ARTICLE AD BOX

Watch: preparing to deal with your period ahead of a polar expedition

By Harriet Bradshaw

BBC Climate & Science reporter

You're tied to co-workers, on a glacier, in icy conditions, and then you realise… it's that time of the month. What do you do?

Dealing with your period during fieldwork in the Arctic or Antarctic can be a challenge.

And yet talking about menstruation has remained taboo.

It's why it is on the agenda for the UK Polar Network (UKPN), a voluntary organisation which represents more than 400 early career scientists, and which is piloting a new workshop to tackle the issue head on.

"I've had so many of my friends and my peers come and say, 'God, I couldn't talk to anyone about this; I felt so uncomfortable; I felt scared at times'," explains Ellie Honan, a polar scientist in her 20s and co-president of UKPN.

"The reason that we want to bring these topics up, as simple and as basic as they might seem, is because historically toileting has actually been a barrier for people entering into fieldwork."

Image source, British Antarctic Survey

Image caption,Aurelia Reichardt, one of a growing number of female scientists working in Antarctica

A recent report uncovered how women working at Australia's Antarctic research camps felt they had to hide being on their period and ration tampons, amid widespread sexual harassment.

Its author, Prof Meredith Nash, says since her work there's been "significant momentum around making menstruation/toileting more accessible in polar fieldwork".

At the workshop, students are shown products from menstrual cups to period pants and how to use them in extreme environments.

Menstrual cups are really useful to polar researchers as you just take one with you rather than a bulk of tampons to last you months and months, but they can be fiddly to the newbie - unhelpful if you're halfway up a glacier and you've not practiced using one.

"I wonder if people don't do fieldwork and don't do science because they're worried about the taboo things, the things that people don't talk about," says 26-year-old PhD student Phoebe Noble.

She works on observations of atmospheric dynamics. High level science, but her response to the toileting talk is much more grounded.

"When I was 13, at school, you'd be smuggling your pads to the bathroom because you didn't want people to know that you're on your period. And then you think about going into the field where you don't know what conditions you're going to have, so having an open discussion… is really important."

Image source, UKPN

Image caption,Training for polar expeditions on Dartmoor

The British Antarctic Survey (BAS), the UK's national polar research agency, is launching a working party to produce tips on dealing with periods in polar conditions.

"You need to be understanding of your colleagues… enable dignity, privacy and rest as required," explains Rach Morris from BAS, who remembers having to change a tampon, whilst in a tent, in harsh conditions with colleagues and dogs present.

She was glad she knew her team well. She says being prepared and having understanding colleagues is key.

BAS has started reimbursing staff for period products, researching non-male clothing options and giving out free pee funnels to those who want them, to enable stand up weeing for safety purposes.

Personal hygiene, dehydration and the risk of getting UTIs are also discussed ahead of fieldwork, to stop people avoiding going to the loo if they're too shy or working too hard.

Image source, UKPN

Image caption,Aimee Shepherd: We want to see more women going to the Arctic and the Antarctic

"Historically developing a career for many women in BAS was challenging, primarily because research stations in the Antarctic were male only," Mariella Giancola at BAS explains.

But things are changing, with many women taking up roles from engineers to lab managers. Thirteen BAS women have now been awarded the polar medal for outstanding achievement.

"I can honestly say that we have made great progress, but we have a long way ahead."

And where things still need to improve, BAS now has an anonymous reporting tool. After all, working in such small and remote communities can put people off coming forward.

For UKPN, in answer to their recent question to members: "Have you ever been provided with or offered any training specific to dealing with menstruation in the field prior to a field campaign?" - of the 135 who answered, 88% answered "No".

The workshop also addresses the obvious environmental issues, too. Clever tips include concealing a zip lock bag in tape so you can't see inside, which turns it into a portable tampon carrier and bin.

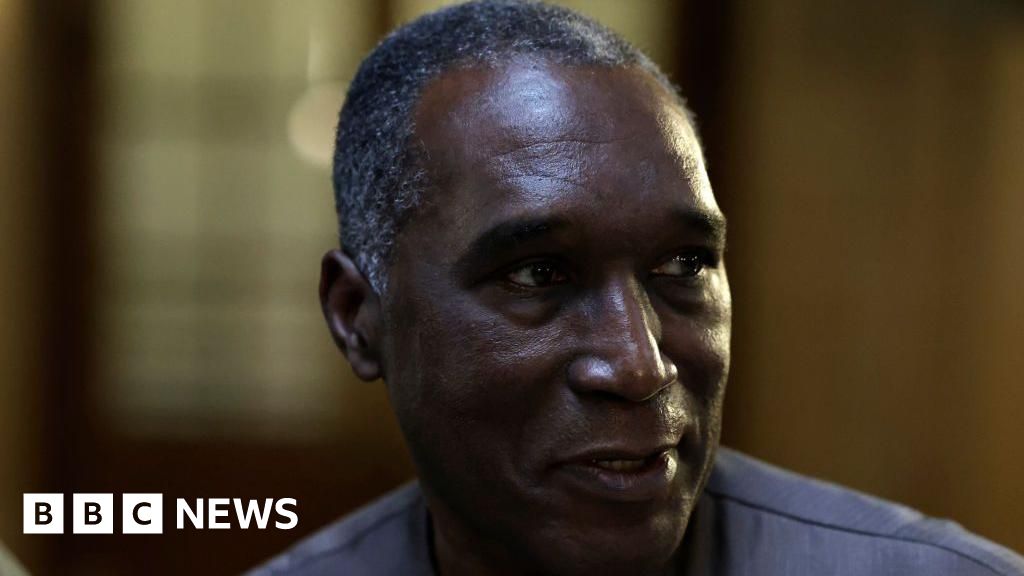

Image source, UKPN

Image caption,Andrew McDonald: Male colleagues need to know how to support their female colleagues

Andrew McDonald, a PhD student, is listening to the advice, because regardless of gender everyone attends the course.

"Having men and women in the room when talking about things like menstruation in the field has been really useful so that I can understand as a male colleague how to support teams and how to be a better leader," he says.

The workshop on personal hygiene is delivered as part of an overall survival skills course on Dartmoor, Devon. It's the first step in a four-year programme aiming to take 16 participants, all in their 20s and selected from across UK universities, on polar expeditions.

This cohort is largely women, with participants hoping to redress the historic gender imbalance.

"I'd absolutely love to see more women in science and going to the Arctic and Antarctic," 21-year-old marine biologist Aimee Shepherd says.

"It's been eye-opening," PhD student Maria Stroyakovski adds. "The insights that we've had, especially as women on this course, have been invaluable in pushing us a bit further to the frontlines of actually going on these expeditions."

Ellie emphasises: "Knowing where to go to the bathroom, and knowing where to change a tampon, and how to do that in a remote environment, shouldn't be hard."

1 year ago

57

1 year ago

57

English (US)

English (US)