ARTICLE AD BOX

By Anna Foster

BBC News, Kyiv, Ukraine

The physical reminders of what happened here will eventually be erased

At the base of a block of flats in Bucha, the sound of sawing echoes around the deserted communal garden.

In one of the doorways a blackened kettle boils on an open fire, blowing clouds of steam into the bitter air. This place should be buzzing with life and sound, with the chatter of children playing and clambering over the climbing frame that dominates the square.

But since the Russians came, everything has changed here. Most people fled, and they're yet to return. There's just one small, hardy group who are trying to pave the way for others to come back.

Sergei and his wife arrived at their flat five days ago. Now they and their neighbours are trying to rebuild their damaged homes, and clearing away the debris of countless Russian shells.

"You always want to come back home", he tells me. "So we used our first chance to return as well. And we used our chance to make sure that all the property is safe, even from locals that might come and steal something."

Sergei takes me to an open grave in the shadow of his building. It's just a few steps away, and we walk in the deep grooves the Russian tanks carved into the mud as they rolled in. Sergei's neighbour - killed as he tried to take a photo of them - lay here.

His name and the date he died are written of a piece of wooden pallet, a rough and temporary gravestone. When Sergei returned home, one of the first things he wanted to do was finally give him a dignified burial.

Not safe yet

In just a few weeks, Bucha locals have become accustomed to death.

Denys Davidoff stayed in the town throughout the occupation. When the Russians left he ventured back onto the streets, and was confronted with a vision of horror. Many people around the world saw photos and videos of bodies lying scattered on the ground in Bucha, some with hands bound behind their backs. But Denys witnessed them himself.

Denys Davidoff saw much of the horror first hand

"When I arrived I saw the street with the dead bodies. I just walked around them, and they were everywhere. I wasn't scared, but it was intense. You got used to it during the month of the occupation."

As the world condemned what it saw, Russia claimed the news was fake, and the bodies were planted after its forces left. But Denys lived through it, and that was not what he saw.

"Some corpses were lying for such a long time that you could see their bodies were covered with the sand and the earth after it rained. At some point I realised I knew some of the people who were killed."

The people of Bucha are still processing the devastation they've lived through. But they aren't entirely safe just yet. More than 3,000 pieces of unexploded ordnance have been found around the Kyiv region so far.

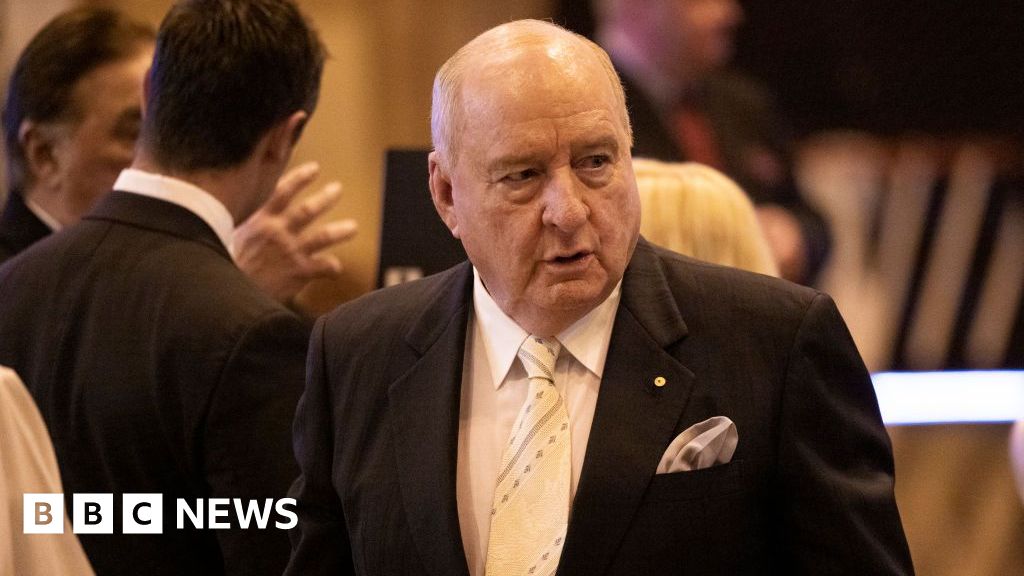

This local man has come back to repair his home

In a nearby village we pass a ditch at the side of the road, with around 20 unexploded shells neatly placed in it, lying side by side. A single thin ribbon of plastic tape runs around the perimeter to protect the unaware from stumbling in.

Making these towns safe again for people to return to will be a huge job.

No silence here

On the road to Bucha, there's an unconventional graveyard. The burned and twisted hulks of Russian military vehicles lie idly by the roadside.

This was a camp, a defensive position, and among the wreckage are signs of the soldiers who once lived here. There are small gold foil pots of food rations, vodka bottles, underwear and socks. Mis-matching camouflage, and a civilian brightly-patterned sleeping bag that someone brought along to keep warm. By the remains of a campfire there's a discarded bottle of shower gel, and someone's toothbrush.

I find pieces of paper with burned edges and Russian script on them. Our local producer Illya scans them and tells me they're from a rulebook for Russian soldiers, a tome of instructions on how to fight and survive. But they didn't here.

Local people pose for selfies among the abandoned Russian equipment

There's no silence in this place. Cars and lorries roll by, slowing down for a better look at the wreckage. Locals arrive in a constant stream, then clamber over the destroyed vehicles and pose for selfies.

Even the single Russian forearm lying in the grass nearby, its flesh and skin charred black, doesn't deter them. A closer inspection reveals that one of the tanks still has a badly burnt body inside - barely recognisable as human. A small group gathers and one man films it on his mobile phone.

In time, this will all be cleared away, and the road will look like it always did. The bodies will be buried, the shattered windows will be mended, and the buildings will be repaired. Eventually the physical reminders of the cruelty that was inflicted will be gone from sight.

But for the people of Bucha, the memories will long remain.

2 years ago

68

2 years ago

68

English (US)

English (US)