ARTICLE AD BOX

By James Waterhouse

BBC News, Zaporizhzhia

Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty Images

Ukrainian emergency rescuers attend an exercise in case of a possible nuclear incident at Zaporizhzhia's nuclear plant.

It is relatively unusual in Ukraine for a government official to invite you on a short-notice trip.

It turns out it is more common for that invitation to come with very little detail.

The main reason for that is security - it is not exactly wise to publicise when a minister is going to be somewhere, especially when you are being invaded by another country.

We decided to accept, and soon found ourselves at an airfield near Kyiv, where we and other journalists were led onto a helicopter.

By this point we knew our destination was the city of Zaporizhzhia, and the subject was the growing danger from the region's nuclear power plant further south.

Within 30 seconds of the journey starting, I realised why we were offered anti-nausea tablets before taking off.

To stay undetected, the pilot keeps the helicopter around 10 metres off the ground, occasionally hurdling over electric powerlines.

There are endless fields of sunflowers. Some are in full bloom, some are wilting, past their best. Regardless, the harvest is fast approaching.

Then there is the dense woodland - thousands upon thousands of towering trees which come so close to touching the skids of the chopper.

You are left under no illusion of Ukraine's vast and rich landscape.

After landing in Zaporizhzhia, you are struck by two things: the more industrious skyline in comparison to Kyiv, as well as the humidity.

We end up at a supermarket car park where emergency workers are dressed in yellow hazmat suits. They are practising cleaning drills in the event of a radioactive contamination.

Image source, Getty Images

Image caption,Ukraine's last nuclear crisis was the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear incident, when a Soviet-era reactor exploded.

They are watched by senior officials, who are keen to see how ready the region would be in the event of a worst-case scenario.

"Of course we are concerned," Ukraine's Energy Minister Herman Halushchenko tells me. "The situation changed dramatically when the Russians started shelling the area on 5 August."

Ukrainian says the situation at the plant is "approaching critical".

Russian forces have occupied the site, Europe's biggest, since early March.

They have been urged to hand control back because of the dangers, and some staff there have told the BBC they're "being kept at gunpoint".

For the past two weeks there's been heavy shelling on and around the plant, with the sides blaming each other.

Nato is the latest international organisation to call for United Nations inspectors to be let into the Zaporizhzhia power plant, claiming its seizure posed a serious threat to Ukraine and neighbouring countries.

Officials say the plant could be cut off from power as Moscow tries to redirect electricity to Crimea, which it annexed eight years ago.

"It is impossible to ensure the safety of the nuclear power plant while the Russian occupying forces are there," says Denys Monastyrskyy, Ukraine's interior minister.

"It is the key concern that we all should understand," he adds.

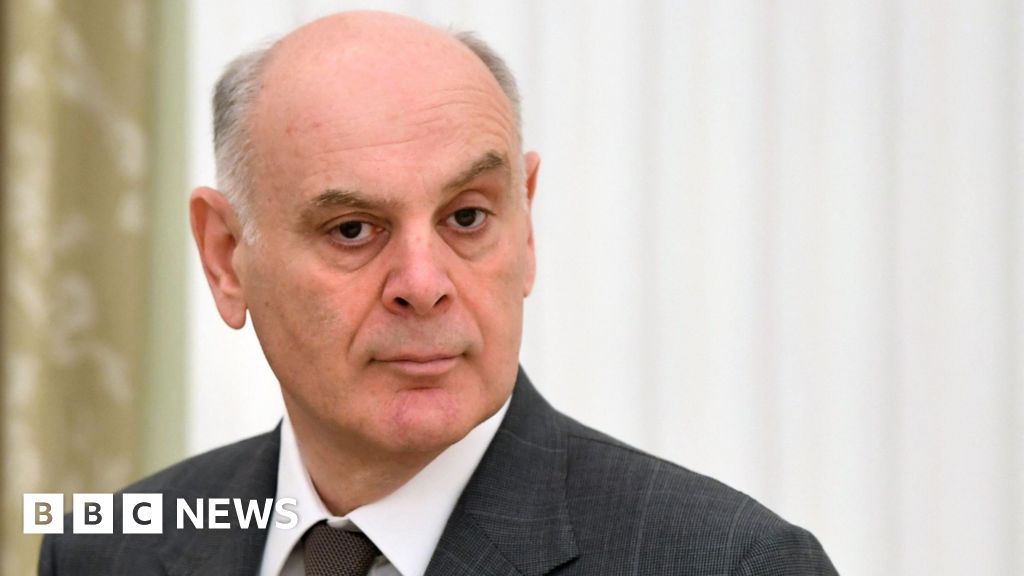

Image source, Getty Images

Image caption,Ukraine’s Interior Minister Denys Monastyrskyy says the situation at the plant is “approaching critical”

The car park is also a place where Ukrainians who manage to make it out of Russian-occupied territories first arrive.

There are queues of cars with people and full suitcases.

Sitting in the shade we meet Olena, who has just made it out of the city of Enerhodar, where the nuclear plant is located.

"It's scary, very scary, there is shelling all the time," she says while bouncing her toddler on her knee.

"There have been many more explosions and it became too dangerous to stay there.

"I didn't want to leave home, but I had no choice."

This car park represents Ukraine controlling what it can.

Unable to force the Russians from Europe's biggest nuclear power plant, the country is instead trying to prepare for the worst, if it happens.

2 years ago

22

2 years ago

22

English (US)

English (US)