, is one among hundreds of captive elephants in Kerala that are leased out for temple festivals and other programmes.

He has thousands of admirers - a fan page on Facebook which regularly posts photos and updates has 122,000 followers - and draws huge crowds at events.

But he is also notorious - critics says he displays violent tendencies and allege he has killed at least 13 people and two elephants over the past four decades. Thechikkottukavu temple officials, however, say that Ramachandran was not the direct cause of these deaths, which mostly occurred due to stampedes that broke out after he became agitated due to loud noises and other provocations at events.

Animal rights activists say that Ramachandran, who is blind in his left eye, shouldn't be forced to participate in public events.

"He is the tallest and most handsome of elephants. It is a marvel to see him from close quarters. But his majestic look has also become a curse," says Sreedevi S Kartha, who works with welfare organisation People for Animals.

Last week, 35 temple committees participated in an auction to bid for his presence at their festivals - Sree Vishwanatha Temple in Thrissur won by offering 675,000 rupees ($8,175; £6,759), a record bid.

"More people come to the temples when Ramachandran is present. That is why there is so much demand for him," says Bijoy PB, president of the Thechikkottukavu trust, adding that enthusiasm has picked up considerably after a lull in festivities due to the Covid pandemic.

In 2019, temple authorities ran into trouble when two people died after Ramachandran went berserk when crackers were burst near him in a congested neighbourhood near the famous Guruvayur temple in Thrissur. Two people died in the stampede that ensued.

The district administration then banned him from participating in the famous Thrissur Pooram temple festival, where Ramachandran sets off the festivities by symbolically pushing open the huge gates on the southern side of the Vadakkumnathan temple.

But they were forced to lift the ban after festival organisers, elephant owners and Ramachandran's fans protested - the Kerala Elephants Owners Federation said they wouldn't provide any tuskers for temple festivals unless Ramachandran was allowed to participate.

Image source, Dr Giridas PB

Image caption,Ramachandran has thousands of fans

The elephant's health condition routinely makes headlines - last September, the Kerala high court banned Ramachandran from participating in programmes until a committee examined him.

"The committee was set up and it was decided to parade Ramachandran just twice a month. Subsequently, a government order permitted the elephant to participate in parades twice a week," says MN Jayachandran, an animal rights activist who moved the court on grounds of cruelty.

He says the court also ordered four mahouts to be deployed around the elephant to ensure that he didn't come in contact with crowds.

Mr Jayachandran argues that Ramachandran is not only blind in one eye, he is also losing vision in the other eye and getting older.

But the elephant's champions claim that he is healthy.

"There is no problem with the other eye now. As per government rules, 65 years is the retirement age for elephants and Ramachandran is just 57," says Dr Giridas PB, Ramachandran's veterinarian and a member of the state's Animal Welfare Board.

He also insists that Ramachandran hasn't harmed anyone.

"When people burst crackers or make noise, the elephant gets hassled," he says.

Temple authorities also say too much is being made of the revenue Ramachandran brings in, and that a significant amount of this is spent on his maintenance, including food and his caretakers' salaries.

"In the last three years alone, we have spent close to two million rupees on his care, when we couldn't even earn from temple festivities due to Covid-19," says Bijoy from the Thechikkottukavu trust.

But others argue that the elephant's rights are being violated.

"[Parading elephants] is nothing but torture to the animals under the guise of offering to the deity," says Dr Jacob Cheeran, a retired veterinarian.

1 year ago

87

1 year ago

87

English (US)

English (US)