ARTICLE AD BOX

Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty Images

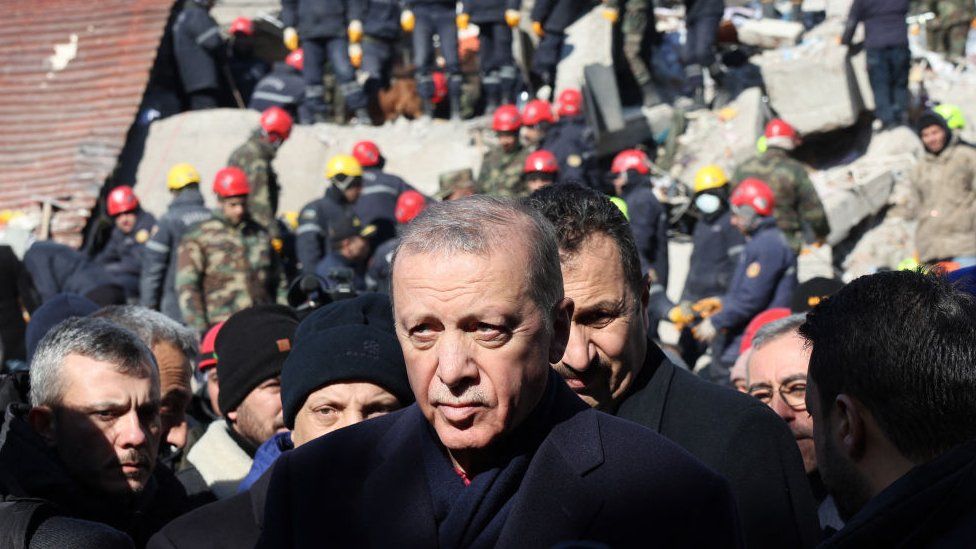

Opponents of President Erdogan say the heavy loss of life is down to politics

By Özge Özdemir & Paul Kirby

In Turkey and London

Turkey's most devastating earthquake since 1939 has raised big questions about whether such a large-scale tragedy could have been avoided and whether President Erdogan's government could have done more to save lives.

With elections on the horizon, his future is on the line after 20 years in power and his pleas for national unity have gone unheeded.

Recep Tayyip Erdogan has admitted shortcomings in the response, but he appeared to blame fate on a visit to one disaster zone: "Such things have always happened. It's part of destiny's plan."

Turkey lies on two fault lines and has earthquake building codes dating back more than 80 years. But last Monday's double earthquake was far more intense than anything seen since 1939. The first quake registered magnitude 7.8 at 04:17, followed by another of 7.5 dozens of miles away.

Delayed search and rescue

It required a massive rescue operation spread across 10 of Turkey's 81 provinces.

But it took time for the response to build and some villages could not be reached for days. More than 30,000 people from the professional and voluntary sector eventually arrived, along with teams from many other countries.

More than 6,000 buildings collapsed and workers from Turkey's Afad disaster authority were themselves caught up in the earthquakes.

Those initial hours were critical but roads were damaged and search and rescue teams struggled to get through until day two or day three.

Turkey has more experience of earthquakes than almost any other country but the founder of the main volunteer rescue group believes this time, politics got in the way.

After the last major earthquake in August 1999, it was the armed forces who led the operation but the Erdogan government has sought to curb their power in Turkish society.

Image source, Akut

Image caption,Volunteers from the Akut foundation have joined the government's main disaster agency in searching for survivors

"All over the world, the most organised and logistically powerful organisations are the armed forces; they have enormous means in their hands," said the head of Akut foundation, Nasuh Mahruki. "So you have to use this in a disaster."

Instead, Turkey's civil disaster authority now has the role, with a staff of 10-15,000, helped by non-government groups such as Akut, which has 3,000 volunteers.

The military's potential was now far bigger than in 1999, Mr Mahruki said, but left out of the planning it had to wait for an order from the government: "This created a delay in the start of rescue and search operations."

President Erdogan has accepted that search efforts were not as fast as the government wanted, despite Turkey having the "largest search and rescue team in the world right now".

'I warned them'

For years, Turks have been warned of the potential of a big earthquake but few expected it to be along the East Anatolian fault, which stretches across south-eastern Turkey, because most of the larger tremors have hit the fault in the north.

When a quake in January 2020 hit Elazig, north-east of Monday's disaster zone, geological engineer Prof Naci Gorur of Istanbul Technical University realised the risk. He even predicted a later quake north of Adiyaman and the city of Kahramanmaras.

"I warned the local governments, governors, and the central government. I said: 'Please take action to make your cities ready for an earthquake.' As we cannot stop them, we have to diminish the damage created by them."

One of Turkey's foremost earthquake engineering specialists, Prof Mustafa Erdik, believes the dramatic loss of life was down to building codes not being followed, and he blames ignorance and ineptitude in the building industry.

"We allow for damage but not this type of damage - with floors being piled on top of each other like pancakes," he told the BBC. "That should have been prevented and that creates the kind of casualties we have seen."

Image source, Reuters

Image caption,An international rescue team looks at the concrete floors of a collapsed building in Kahramanmaras

Under Turkish regulations updated in 2018, high-quality concrete has to be reinforced with ribbed, steel bars. Vertical columns and horizontal beams have to be able to absorb the impact of tremors.

"There should be adhesion between the concrete and steel bars and there should also be adequate transfer reinforcement in the columns," explained Prof Erdik.

Had all the regulations been followed, the columns would have survived intact and the damage would have been confined to the beams, he believes. Instead the columns gave way and the floors collapsed on top of each other, causing heavy casualties.

Quake tax mystery

Much has been made of failures in enforcing Turkey's beefed up building code and the justice minister has said anyone found to have been negligent or at fault will be brought to justice.

But government critics such as opposition CHP party leader Kemal Kilicdaroglu argue after 20 years in power President Erdogan's government has not "prepared the country for the earthquakes".

One big question is what happened to the large sums collected through two "earthquake solidarity taxes" created after the 1999 quake. The funds were meant to make buildings resistant to earthquakes.

One of the taxes, paid to this day by mobile phone operators and radio and TV, has brought some 88bn lira (£3.8bn; $4.6bn) into state coffers. It was even hiked to 10% two years ago. But the government has never fully explained where the money has been spent.

Urban planners have complained that rules have not been observed in earthquake zones and highlight a 2018 government amnesty that meant violations of the code could be swept away with a fine, and left some six million buildings unchanged.

The fines brought in billions of Turkish lira in taxes and fees. But when a residential building in Istanbul collapsed in 2019, killing 21 people, the head of the chamber of civil engineers said the amnesty would turn Turkish cities into graveyards.

More than 100,000 applications were made for an amnesty in the 10 cities currently affected, according to Pelin Pinar Giritlioglu of Istanbul University, who says there was a high intensity of illegal construction in the area.

"The amnesty played an important role in the collapse of the buildings in the latest earthquake," she told the BBC.

Image source, EPA-EFE/REX/Shutterstock

Image caption,Cities in 10 provinces with a population of more than 13 million were affected by Monday's quakes

"We cannot go anywhere by blaming each other and we should seek solutions," says Prof Erdik, who believes the problem goes beyond politics and lies in a system that allows engineers to go straight into practice after university with little experience.

Prof Gorur calls for the creation of "earthquake-resistant urban settlements" but for that there will have to be a shift in thinking, nowhere more so than in Turkey's most populous city.

"We have been warning about a possible Istanbul earthquake for 23 years. So the policymakers of Istanbul should come together and make policies to make people, the infrastructure, the buildings and the neighbourhoods resistant to an earthquake."

Polarised politics

President Erdogan has called for unity and solidarity, denouncing critics of the disaster response as dishonourable.

"I cannot stomach people conducting negative campaigns for political interest," he told reporters in Hatay, near the earthquake's epicentre.

Many of the towns and cities in the affected areas are run by his ruling party, the AKP.

But after 20 years in power, first as prime minister and then as an increasingly authoritarian, elected president, he leads a highly polarised country.

"We have come to this point because of his politics," said Mr Kilicdaroglu.

Campaigning for elections expected in May has not yet begun but he leads one of six opposition parties poised to announce a unified candidate in a bid to bring down the president.

Mr Erdogan's hopes of unifying the country ahead of those elections are likely to fall on deaf ears.

He has become increasingly intolerant of criticism and many of his opponents are in jail or have fled abroad. When an attempted coup against the president ended in bloodshed in 2016, he reacted by arresting tens of thousands of Turks and sacking civil servants.

The economy has been in freefall with a 57% inflation rate leading to a sky-high cost of living.

Among the government's first actions in response to the earthquake was temporarily blocking Twitter, which was being used in Turkey to help rescuers locate survivors. The government said it was being used to spread disinformation and police detained a political scientist for posting criticism of the emergency response.

Turkish journalist Deniz Yucel, who spent a year in jail in pre-trial detention, wrote from exile in Germany that the aftermath of the 1999 Turkish earthquake helped propel Mr Erdogan to power.

This latest disaster would play a part in the next vote too, he said, but it was not yet clear how.

1 year ago

31

1 year ago

31

English (US)

English (US)