ARTICLE AD BOX

By Jonathan Beale

BBC News, eastern Ukraine

This article contains details some readers may find distressing.

Artur describes his job as bringing the dead back from oblivion.

He and Denys, two young Ukrainian men, have the grim task of retrieving the bodies of civilians and soldiers killed in this brutal war. That includes dead Russians as well as their own.

The day we meet them they're in a recently liberated area in eastern Ukraine. Artur says their task is to ensure that no dead body is left behind on the battlefield. The ground is scarred with rubble, abandoned trenches and deep shell holes. They've been told there are several bodies lying somewhere in this scene of apocalyptic devastation.

There's still the sound of fighting in the distance. Artur says they're well aware their job is dangerous, but considers the risks justified "because the most important thing is to take out the dead from this terrible war".

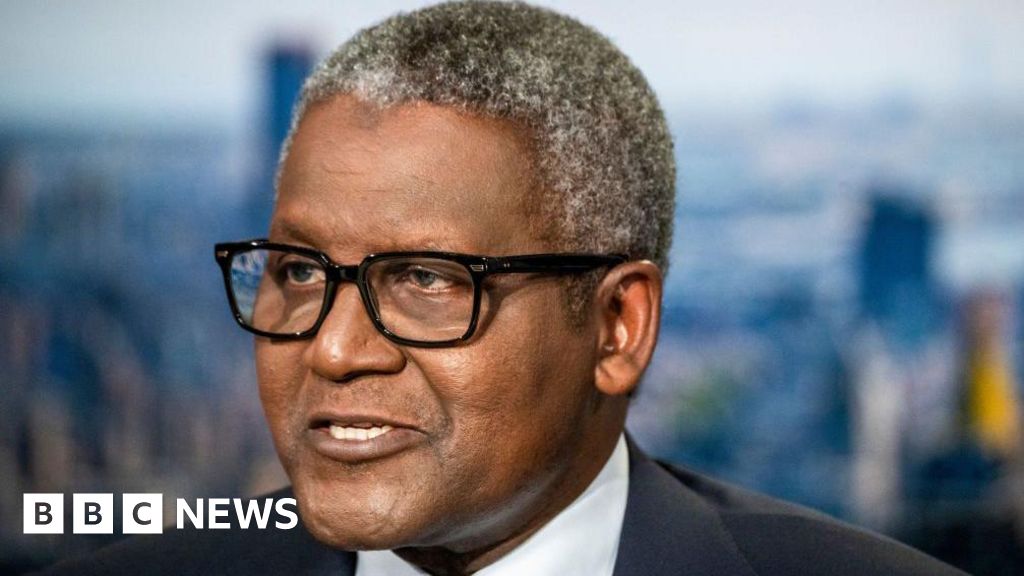

Denys (left) and Artur often attend the funerals of soldiers they've recovered

They open the door of their white van, marked with a red cross and the number 200 - the military code for transporting dead soldiers. There's a sickly smell of death when they open the back door, and the sight of maggots on the floor from bodies retrieved earlier in the day.

Artur and Denys have been told there are several more bodies nearby, but they now have to find the location. Denys launches a small drone fitted with a camera to scout the area. They're not just looking for the bodies, but also for signs of mines. One of their team was recently injured by one. It's a constant hazard.

They now take the precaution of throwing a hook to turn over a dead body before approaching the remains. Russian forces have been known to booby-trap buildings and even bodies before they retreat.

The day before, a Ukrainian military engineer tells me that he thinks there are around 100,000 mines in the recently liberated areas of Eastern Ukraine. It'll take a long time to clear them. The engineer says that, as a rule of thumb, one year of fighting equates to five years of de-mining.

Artur and Denys look for signs of identification alongside the often unrecognisable bodies

After flying the drone for about 20 minutes, Artur and Denys think they've identified a likely location. It's a bombed out building next to a destroyed railway siding. They put their helmets and body armour on and make their way carefully through the rubble.

Inside the collapsed structure there are the charred remains of three bodies. At first it's hard to distinguish the human remains from the burnt-out timbers. Slowly Artur and Denys begin to identify bones. They carefully comb through what's left - looking for any signs of identification.

This time they're not recovering their own but dead Russians. No identification papers survived the inferno, but Artur and Denys find the blackened, burnt buckle of a Russian military belt.

Small pieces of ceramic body armour plates also tell them these three men were fighting for Russia. There are a few other personal items they recover from the ground including a pair of spectacles. Each is photographed and placed to the side. They will be returned along with the human remains - carefully placed into body bags which are then loaded into their truck.

Their van is marked with the number 200 - the military code for body transports

It takes them several hours to complete the delicate task, ensuring every piece of what was once a human life is recovered.

Then the bodies they collect are taken to a local morgue.

Buried with dignity

Artur says he feels an almost spiritual sense of relief when he recovers a body, regardless of who they were.

"We feel grace that the body will finally return from the war," he says.

When they recover Russia's dead he says "there is a clear understanding that they will be exchanged for our deceased and our deceased will be buried with dignity in Ukraine". It's the Red Cross who facilitates the exchanges between countries.

Artur and Denys often attend the funerals of the Ukrainian soldiers they've brought back from oblivion.

They've experienced more death than life over the past year. Artur accepts it will eventually take a toll on their emotional state. But he adds, "I understand that we are doing a good job and this motivates me a little and gives me faith that the war will end soon."

Their role illustrates the war in Ukraine is not just a physical battle. There's a moral component too, reflected in the way an army treats both the living and the dead.

2 years ago

21

2 years ago

21

English (US)

English (US)